No products in the cart.

No Forgiveness

A Pioneer Tragedy

By Dan H. Neal

The grandson of a 1911 murder victim in Teton Valley has written a book about the event and its aftermath, No Forgiveness: Family, Polygamy, Murder, and Justice among Idaho’s Pioneering Mormons (WordsWorth Publishing, June 2025). The author, a longtime journalist, describes for IDAHO magazine how he became involved in researching and writing his book, which is followed by an excerpt, reprinted with permission.

I grew up in Idaho Falls in the 1950s and 1960s. We lived on Wadsworth Drive, a neighborhood of twenty-two cinder block homes. Most of the residents were wage-earners. They held jobs at the creamery, in construction, driving trucks or railroading, and teaching in public schools. A mother next door was a florist. My own mother worked seasonally during the spud harvest. One man ran his own barbershop. Several neighbors worked at the Atomic Energy Commission site on the Arco desert.

Many of the Wadsworth homeowners were daughters and sons of Mormon pioneers, my father among them. Dad hung his parents’ wedding portrait on the wall behind the spinet piano on which I practiced nearly every day. Although I didn’t know my grandfather, David Stevens Neal, I did know my grandmother, May Lewis Neal.

I asked my father many times to tell me the story of my grandfather’s murder by Ellington Smith. He knew few details but told me that Smith was tried and convicted, sent to the state penitentiary in Boise, and died in prison. A family reunion on Teton Creek in 1992 sparked my interest in writing a book about the murder. The family gathered in a campground east of Driggs, not far from the Grand Targhee Ski Resort. It is a pleasant site in the forest at the foot of the Tetons, the right kind of place to build a fire and discuss family myths and mysteries.

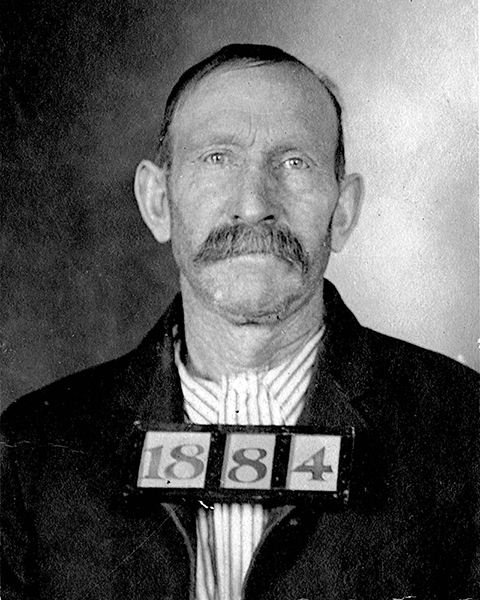

The murder was a taboo topic among Ellington Smith’s descendants until his great-granddaughter Susan Foster began chasing her family genealogy and learned, to her surprise, that Ellington had died in the Idaho State Penitentiary. She obtained penitentiary records that she shared with one of my cousins she knew while growing up in the Teton Valley. The documents opened a window on the past for both the Smith and Neal families. They included an eyewitness account of the killing in a transcript from Ellington Smith’s preliminary hearing, other papers related to the trial, and records made when Smith entered the state pen.

The papers provided no certainty regarding the motivation behind the murder. There were plenty of suggestions. Smith thought my grandfather was stealing his water and plotting to drive him off his farm. One of Smith’s friends told him that my grandfather attempted to manhandle his young daughter.

The Neal family found other explanations in the documents. Our grandfather, who attended the same Darby ward as Smith, was a stalwart member of the community and the principal of the Darby school. He was trusted with the community’s children and believed that his neighbor was mentally unstable and tried to avoid him.

So where was the truth? I went hunting for it first in Darby, where my grandparents had lived on a homestead just across a county road from Smith’s home and farm. A mile north of those farms, the homes of the eyewitnesses still stand opposite the field where the shooting occurred. I read and re-read family letters and papers, then turned to newspapers of the time, archives in Utah, Idaho, and Tennessee, interviews of descendants, and other sources.

My search revealed how deeply the crime affected both families. My grandmother was left with five very young children to support. Smith’s children were effectively orphaned. I also found myself immersed in the Idaho politics that surrounded Smith’s trial, his imprisonment, and his efforts to win a pardon, which continued until his death in 1918.

Ultimately, I found it impossible to determine beyond doubt whether Ellington Smith killed in cold blood, in the grip of insanity, or justly under what attorneys then called “the unwritten law.” I know for certain, however, that a stream of sorrows cascaded over both families.

David Stevens Neal and Carrie May Lewis Neal wedding portrait. Courtesy Neal family.

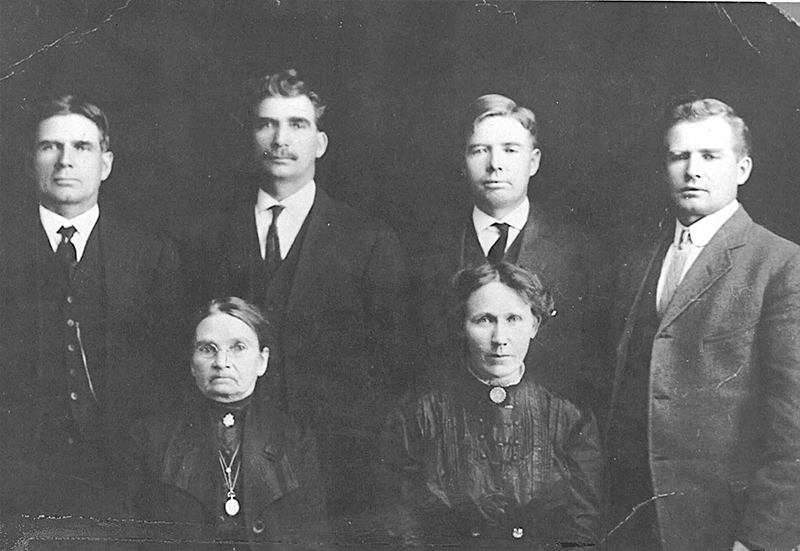

Four of D.S. Neal's brothers, his mother, and his widow. Courtesy Neal family.

Mug shot of Ellington Smith, 1912. Idaho State Archives.

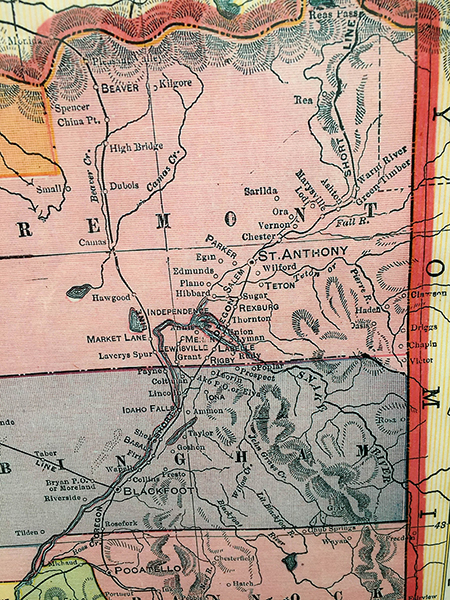

Regional map shows towns extant in the early 20th Century. Idaho State Archives.

D.S. Neal's children shortly after his death, 1911. Courtesy Neal family.

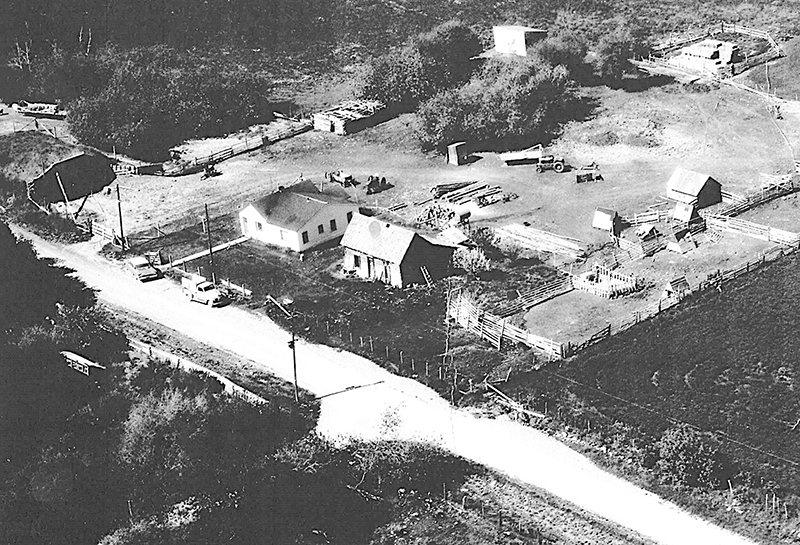

View in 1961 of what was Ellington Smith's property. Courtesy Susan Smith Foster.

CHAPTER ONE

Murder on a Still Morning

On the morning of July 5, 1911, David S. Neal left his house south of Sorensen Creek in Idaho’s Teton Valley to irrigate the field he had rented from Charles Christensen. He had milked his cows and put them out to pasture, then ate the breakfast cooked by his wife May. Their five young children were asleep in their beds after celebrating Independence Day in town the day before.

Dave and May talked about their good time in Driggs enjoying the parade and fireworks. Most of the valley’s residents took the day off to celebrate America’s independence. The Neals had bumped into their good friends, Alma Hansen and his family. Hansen, like Dave, taught in a rural public school and was a farmer. They had a lot to talk about. Top of mind for Dave was his neighbor Ellington Smith. The two had been feuding. Neal considered Smith mentally unstable.

When Dave left May after breakfast, he picked up his shovel and walked around the north side of their house, hoping to avoid running into Smith. He walked the mile north to Christensen’s field and began working.

The valley, known then as the Teton Basin, sparkled in the early morning. Dave was taking water that flowed out of Darby canyon, one of the many drainages that slide down into the valley from the divide created by the Teton Range, which separates the north and south forks of the Snake River. By early July the spring torrents had subsided, beginning to fade like the lilac blooms that had scented the air a few weeks before. It was a glorious morning, windless and the air fresh from the night’s cooling.

By 9 a.m. the day’s heat had begun and Neal was diverting water into the field.

The basin was dotted with small farms, nearly all of them owned by pioneering Mormons. As Neal managed the water, he could see that Octavus “Tave” Smith, Ellington’s nephew, had started on his morning chores in his own farmyard across the road.

Tave had left his sleeping family in the house and saw Neal as he walked to his barn. His chores took time. Tave milked his cows, turned his horses out of the barn, then returned to his house and joined his wife Ellen. She placed bowls of oatmeal before her young sisters Ida and Essie, and her two young children. Tave offered a short blessing over the breakfast. They agreed that Essie would help Tave weed the garden behind the house, but first he had to tend to an irrigation stream running in his own field. Tave and Essie walked outside. Essie, just thirteen, went to the vegetable garden, and kneeled to pull weeds from the rows of carrots.

A mile south, sometime just before 10 o’clock, Ellington Smith mounted his bay horse in his yard across the county road from Neal’s place. He brought his rifle, a Winchester Model 86, a repeater. The hills surrounding the valley were full of wildlife, not in the same numbers seen by the earliest settlers and the natives who preceded them, but there just the same. The gun chambered a .40-82 cartridge used to kill large game animals like elk. The black powder cartridge imparted higher velocity to the large, 260 grain bullet than others of its day, making it easier to shoot accurately. Smith had no plans to shoot elk.

Smith rode the mile north to the road’s end at its intersection with the Darby Canyon Road, which runs west from the mouth of Darby canyon. The Darby Canyon Road separated Christensen’s field on the north, where Neal was irrigating, from the homes of Smith and Harvey Loveland to the south. Tave’s house, garden, and fruit trees were planted along the southwest corner of the intersection. Harvey and his brother Oscar lived in a house fifty yards east of Tave’s place.

When his uncle rode up, Tave was hoeing carrots in his garden. Essie weeded, working on her knees. Ellington greeted him.

“Good morning.”

“Morning, Ton.” He stopped hoeing.

“Lot of weeds.”

“Well, it’s that time of year.”

Ellington slid down from his saddle and tied the horse to the corner of Tave’s pole fence. Taking his rifle with him, Smith crossed the Darby Canyon Road, climbed a fence and stepped into Christensen’s field. Octave watched him. Must have seen a coyote, Tave thought. He’ll shoot it.

His uncle had not seen a coyote. Ellington strode out into the field and walked within shouting distance of Neal. It was a still day but Neal, intent on his irrigation, had not seen or heard him.

“Neal, you son-of-a-bitch. Why’d you steal my water?”

Neal turned to him. “I never stole any water. I took my own water.”

Smith raised the rifle, sighted down the barrel, and pulled the trigger. The sound of the blast reached Neal with the bullet. It smashed into his left shoulder, dropping him.

In his vegetable garden, Tave stepped toward Essie. “He shot Mr. Neal.”

Essie began crying and started for the house. Tave stopped her.

Tave stood with his hoe in hand. He watched as his uncle, unsure or unsatisfied, walked closer to Neal, raised the gun and fired a second time, putting the bullet into Neal’s head. Tave looked away.

Now certain that he had killed his neighbor, Ton Smith walked back to the fence, crossed it, then crossed the Darby Canyon Road and untied his horse from his nephew’s fence. He said nothing to Tave and nothing to Essie but swung up into the saddle and turned his horse west, riding slowly away from his nephew and past the dead man down in the ditch.

Octave’s wife came rushing around the house.

“Tave! Essie, come in with me and Ida.” Essie ran to her and they went into the house. Tave instead turned away. Getting his horses into the barn somehow made sense in the moment. He grabbed their halters, put them in, and only then returned to the house and the women huddled inside.

Oscar Loveland appeared at their door. He knocked and pushed it open. Oscar and his brother Harvey had heard the shots and stepped out on their own porch to see Ton leave the field and ride away. “He wasn’t in no hurry,” Oscar observed.

They agreed that the constable must be informed. Someone had to tell May Neal. Oscar walked back to his own place and conferred with Harvey. A few moments later Tave saw Oscar set off down the road the killer had ridden up. He had a mile-long walk to figure out how to deliver the news to a woman who did not know she was a widow.

Harvey went the other way, crossing into Christensen’s field and walking toward Neal. He pulled the dead man out of the ditch—it seemed the right thing to do—and slowly walked back to his porch. Time slowed. Octave waited a few minutes, then called from his porch to his neighbor. They should go cover the body. Tave went to his barn and found a canvas, met Harvey in the road and they walked to the dead man. They saw that the wounds bled and the blood slowly seeped into the dirt. Tave straightened Neal’s arms and Harvey helped spread the canvas over him. No wind. It would stay in place. They walked back to their houses. One of them had to go find Constable Eddington.

After shooting Neal, Smith rode on west, walking his horse. He was not done with his killing. He expected to find A.C. Larsen, another Darby ward member, a good friend of Neal. Andrew Larsen, Smith believed, had conspired with Neal to harass him into selling his farm. The water theft, the threats Neal shouted at him, and other unmentionable, unthinkable insults were part of their twisted strategy. He knew Andrew Larsen used the Darby Canyon Road when he returned home from his trips to Driggs. He would run into him there or down on the main road connecting Driggs to Victor.

But Larsen got lucky that day. He chose a different route home and Smith did not find him.

Ellington turned the bay. He knew his fate. Deputy Pickett or the constable would find him and take him to St. Anthony and the county jail. Confident in his justification, he did not fear arrest.

He rode to Ezra Plummer’s place. Plummer stepped out as Smith reached his porch.

“Neal is layin’ up dead in the ditch in Charley Christensen’s field,” Smith said, looking down from his horse.

Plummer could not turn his eyes from Smith’s strange, piercing gaze. He saw the rifle lying across the saddle below the horn.

“I guess he won’t steal any more water,” Smith muttered.

Plummer pondered the description of the school teacher dead on the ground. Murdered.

“Can I cut across your fields there to get back to my place?”

“No, Ton. I can’t let you do that,” Plummer paused. “I can’t help you now.”

Smith looked at Plummer. They had known each other a long time. He turned his horse and walked it back to the road. Then he rode the old horse home. He found a way around to avoid going back past Christensen’s field and the people he knew would be gathering there, waiting for a wagon to carry the dead man’s body into Driggs. He reached his house and looked across the road to the Neal place. No one was in their yard and no one was at his own house. He remembered that his daughter Mabel, young, lovely Mabel, was with friends in Victor. He put the horse away and walked back to his porch. He propped the rifle near the door. He went into the house and waited for the constable.

He did not wait long.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only