No products in the cart.

We Already Did It

A Day on the Set of Stockton to Table Rock

By Bradley Elliot Norton

We’ve made our days. We know that, and knowing that, we should expect that. Yes, today is busier than most. But we planned it that way, and we always follow plans…or the plans follow themselves.

It’s July 16, 2022—Day Six in the production of Stockton to Table Rock. The charter school we’ve rented sits on the western side of Meridian where suburban developments lie uneasily beside empty fields and dry drainage canals. A two-story building just north of the interstate, the charter school is small for what it’s acting as (a Boise public high school), but at an angle, dawn’s brightening hues give it a shape and depth that make it seem larger than it is.

Zoë Kelly and I enter the parking lot at 7 a.m. As usual, I’m driving, and Zoë is in the front seat looking over the script. She uses her thighs to prop up a white binder, resting her bare feet against the dashboard and making slow smacking sounds as she moves a mint around her opened mouth. She’s a twenty-nine-year-old playing an eighteen-year-old, and lately I’ve noticed she has adopted the vocal cadences and gestures of a teenager. No matter. She’s the head of the production. The lead actor, the line producer, the person who orders lunch and then performs a two-page monologue. She’s also my wife.

“That’s so annoying,” I say.

“What?” she says.

“Can you close your mouth when you’re doing that?”

“Doing what?”

“Doing whatever you’re doing with your mint. I’m trying to think.”

Our car passes into the shadow of the building. She stares at me as I park.

“Sorry.”

“It’s okay,” she says. “Wait, though, I’m confused. You don’t like this noise?” She hits the mint against her teeth. “Or is it this one?” She makes a perfect O with her mouth and slurps.

“Shut up,” I say, chuckling.

I’m a little lightheaded and my eyes are strained from lack of sleep. This is our sixth fourteen-hour day in a row and last night I stayed up watching the dailies with our cinematographer, Danny Klamerus. The production’s margins have been razor thin. We don’t have a lot of money and we can barely cover location rental and food. Each shooting day is a sprint. Adjusting angles. Eliminating angles. Simplifying blocking. Telling actors they only have one take.

But in spite of all this, we’re making a real movie. Not some trifle. Not something that requires asterisks. The first week of footage has the sheen of real professionalism, and after watching it, I’m now convinced it’ll play in theaters to actual strangers—not the good-natured friends and family who have spent ten years watching my movies with half-glazed eyes and constipated smiles. The lighting is evocative. The camera moves are captivating. The acting is nuanced. The script is hitting all the beats. We’re doing it.

Director Bradley Elliot Norton and director of photography Daniel Klamerus. Mia Miller.

Zoë Kelly (left) and associate producer Paige

Harwood on the set. Wyatt Llewellyn.

Zoë as Rori. LowerGentry Studios.

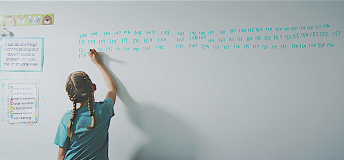

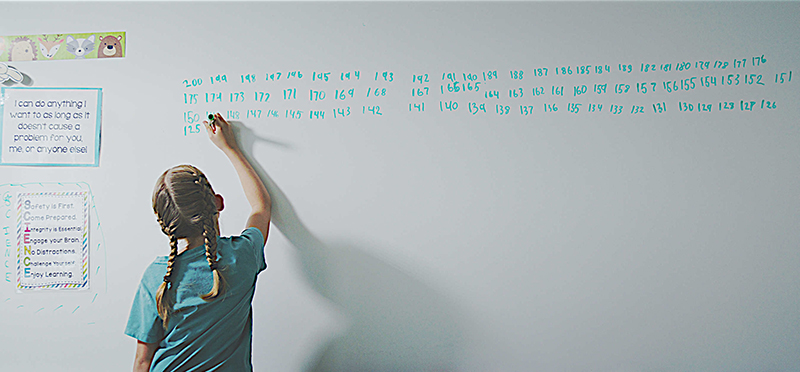

Melia as the young Rori at school. LowerGentry Studios.

Melia Kane and Jessica Ires Morris in a scene. LowerGentry Studios.

Jessica plays Rori's mother. LowerGentry Studios.

Gabrielle Lenberg as Hailey. LowerGentry Studios.

Zoë during a break. Daniel Klamerus.

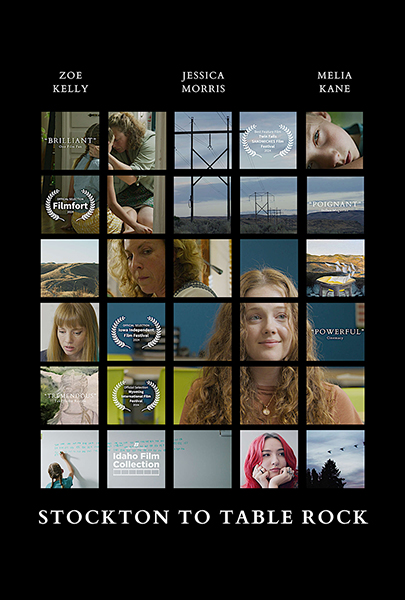

Poster of the film. LowerGentry Studios.

“You ready?” Zoë asks as she’s about to exit the car.

“Yeah…yeah…the big day. Thirty extras. Seven scenes. Wrapped by nine.”

“Wrapped by nine,” Zoë echoes.

Sprinklers mist the manzanita shrubs along the front of the building. We’re in the middle of a heat wave and even in the early morning the air feels close, claustrophobic. In the drop-off zone, Danny unloads plastic cases and white wooden boxes. Beside him, my brother, co-producer, and sound designer, Chuck Norton, holds a four-foot flag—a framed piece of black canvas that deepens the dark side of an actor’s face.

“What do you want me to do with this?” he asks Danny.

“Inside,” Danny says.

Zoë and I each take a box and follow Chuck into the school. It’s already abuzz. Voices echo through the hallways. Sneakers chirp on the linoleum. Immediately on the other side of the double doors, Chance Fuerstinger (assistant director and associate producer) has set up a welcome table, his curly hair moving slightly in the sterile, cool breeze of an A/C vent. He has a stack of maps showing craft services, bathrooms, and where each scene will be filmed.

“What time will Marc be here?” I ask him.

“He shows up with the extras,” Chance says.

“Nine?”

“Nine,” Chance says. “Oh, and good morning.”

“Sorry. Sorry. Good morning, Chance.”

Deeper in the school, associate producers Paige Harwood, Joseph Rodman, and Wyatt Llewellyn are setting up a prop and costume area in one of the unused classrooms.

“Everyone got here early,” I say to Zoë.

The first thing on the schedule is scene four—very simple and short. Rori, played by Zoë, is dropped off late while Rori’s girlfriend, Hailey, waits outside. The action is straightforward and in the finished film the scene will run forty seconds. But right before filming, I’ve become concerned we don’t have enough time for five shots.

“Maybe it’s overkill. We might not need five,” I say to Danny and Chuck. We’re now waiting outside for the actresses to finish wardrobe and makeup. Danny’s camera rig rests on the asphalt and he stands with his hands behind his head. Chuck leans against his boom mic like it’s a staff. It’s getting hotter and a line of sweat drops from my armpit down my ribcage as I stare nervously at the sky.

We need to be done with the scene before the sun crests over the east side of the building and ruins the exposure. “Crappy daylight” (as Danny calls it) is the number one telltale of a low-budget movie and so far we’ve been able to avoid it. Major productions can shoot during the afternoon, but they have flags the size of football fields and lights bright enough to compete with the sun. We, on the other hand, don’t have that kind of equipment or the personnel to man it.

With my walkie talkie I ask Chance how long the actors will be. He says two minutes, but miraculously they’re out in thirty seconds.

Zoë and Gabby Lenberg (who plays Hailey) wear Gen-Z staples: baggy jeans and asymmetrical crop tops. Jessica Morris (who plays Rori’s mother) wears her character’s work uniform: a green T-shirt with striped sleeves that would work as a bartender’s blouse or a soccer player’s jersey.

“We’ll get through today,” I say to Zoë before the first take.

“We already did,” she says. “We just get to experience it.”

This has been a mantra for both of us the entire shoot. Every film production is blessed and cursed. Good fortune following bad luck following good fortune…constant deposits and withdrawals on karma and the hope of a positive balance after nineteen days. When doing something that stretches you in every possible dimension—creatively, organizationally, physically, monetarily—it’s best to think of the world as deterministic. Whatever’s going to happen is going to happen. We’re all lucky enough to find out what that is.

The first angle is easy. A wide shot of the car approaching the entrance. The lens centers on the corner of the front façade—the shadow of the building looming frame-right and the slowly ascending sun on the left. The car enters and drives through the parking lot. Each take requires a lengthy reset (me on the walkie talkie saying “a little slower this time, please”) so we only get two takes before moving on.

I keep notecards for every shot in my breast pocket. I take them out and look at the second setup. It’s a rather complicated tracking move that would require Danny to run alongside the car with the steadicam. Because cars add time between each take, I look at Danny and Chuck.

“Do we actually need it?” Chuck asks.

Danny is looking at the sun while I try to play the edit in my head.

“No,” I eventually say and tear up the notecard. It feels freeing, and I look at the three shots that will compose the rest of the sequence.

Somehow, it’s already 9 a.m. We’re behind, but not too bad. Extras have begun to arrive, and Chance and Joe are directing them away from our sightlines and ushering them into the building between takes. We’re working on another stationary shot but this one is much closer. Hailey sits on the front bench. The car comes into the foreground, Rori exits the car, the car drives away, and finally Rori and Hailey enter the school. That’s it. In the finished film, the shot will be intercut with two others, so the only things we absolutely need (“absolutely need”, I say when I’m explaining it to the actors) are the beginning and the end.

We quickly rehearse Hailey and Rori’s movement and do the first take. Doesn’t work. The car needs to stop in a precise spot.

“Line your head up with this pillar,” Chuck says to Jessica.

We get it in the second take and then we’re quickly inside the car. From the backseat, Danny, Chuck, and I cover the same movement, this time with a little dialogue between Rori and her mother. The shot is, again, simple. No racking focus. No pans or tilts. The three of us snuggle in the backseat.

“Can you move over, Bradley?” Chuck says to me as he tries to get a good vantage point with his boom mic. “A little closer to the door, a little closer, that’s good.”

I’ve become dimly aware of two things. The first is a group of construction workers who have begun amassing at the far end of the parking lot. The second is the constant buzzing at my thigh. My phone seems to be ringing a lot.

“Action,” I say.

The car begins moving, and from the back seat, I watch the performances. Both Zoë and Jessica have a talent I find mysterious. It’s not simply a matter of them knowing their lines or their voice inflections or their facial expressions. They both make it seem like Chuck, Danny, and I aren’t there, like they’re in a private conversation and speaking spontaneously. This might be an obvious observation of great acting, but whenever I see it, I’m astounded. I say “action,” and they become believable people saying words I wrote months earlier.

The first take is great but I want another for safety. The car backs up and is about to go again when Chance’s voice crackles through the walkie talkie.

“Bradley…Bradley! Have you talked to Marc yet?”

I check my phone and see I have nine missed phone calls from one of our supporting actors. Marc Ewins is playing Mr. Costlow, a perpetually hungover high school science teacher who is Rori’s adult confidant. Marc’s larger sequence has already been shot, but he plays a crucial role in today’s crowd scenes. His wife is also very pregnant.

“What’s up, Marc?” I say when I call him.

I’m standing in the middle of the parking lot away from the rest of the crew.

“I don’t think I can make it today.”

“What?”

“She might be going into labor.”

“That’s not for another three weeks.”

“I know. She might be early.”

“Might be?”

“We’re at the hospital now. I’ll know more in an hour or so.”

“So, you might be able to make it?”

“Ummm…I don’t know.”

“Come on. It’s your second kid, not your first.”

“What does that mean?”

“Nothing. Just let me know what’s going on.”

I hang up right when a jackhammer starts going off on the far side of the parking lot.

“What is that?” I yell toward Chuck and Danny as they sit in the back seat of the car.

We quickly convene, forming a small circle under the parking lot’s slanted sunlight.

“We can’t get clean audio,” Chuck tells me.

“We can’t use the dumpster anymore.”

“What?” I say. “Who’s talking?”

I turn away from Chuck and Danny to see Wyatt and Joe holding bags of garbage.

“The rental agreement says we can’t overfill the dumpster and it’s already full,” Wyatt says.

The rattle of the jackhammer is shaking the asphalt. Two extras have joined the circle.

“Where do we check in?” one of them asks.

“Hold on, one sec,” I say. I back away from the circle: two extras who are about sixteen years old; Chuck with his headphones over his ears, frowning as he twirls his mic toward and away from the construction crew; Joe and Wyatt holding black bags with slow drips of orange juice hitting the ground.

It’s over. We need Marc to make our day. He’s already been in other scenes. I can’t rewrite today’s pages (one of the scenes is the character’s introduction). And we can’t reschedule. Organizing another thirty extras would be impossible, and the production doesn’t have enough money to rent the school for another day.

I stare at my feet as they move away from the jackhammer noise. Suddenly, they’re close to my face: my worn black-and-white sneakers standing flat in the gutter. I’m sitting on the curb.

“I just need a second to think,” I call to the others.

The back of my neck is starting to warm as the sun appears over the top of the school.

“At the very least, we have to finish this scene.”

The voice comes from above me. Zoë has left the car after witnessing what must have looked like a minor meltdown.

“I know,” I say defensively.

“You better not be giving up.”

“I’m not.”

The movie is more personal to Zoë than it is to me. Apart from the many hats she wears, the script’s most harrowing scenes are taken directly from her life. My role as a writer and director is to act as a good steward to her creative vision, to come up with a way to communicate her most vulnerable thoughts and feelings. The movie belongs to the entire crew, but it’s sprung from her passion.

“I was talking to Jessica,” she says. “There are like forty people here. One of them could be Mr. Costlow.”

She’s right. The scenes we’ve shot with Marc as Mr. Costlow have all taken place in the principal’s office. We can find another office somewhere in Boise and reshoot the scenes with a different actor.

“Chance!” I say.

At the inside entrance, he’s telling a group of extras where the bathrooms are.

“Oh…okay…” he says when I tell him he needs to act in the film.

“You have to get off book fast,” I say and hand him a script. “Do you have something that’s more dressy? Like a tie and some slacks and…”

He quickly calls his partner.

Outside again, Wyatt and Joe are loading the garbage bags into the backseat of Wyatt’s car (“It always smells weird in there anyway,” he says) and Chuck is talking to the construction crew at the end of the sidewalk.

“They can’t pause their work,” he tells me. “But!” He twists his hands. “I got them to sign an image release form, so I figured we’d get a shot of the jackhammer and then I can keep the sound in.”

We finish the first scene just in time with the shadow of the building nearly collapsed against the front entrance.

We move inside where the new Mr. Costlow stands at the front of the science class and mumbles words with his eyes closed. Paige is beside him checking the script.

“Nope,” she says. “‘Trashcans ALL around campus…’”

“Oh yeah. ‘Trashcans all around campus,’” he repeats.

“You nearly ready?” I ask. “We’ll shoot over your shoulder first, so you can keep the script in hand.”

Chance is an accomplished actor himself and is clearly excited by the challenge, albeit nervous.

We’re just about to set up for the first shot when my phone buzzes again.

“I can make it,” Marc says.

“What? Your wife okay with that?”

“‘Okay,’ is not quite the word I’d use. But she isn’t having the baby and I can give you two hours.”

“Two hours?”

“Can you make that work?”

I think and look around the classroom.

“Yes.”

In the hallway, I meet with Zoë, Chuck, and Danny. Seated on the carpeted floor, I spread my notecards out and begin pointing.

“Okay, he’s in this shot from scene five, this shot from scene six, this shot from thirty-two—”

“Does he need to be in the lunchroom for Rori’s freakout?” Chuck asks.

“No, you’re right. He’s cut from thirty-two…and he’s in these shots from scene forty-six. So!”

I begin arranging the notecards.

“Things will happen fast, but we’ll have the extras in their Monday wardrobe. We’ll just do Marc’s shot over the class’s shoulder. Then, we’ll run everyone down to the cafeteria for scene six and then run everyone back here with just the front row of students wearing their Friday wardrobe. We’ll wrap Marc and then the front row gets back in their Monday wardrobe for the rest of Rori’s coverage. Then everyone in Friday wardrobe for the other shots of scene forty-six. Then everyone in the cafeteria in Wednesday’s wardrobe for twenty-nine and thirty-two.”

They all stare at me.

“What?” Zoë asks.

“It’s the only way to do it efficiently. We’ll do part of scene five, then all of scene six, part of forty-six, wrap Marc, then the rest of five, the rest of forty-six, then twenty-nine and thirty-two.”

With the plan set in my mind, I’m no longer despondent.

“Will that work?” Zoë asks.

“Yeah, see?” I say, pointing at the notecards. “It’s the only way to make our day and keep Marc in the movie.”

“But can we get all these extras to move that fast? They’ll need to change clothes and run between rooms and we’ll have to set up all these angles and—”

“Zoë, we already did it. We just get to experience it.”

Stockton to Table Rock was released last year. After a successful film festival and theatrical run, it is now available on Amazon Prime.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only