No products in the cart.

Medimont—Spotlight City

A Long-Ago Dream Drowned

By Mary Terra-Berns

I was making good time on my morning bike ride from Rose Lake to Harrison on the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes. Other than waterfowl, I had the trail to myself. I glided through Medimont and onto the diked section that separates Cave Lake from the wetland and the Coeur d’Alene River on the other side. On the far side of the dike is a small grove of trees and shrubs I refer to as the “tree tunnel.” It’s a quiet, shady, cool spot that typically harbors a loafing moose or two in the shrubs a few feet off the trail.

On this day, however, it wasn’t a moose or two. It was four young bulls roughhousing near the opening to the tree tunnel. My cadence slowed and then came to an abrupt halt when one of the bulls stopped goofing around and directed his attention towards me. The others joined the stare-down and blocked the trail with an intimidating wall of moose. This definitely busted my trail ride tempo. After a few minutes I realized my options were limited, actually nil, for getting past the moose wall, so I turned around and made my way back to the picnic table at the Medimont trail access site.

I pulled a snack out of the pocket of my jersey and settled in for what I hoped wouldn’t be a prolonged delay. Sitting on the picnic table in front of Medicine Mountain and next to Cave Lake, I looked over at the yellow Medimont Mercantile, which has been renovated and is now a private residence. The bottom floor has a sitting area, a bar-like counter, and memorabilia, including an old cash register from around the end of the 1890s. As I sat in the sun enjoying mixed nuts and dark chocolate, I pondered the history of Medimont.

In 1880, about eleven years before Medimont (a name derived from Medicine Mountain) was established, Captain Peder C. Sorenson, commander of the Amelia Wheaton steamer, was traveling up the Coeur d’Alene River when an interesting feature came into view in the distance. He called it Green Island, because it appeared to be surrounded by water and green meadows. Captain Sorenson had come from Norway to Fort Coeur d’Alene (later Fort Sherman) in 1879 to build the Amelia Wheaton. As the lake’s first captain, he named the bays, points, and other features.

A short time after this, a Catholic missionary named Father Goosie from Hangman Mission near Plummer informed Captain Sorenson that Green Island already had a name. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe called it Smaq’wqn (English spelling, Smokokum), which means “Medicine Mountain.”

According to Franz Boas and James Teit in their book, Coeur d’Alene, Flathead and Okanogan Indians, three to four thousand Coeur d’Alene tribal members lived in eleven winter camps dispersed along the Coeur d’Alene River from its mouth at Harrison to the Old Mission at Cataldo. The book—which actually was the 1927-‘28 annual report to the Bureau of American Ethnology, published by the Smithsonian Institution—said these camps were considered permanent wintering places before the tribe was decimated by smallpox epidemics around 1832 and again in about 1850. Every camp along the Coeur d’Alene River lost members to the disease and some camps were almost completely wiped out. A 1905 report from the U.S. Indian Department gives the number of Coeur d’Alene tribal members as 494, all of them living on the reservation.

One of the camps, known as Sma’qEqEn to tribal members, was located where the town of Medimont is today. In his book, A Brief History of the Coeur d’Alene Indians 1806-1909, Jerome Peltier indicates that in the early days the family of Chief Morris Antelope (1864-1941), could be found around Medimont. Chief Antelope or Ats’qhule’khw, which means “Looks at the Land,” was a strong advocate for the tribe when it started following the missionaries and began settling into a life of farming and ranching on the reservation. The tribe’s current leader, Chief James Allan, is the great-great-grandson of Chief Antelope.

According to The Idaho Encyclopedia, compiled by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, the native name Smaq’wqn translates as “Bodies Lying on the Mount.” Tribal members came here to convalesce from their illness and, with the guidance of a medicine man, they used herbs and roots found on the mountain to cure what ailed them. Many of the Coeur d’Alene tribal members who were not cured and died of smallpox were reportedly buried in this area.

Tree tunnel at Medimont.

Young bull moose confront each other and block the way. Mary Terra-Berns.

The former store at Medimont, now a private residence. Mary Terra-Berns.

The former Medimont Hotel, 1925. Museum of North Idaho.

Contemporary homes at Medimont Mountain. Mary Terra-Berns.

Cave Lake at Medimont. Mary Terra-Berns.

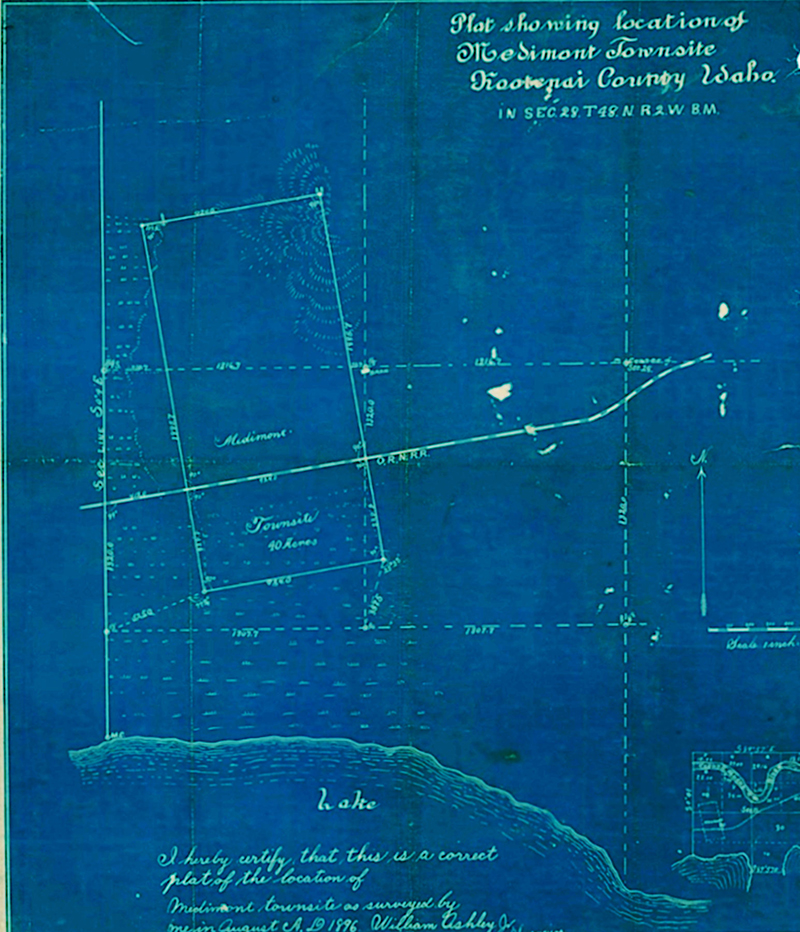

The city plat from 1896. Mary Terra-Berns.

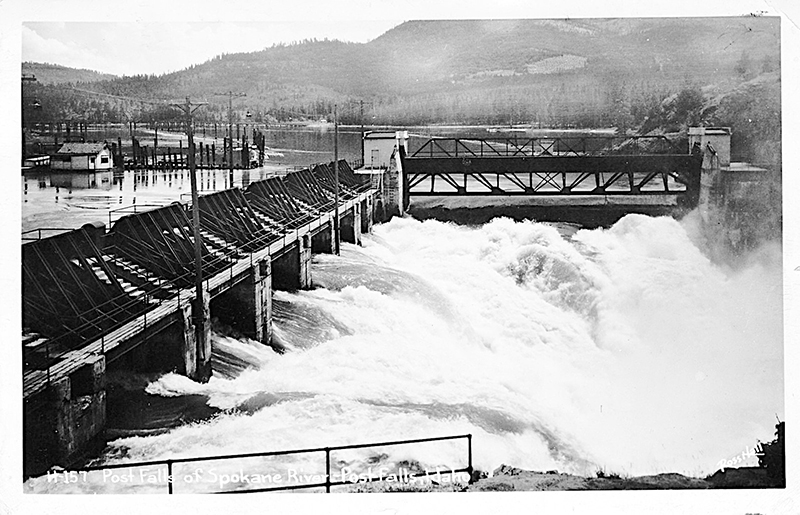

Post Falls Dam North, 1950. Water Archives, CC By-2.0.

The WWP powerhouse, built in 1906. Mary Terra-Berns.

The old Indian Springs School, 2013. . Nancy Reilly Young, CC By-2.0.

An article in the April 21, 1911 edition of the Camas Prairie Chronicle in Cottonwood that was taken from the Harrison Searchlight newspaper seems to support this notion: “While digging postholes on his place at Medimont, Simon Moe dug up the skeleton of an Indian. Around the neck was a buckskin string attached to a rawhide buckskin sack that held fifty well- preserved elk teeth, some as fine as ever seen anywhere. Years ago the place was an Indian burying ground.”

Several years earlier, about 1887, a rail line from Plummer to Wallace had been constructed by the Oregon Washington Railroad & Navigation Company to connect the new mining district, today’s Silver Valley, to the main line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. In 1889, shortly after the establishment of this Wallace Branch, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe signed a treaty that was ratified by Congress in February 1891, which ceded the northern and eastern portions of their reservation to the government. That land had been opened up to settlers in 1890.

Numerous towns sprang up along the rail line and Coeur d’Alene River as emigrants arrived in the valley and found abundant farming and grazing land to homestead. Mill towns provided lumber for the mines and for an increasing number of homes, barns, and other outbuildings that began to dot the valley along the river.

Titus Blessing and Jonathan Mauk homesteaded next to Cave Lake on the newly opened land. The register and receiver of the Coeur d’Alene Land Office got a submission from another settler, James W. Slayter, for an eighty-acre tract that included the townsite of Medimont. But those acres were on property being homesteaded by Blessing and Mauk. Slayter and the rest of the townsite supporters contested the two men’s homestead entries, which caused a lengthy legal battle. The disagreement was taken to the Coeur d’Alene Land Office and the U.S. Department of the Interior, where it was decided that approximately twenty acres would go to the townsite and the remaining acres to Blessing and Mauk, which was endorsed by the townsite supporters.

Slayter opened a general store in 1891 and established a post office (which closed in 1963) in the store. Slayter’s post office application was granted under the name Medimont, and he was designated postmaster. Joseph Moe, one of Simon Moe’s brothers, built a three-story hotel which, according to an advertisement in the May 14, 1892 issue of the Coeur d’Alene Press, provided “clean beds, good table and boats for guests to use free of charge.” Guests could enjoy fishing at any time of the year and waterfowl hunting during the fall on the 750-acre Cave Lake. After a day of leisure and outdoor activity, the “first class” hotel bar offered cocktails.

An Illustrated History of North Idaho: Embracing Nez Perces [sic], Idaho, Latah, Kootenai and Shoshone Counties, State of Idaho, (1903, reprinted by Forgotten Books, 2018), describes Kootenai County as a paradise for hunters, fishermen, and tourists. The new entrepreneurs anticipated Medimont would become a well-known and highly popular resort destination in northern Idaho. Articles promoting the new resort, such as one in the Coeur d’Alene Press from April 1892, proclaim, “The cave from which the lake derives its name, while not so large as the Mammoth Cave of Kentucky, may be penetrated for a distance of two hundred feet and is no less wonderful than caves of a great deal more notoriety.” An exaggeration, but a nice promotion for the new resort town.

Both Slayter and Moe took on partners as business amplified. The Slater & Evans General Store specialized in sporting goods but also stocked groceries, dry goods, and hardware. Robert Short joined his brother-in-law at the motel and regularly renewed the liquor license for the bar. Short was a tall, heavyset man that The Silver Blade newspaper of Rathdrum referred to as “the Bill Nye of Medimont.” Obviously not Bill Nye the Science Guy whom we know today, but Bill Nye the humorist and author from the late-1800s.

As word got out, Medimont became the location for pleasure trips and events. Many people from Harrison regularly boarded one of the steamers that traveled up the river to spend a day or two at the resort. Occasionally, large groups would charter a steamer to take them up the river to attend parties, dances and other functions put on by the town of Medimont. Not wanting to be left out of the festivities, many excursionists came downriver from Wallace, Gem, Burke, and Kellogg to join in.

Although Titus Blessing was a farmer, he also had a musical side hustle. A brief note in the April 23, 1892, issue of the Coeur d’Alene Press remarks, “Mr. Blessing returned from Spokane yesterday, bringing with him a fine piano, the first one in the town.” He may have played, along with other musicians, at the town’s many dances and other events. One of the regular “Medimont News” columns in the Coeur d’Alene Press, this one from April 16, 1892, endorses the new resort: “Joe Moe gave a dance Saturday night, which was largely attended and was pronounced a social success. Joe knows his business when it comes to entertaining his friends.” In 1892, the town was hopping.

During the following winter of 1893-94, heavy snows piled up in the mountains and stayed through the cold spring months. When the heat of summer finally arrived, water came gushing out of the highlands into the streams and lakes, which quickly inundated meadows and fields, as well as towns throughout the valley, in three to four feet of water.

The people of Medimont claimed the flooding was due in part to the dam at Post Falls. The twenty-foot-high diversion dam had been built on the northern channel in the early 1870s by Frederick Post, whose namesake is Post Falls, to power his gristmill and sawmill. Medimont’s citizens wanted the dam removed and the river channel lowered. It was an improbable entreaty.

In 1902, the sawmill burned down and Post sold the site to Washington Water Power (WWP, now Avista). WWP constructed dams across each of the three channels in 1906, which caused the water level behind the dams to rise by twelve feet. Amelia Schaeffer, Titus Blessing’s eldest daughter, had something to say about this is an interview for The River of Green and Gold: A Pristine Wilderness Dramatically Affected by Man’s Discovery of Gold, a 1974 report written for the Idaho Research Foundation, Inc. Amelia told authors Fred W. Rabe and David C. Flaherty about people she described as squatters who were “threatening to blow up the Post Falls Dam after water inundated their land, but a lawyer in the vicinity, after hearing their plans, talked them out of it.” Hans Dierks, a resident of Lane, a couple of miles upriver from Medimont, was interviewed also. He commented, “And to think we could have bought out Frederick Post for a mere one hundred and fifty dollars.”

The high water inundated the river valley all the way to the Old Mission at Cataldo, which is about eighteen miles from Medimont by road today. To add insult to injury, this high water was infiltrated with sewage and heavy metals that had flowed downstream from homes and mines in the Silver Valley. Toxic water spread from one side of the valley to the other, covering fields and pastures, and swamping homes from Harrison to Cataldo. Even after the floodwaters receded, small streams and channels that flowed from the river into the lateral lakes continued to contaminate the water and soil. One of these small streams flowed into Medicine Lake, which is connected to Cave Lake by a short channel. High water during the spring months continued to swell the streams and river, which added yet more toxic water to the lakes and surrounding soil.

As the water receded, these toxic ingredients covered the ground and permeated the soil. Grasses and other vegetation absorbed the lead, zinc, and other toxins. Around 1900, farmers in the valley began to notice this lead pollution from the mines. Hans Dierks recalled, “They tried to dike the lead water out but it didn’t work.”

WWP and the Mining Association compensated the affected land owners but according to Amelia Schaeffer these were “piddling payments for easements on their lands.” She owned three hundred acres along the river that her father had left her but most of the other homesteaders moved on. She said, “Most of the other squatters forfeited their land because they failed to pay back taxes.” One assumes they didn’t want to pay taxes on toxic land.

Waterfowl and other animals were exposed to large amounts of heavy metals when they grazed in the mudflats and meadows, which eventually killed many of them. Even with improved conditions today, swans and Canada geese succumb each spring to lead poisoning from foraging on contaminated vegetation. Efforts are being made to remedy this situation, but cleanup will take time.

Fish also began to disappear from the toxic aquatic environment. In The River of Green and Gold, the authors mention, “In the 1890s, when excursion boats went up the river, scraps were thrown to the fish that were observed by the thousands in the big eddy below the Old Mission. In fact, trout were featured on the dinner menu aboard the steamers.” However, in the early 1900s, local residents noticed fewer and fewer fish in their creels. In 1932, Dr. M.M. Ellis of the United States Bureau of Fisheries conducted a study of the South Fork and main stem of the Coeur d’Alene River. As he described it, “Mine wastes poured in the South Fork in the Wallace–Kellogg area have reduced the fifty miles of the South Fork and main Coeur d’Alene River from above Wallace to the mouth of the river near Harrison to a barren stream practically without fish fauna, fish food, or plankton.”

Although some fish could be found in the lateral lakes, the catch had diminished. This new reality did not bode well for the little town with big plans to become northern Idaho’s premier resort. Even though flooding continued to occur regularly, Medimont persisted for a few more years. However, the double whammy of substantially elevated water levels and toxic sludge likely fast-tracked the demise of the resort community.

Town plats from 1896 and 1903 show the lakeshore a short distance from the nearest townsite lots and the rail line that went through town. A 1925 photo of the Medimont Hotel appears to show the shore of Cave Lake next to the rail line. The current property boundaries delineated by the Kootenai County Assessor’s Office show the same lots under water and the lake next to the old rail line, now the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes. It appears that these lots were lost to the elevated water levels from the Post Falls Dam.

In 1903, Medimont had about seventy-five permanent residents, down from a couple hundred a few years earlier. The town’s dreams of becoming a favored northern Idaho resort had drowned. Nowadays, the unincorporated community has about fifty residents.

James Slayter died in 1911 from a burst appendix. His wife, Myrtle, remarried a couple of years later and continued as the postmistress until around 1920, when she moved with her new husband to Coeur d’Alene. My friend and history buff, Woody McEvers, shared some information he found on Joseph Moe. He was listed on the 1910 census as a policeman in Harrison but by the time the 1920 census rolled around he was listed as a farmer. Woody found Homestead Certificate #1471, from 1906, signed by President Theodore Roosevelt, which granted Joseph Moe 171 acres on the east side of Medicine Lake. That land is still owned by his descendants. Titus Blessing lived into his eighties and is buried in the Medimont Cemetery.

As I sat on that picnic table in Medimont a while back, trying to imagine the place in the late-1800s, I had a hard time visualizing it as a merrymaking destination. I never was able to find a picture of the town from those days, and couldn’t figure out exactly where the hotel was located. If I had to guess, I would say it was directly across the bike trail from where I was sitting that day. Medimont is a peaceful place and I imagine its few contemporary residents are happy to leave the dream of a party town in the past.

I finished my snack and hopped off the picnic table, eager to check on the king-of-the-trail activity. With any luck, a king had been crowned and playtime was over, which would let me continue my ride. Unfortunately, they were still jostling with each other, each claiming the trail as its own. Teenage bull moose can be unpredictable. It didn’t seem wise to challenge thousands of pounds of big feisty animals. I flipped the bike around and headed in the other direction.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only