No products in the cart.

When the Mountains Were Made

A New Geological Discovery

Story and Photos by Daniel T. Brennan

On Easter of 2016, I sat in the living room with my grandfather, whom we all called Papa, when he unknowingly echoed Stegner’s phrase “the road has always led west.” I had just shared my plan to leave our home in Wisconsin and head to Idaho for graduate school, which had spurred his comment. “If you move west, you won’t move back,” Papa said nonchalantly, and quickly delved into his own story of adventures out West on a road trip as a much younger man. He was that kind of guy, one with a story for every situation—a quality I now realize is likely the hard-earned result of a life well-lived. Between the chaos of family gatherings, Papa would share his stories to those who would listen, usually sitting in his recliner, the one with armrests worn thin from his signature way of slapping his hands when he reached a particularly exciting part, or was upset with the current politics on TV. But Papa (and Wallace Stegner) were right: the West was calling me. The day after I graduated with a bachelor’s degree, my prone-to-overheating little truck was loaded down with gear and the rising sun glinted off the rearview mirror as I headed out to start the first chapter of my own western story.

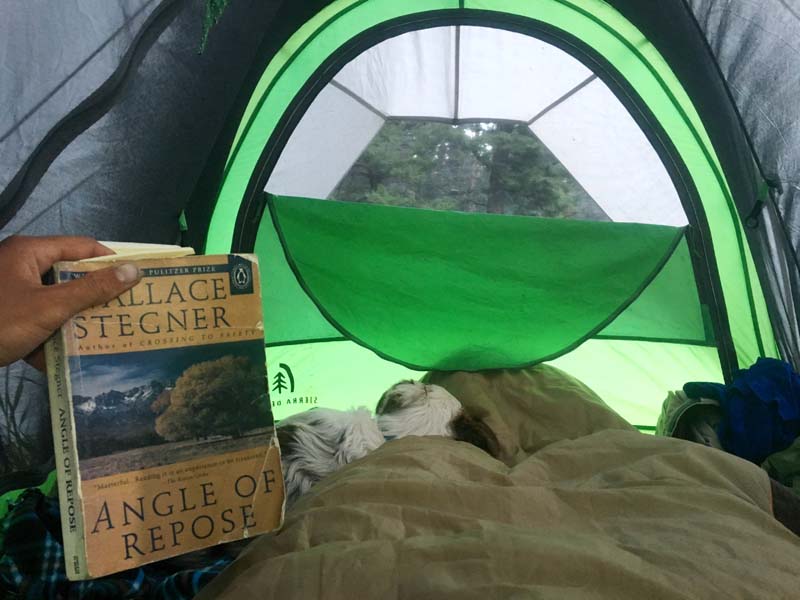

Actually, I had been a full year in Idaho before I was introduced to the writing of the author that Papa had unknowingly echoed. On a visit to my field area in the Salmon River Mountains, one of my professors gave me a tattered secondhand copy of Stegner’s book Angle of Repose, which I read during the cold evenings in camp. To be honest, I spent most of that first year unsure of what I was doing . . . with both my research project and my life. I’m a geologist, and although there is no better place for young geologists to gain experience than Idaho, the billions of years of Earth’s history recorded in the rocks can be daunting to a green scientist. But I knew one thing: I liked to make geologic maps, and under the tutelage of my professors, Idaho was the place to learn. Eventually, as I had hoped, map-making became the main task of my master’s research project, thanks to a bit of funding from the United States Geologic Survey (USGS). I had one summer to complete a geologic map of about a thirty-five-square-mile region in the Salmon River Mountains just west of Challis.

Short of actual hunting or gathering, I think geologic mapping is as close to the activities of our hunter-gather ancestors as a scientist can get. Maybe that’s why most field geologists find something primordially satisfying about it. If you’re not familiar with the premise of geologic mapping, it’s relatively straightforward. Before you begin, you must lace up your hopefully broken-in boots, equip yourself with a topographic map, a rock hammer, a hand lens (which is small magnifying glass for identifying minerals), a notebook, a good compass, and as much food and water as necessary. If you have a trusty field dog, let it out of the truck. (I didn’t have a dog at first, but that changed after a few weeks of isolated hikes, cold toes at night, and one trip “just to look” at dogs for adoption.) With your pack loaded—and the dog you just adopted eagerly leading the way—you start walking. The joke goes that geologic mapping is ninety percent intentional walking, but I don’t think that’s far from the truth.

All joking aside, geologic mapping is a scientifically rigorous activity. As I traverse any mapping area, I constantly develop, test, and alter a 3D conceptual model of the rocks beneath my feet. This geologic model is visualized in my head, sketched in my notebook, and drawn on my map.

The author's battered copy of Wallace Stegner's book.

Bayhorse Lake, Salmon River Mountains.

Blue strikes a pose.

Salmon River Mountains looking east toward Challis.

Dolomite cliffs near Bayhorse in the Salmon River

Mountains.

The author and Blue in the Pioneer Mountains.

In the Salmon River Mountains.

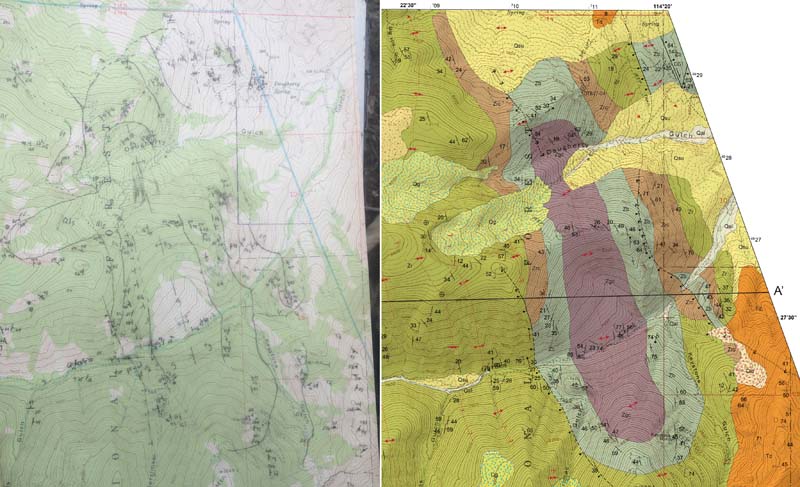

Field map (left) and the finished product.

Idaho State geology class in the pioneers.

Sunset over the Lost River Valley.

In preparation for my Idaho field season, I poured through the literature and found I was far from the first young person who had aimed to find fame and fortune in the craggy peaks and glaciated meadows of the Salmon River Mountains. I uncovered the labor of souls kindred to mine in reading about 18th Century Shoshoni hunters who drove buffalo off the steep cliffs south of Challis, in photos of the still-standing but dilapidated late 19th-Century ruins of failed gold and silver mines at the Bayhorse ghost town, and in several late-1980s publications by a USGS geologist named Warren Hobbs. Although I was fortunate to collaborate with current Idaho Geological Survey mappers, I never got the chance to meet Warren, who died before my time. Luckily, if you’re a young person driving a truck with a university logo in Challis, you open yourself up to some good-natured questioning by the locals. On a particularly warm late-summer afternoon, one provider of such questioning happened to be an old friend of Warren’s. Unfortunately, I did not catch the oldtimer’s name, but with a sparkle in his eye, he made sure the university was not paying for the burger and cold drink I was scarfing down. He said Warren would have been happy to know that young geologists were still out scampering around the Salmon River Mountains, just as he had spent many a summer doing.

As I traversed the field area with my supervisors, we began to decipher something that I’m sure Warren knew all too well. In those mountains, as with most other central Idaho ranges, the original layer-cake stratigraphy of sedimentary rocks that formed in ancient lakes, rivers, and oceans was long gone. The orderly configuration of the sedimentary rocks had been erased and deformed by younger igneous rocks, crystallized from molten material. Adjacent to where these igneous melts had intruded, the pressures and temperatures were great enough to alter the minerals in the rocks that didn’t melt, a process called metamorphism. To muddy the story even more, the rocks had been displaced across a series of faults or fractures, which created a complex three-dimensional pattern. As I have learned in my travels since then, these complexities are not unique to the Salmon River Mountains, but rather are a paradox of many mountain ranges. In such cases, exposure of the ancient earth record comes at a cost: the same processes that can make the rocks available for geologic study can mask their original identity.

I had one summer to figure out what the original configuration was, and decipher the sequence, geometry, and eventually the tectonic forces that resulted in the mangled puzzle in my little region of the mountains. I would have to piece it together one rock description at a time, and I quickly found that the secrets of ancient geologic processes entrusted to these mountains would not be shared easily. After about ten weeks of camping, hiking, eating more hot dogs than I’d like to admit, and of Blue (my newly adopted dog) terrorizing every chipmunk in Custer County, our team arrived at a hypothesis. Our geologic mapping suggested that the original geologic mapping done by Warren and his colleagues had incorporated a slight misunderstanding in how the rocks were configured. They had postulated a large thrust fault or fracture across which rocks were displaced. This supposed structure required that the rocks on top be older and shoved above the allegedly younger rocks they now overlaid. However, our geologic mapping suggested that instead, the rocks on top were indeed younger than those beneath, and there was very little evidence for a thrust fault.

Armed with this hypothesis, we took several kilograms of specifically chosen rock samples to the lab. We prepared the samples in our lab at Idaho State University in Pocatello but for additional analysis, we then traveled to the University of Arizona and shipped other samples off to collaborators in Wyoming, California, and Australia. This analysis consisted of measuring particular isotopes of elements such as uranium and lead in the carefully chosen minerals zircon and baddeleyite. Our results indicated that the majority of rocks thought to be about 450 million years old were actually millions of years older, and had formed mostly between 660 and 600 million years ago. As you can imagine, this was quite an exciting discovery.

The data suggested a new origin for rocks in the Salmon River Mountains. Geologists had already proposed that the shores of an ancient pre-Pacific ocean once ran through what is now Idaho. During that time, Idaho was at the edge of North America, and the majority of rocks that make up Oregon and Washington had not yet formed. The prevailing theory for the rocks we studied in the Salmon River Mountains was that they were deposited on the shores of this wide ancient ocean. However, our data indicated that instead these rocks were deposited when the ocean was just beginning to open. Back then, other continents that were connected to the western margin of North America were in the process of slowly moving, or being rifted, away, which created an ocean. Our discovery showed that this rifting process was taking place in central Idaho more than six hundred million years ago, and this ancient ocean formed in a fashion similar to the creation of better-understood modern oceans such as the North Atlantic. Much later in geological terms, a series of processes deformed the rocks of this ancient ocean shoreline into the Salmon River Mountains we see today. Warren and his colleagues had gotten in some good punches early, and had set us up for the knockout. At last, the mystery of at least some of the rocks in the Salmon River Mountains was solved.

Our uncovering of these geologic secrets would soon give me another reason to continue my westward movement. Papa seemed to have known a thing or two when he predicted that my ticket west would not be a round trip. After two years in Idaho, another geologic challenge led me across an ocean to begin a PhD program in Perth, Australia. Other geologists have suggested that Australia was one of the continents originally west of North America, whose removal might be recorded in the rocks of the Salmon River Mountains. So, I’m now doing research into that question, and although I am now on the other side of the world, geologically, it feels like home.

Unfortunately, Papa is not around anymore to let me know if my westward trajectory is destined to continue after I finish my PhD in a couple of years. But as a good mate of mine likes to say, “Life is all about stories.” Wherever I go, I hope to make a few of my own and find more rocks that reveal stories of Earth’s ancient past. One thing I know: at this point, if I go any farther west, I’ll be headed towards home.

The author encourages anyone interested in studying geosciences to visit Idaho State University at isu.edu/geosciences/undergrad, or get a book on geology from the local library. He recommends Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World, by Marcia Bjornerud.

To learn more about the research Daniel and colleagues conducted, their geologic map can be downloaded at idahogeology.org/product/t-20-01

For their recent scientific paper, visit agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2020TC006145

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only