No products in the cart.

Avery—Spotlight City

Over the Pass to a Different Future

By Mary Terra-Berns

Several years ago I worked on Idaho Fish and Game snorkeling surveys of fish above Avery on the upper Saint Joe River, which is federally designated as Wild and Scenic. Twenty-eight snorkeling transects were established in 1969, extending about forty-five river miles from Ruby Creek downstream to Avery. This part of “The Joe” is on the bucket list of anglers across the country.

During the snorkeling surveys, fish species in each transect are counted and their lengths are estimated. I was a rookie at snorkeling and when I floated into a large pool that held hundreds of fish, I popped up and yelled to the biologist on the bank taking tallies, “How do you count this many fish?” He laughed and gave instructions, and I did my best to keep track of all the sleek silvery bodies darting around me.

Right below this large pool was another, smaller pool where a tourist was fishing. He reeled in and waited while we floated through. When we emerged at the other end of the pool, we heard him complain that there weren’t any fish in the pool. With big grins, we told him there were dozens swimming around ignoring his fly.

Avery is forty-seven miles east of St. Maries on the Saint Joe River Scenic Byway. The current population is twenty-five residents, a number that doubles in the summer when Forest Service temporaries and summer residents arrive for a few months.

In Timothy Egan’s 2009 book, The Big Burn, he comments, “Avery is a barely inhabited hamlet along a lonely road, and most of those inhabitants work for the Forest Service. It might as well be called Pinchot again.”

In 1905, the fledgling Forest Service built a ranger station in the upper Saint Joe River valley consisting of two buildings, one the ranger station and the other a post office, which was named Pinchot after the first U.S. Forest Service chief, Gifford Pinchot. The station was located about three miles downriver from current-day Avery.

Fishing the Saint Joe River. Mary Terra-Berns.

Former bunkhouses on the east side of town. Mary Terra-Berns.

The town sign at Ruth Lindow Park. Mary Terra-Berns.

The shadowy Saint Joe. Mary Terra-Berns.

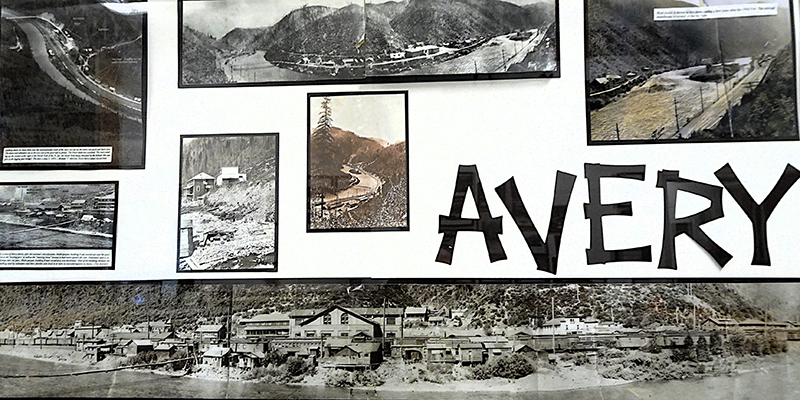

Historical photos in the Avery Museum. Mary Terra-Berns.

The Marble Arch Interpretive Center. Mary Terra-Berns.

The former one-person jail and a railcar. Mary Terra-Berns.

Centennial commemoration of 1910 fire. USFS, CCby2.0

Avery trainyard historical image. Avery Museum.

A Milwaukee Road engine at Avery, 1971. Drew Jacksich, CCby2.0

Milwaukee Road EF-1 class E-45B at Avery, Idaho, in October, 1972. Photographer: Harold K Vollrath. Scanned from a 4x6 print owned by Digital Rail Artist.

Ranger Ralph M. Debitt manned it, while his wife Jessie managed the post office, which was the first this far up the river. The Pinchot Post Office served the few residents but also miners, trappers, and loggers tucked away in the woods surrounding the isolated outpost. Ferrell, a rough-and-tumble town thirty-two miles downstream from the station, was the head of navigation on the Saint Joe and the closest town to Pinchot.

The Debitts weren’t the first to settle in this remote area. Sam “49” Williams (so named for his 1849 California gold rush mining days) built the first cabin at the confluence of the North Fork Saint Joe River and its main section in the early 1890s. In 1894, he filed a homestead claim for land on the north side of the river a quarter-mile wide and extending westward from the North Fork for one mile—essentially where the town of Avery is today. Jake and Lee Setzer settled next to him in 1898 on an adjoining claim, which extended another mile downriver.

In the early 1900s, railroad executives of the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad were keen to have a transcontinental line over the Continental Divide through the Rocky and Cascade mountains to Seattle. In 1906, surveyors located a route through the Bitterroot Mountains at St. Paul Pass for the “Pacific Extension” of what became known as the Milwaukee Road.

Unfortunately, the Pinchot Ranger Station and Post Office were directly in the path of the new transcontinental route and had to be moved. Sam “49” Williams relinquished a portion of his homestead claim to provide a new location for the buildings. After being dismantled and reconstructed, the ranger station was renamed North Fork.

As the settlement grew it became known as North Fork City. Even the railroad adopted the call letters N.F., although the post office was still officially known as Pinchot.

The rail line through Idaho was completed in 1909 to accommodate both freight and passenger trains. Laborers came from numerous countries but many were Japanese. The Milwaukee executives agreed to hire Japanese labor in exchange for getting their foot in the door of the lucrative Japanese silk trade. About eighty Japanese workers lived in a neighborhood on the west side of North Fork City, and every year they invited the rest of the town to celebrate the Japanese emperor’s birthday with them.

William Rockefeller served as a director of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway Company for forty years. His son, Percy Avery Rockefeller, had a son in 1903 who was named Avery. Locations along railroad lines were typically named after the executive’s family members, and on February 14, 1910, the stop was renamed Avery, although for a time the government retained Pinchot as the post office’s moniker. Approximately two hundred people lived there by then.

In 1910, heavy snowfall accumulated during the winter but it didn’t linger. April was hot and spring rains were scarce. Exceptionally dry conditions continued throughout the summer. By late August, District One Forester William Greeley reported that approximately three thousand fires were burning in northern Idaho and western Montana. Many were started by cinders that escaped the smokestacks of coal-fired locomotives traveling on the Milwaukee Road through the bone-dry forest.

On August 19, an electrical storm blew through the Inland Northwest and spewed lightning bolts into the forest, which ignited dozens of additional blazes. The next day, hurricane-force winds raced across the Palouse hills to create an uncontrollable firestorm, which became known as the Big Blowup or Big Burn [see “Racing the Flames,” IDAHO magazine, April 2019]. Even as the big wind hit, railroad employees were frantically trying to put out fires along the tracks and trestles.

One Milwaukee train was traveling through smoke and flames on its way to Avery from Montana when a man on the tracks flagged down the engineer, John Mackedon, and told him the town of Grand Forks, northeast of Avery, was engulfed in a blaze. The conflagration was heading towards Falcon, about two miles from Grand Forks, where terrified evacuees waited on the tracks to be rescued.

Mackedon backed the train to collect the newly homeless and transport them to Avery. Another train similarly crowded with refugees from the woods and lost towns also attempted to make it to Avery but the fire was too intense and the engineer, C.H. Marshall, stopped the train in the safety of one of several tunnels on the Milwaukee Road.

Avery was surrounded by flames and desperate measures were taken to evacuate residents by train. Soldiers from the 25th Infantry—the famed Buffalo Soldiers—were sent to Avery on August 17 to assist with maintaining order and for fire control. When orders came from Ranger Debitt and Shoshone County Sheriff H.D. McMullan to evacuate the town, the soldiers helped women and children aboard passenger cars.

In about a half-hour the train pulled out of Avery heading west to Tekoa, Washington. Some of the soldiers stood on the railcar platforms to reassure passengers that they would reach Tekoa.

The August 28 Seattle Daily Times carried a story from a contributor called “the first man to reach the outside world from Avery, Idaho.” Thaddeus A. Roe, a forest ranger, described efforts to fight the fire and the loss of twenty-four of his firefighters at Setzer Creek. When he and the remaining fifty-eight firefighters realized their efforts to fight the blaze were hopeless, they made their way to Avery as the fire ate away at their escape route.

When Roe and his men reached Avery, they joined with the few remaining residents and Buffalo Soldiers to start a backfire, which quickly moved uphill and increased in intensity as it went. Within minutes, the backfire met the wildfire as it made its way down the slope towards town. The roar of the colliding flames was deafening, yet the crash caused both flame-fronts to collapse and fizzle out.

The next day Roe and a group of his men made their way back up Setzer Creek to search for their missing colleagues. Their quest ended in anguish. In the Seattle Daily Times article, Roe described the search for the twenty-four (other references say twenty-seven) Setzer Creek firefighters, all of whom burned to death. They were wrapped in canvas bags and buried where they were found.

The Buffalo Soldiers, the surviving firefighters, and the few remaining local Avery men who lit the backfire and doused spot fires around town throughout the night were praised as angels and heroes. Communication wires were repaired quickly and messages were transmitted that Avery had survived relatively unscathed.

In 1912, the Forest Service secured a plot for the fallen firefighters in the St. Maries Cemetery. A commemorative monument was placed and by 1925, the bodies of firefighters from Setzer Creek and Big Creek, near Wallace, had been exhumed and reburied there.

The numerous newspaper articles, stories, and references concerning the events of the 1910 fire often differ in details. This is understandable, considering the panic and chaos, as well as the dispersal across the region of people who lived and worked in the forest.

Three million acres of forest in northern Idaho, western Montana, and eastern Washington were reduced to ash and burnt tree trunks. Although Avery was saved, several other towns were turned to rubble and dust, never to be rebuilt. A few towns, such as Wallace, Kellogg, and Osburn, were burned or partially burned and rebuilt.

At least twelve bridges along the Milwaukee Road burned, including one that was 725-feet long. But the rebuilding effort, flush with Rockefeller money, didn’t take long. The depot in Avery was still intact and personnel returned to their cabins on the west side of town and manned the station with little delay. A small upside to the absence of trees in the hills was that residents had a few more hours of sunshine to get back to daily life.

The Milwaukee Road had a long, storied history in Avery yet it struggled financially to keep the Pacific Extension afloat. The line filed for bankruptcy a third and final time in 1977. Even as the company awaited the ruling from the Interstate Commerce Commission for abandonment of the rails west of Miles City, Montana, the last train passed through Avery on March 17, 1980.

Last October, I took a drive on the “lonely” road Egan described in The Big Burn. I left Coeur d’Alene before the sun was up. The air was cold but a clear sky indicated a beautiful fall day was in the making. Highway 3 to St. Maries was quiet except for a few logging trucks on their way to the mill.

At St. Maries I turned east onto the Saint Joe River Scenic Byway for the forty-seven-mile drive to Avery. The road was quiet—I wouldn’t say lonely, just quiet—which was fine by me because I could lollygag and take pictures.

The fall colors were fabulous. At the twelve-mile marker is a large meadow where the raucous town of Ferrell once stood. Across the river, Saint Joe City sprang up when Mr. Ferrell insisted on one hundred thousand dollars to allow the train to come through his town. Railroad executives balked, laid the tracks across the river, and were followed by many of the businesses in Ferrell. Today Saint Joe City is a small unincorporated community on the south side of the river.

As the sun inched higher into the sky during my drive, the mist on the shadowy Saint Joe started to lift and the temperature ticked up a few notches. I passed several campgrounds along the way, the small town of Calder, and Herrick on Big Creek. Fifteen miles downriver from Avery, I stopped at the Marble Creek Interpretive Center. For anyone interested in the logging history of the area, this is a great stop.

As I passed Setzer Creek and slowly came into town, I was definitely not on a lonely road. People were all along the river and at campgrounds and RV sites, although it was less busy now than in the summer.

Compared to the hour it took me to cover those forty-seven miles, consider that a hundred years ago I would have had to board a steamer in Coeur d’Alene for the trip to Saint Joe City and from there, gone by horse or foot. I don’t think I could have poled a canoe up the Saint Joe River against the current for thirty-five miles to reach Avery.

I arrived at the west end of Avery, turned off the highway, and stopped at Ruth Lindow Park in the middle of town. It’s next to Avery Depot, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Tucked inside the depot I found the post office as well as the library, community center, and museum, which contained all kinds of interesting photos and artifacts from Avery’s history.

Adjacent to the depot and part of the museum is a restored Milwaukee Road passenger car open to the public. Just outside the depot and in front of the railcar is a trout pond built around 1912 to provide entertainment for passengers while they waited for their train. Next to the trout pond is the old one-person Avery Jail.

Before I walked to the historic Pinchot/North Fork Ranger Station, I went over to the local coffee

hut. While the owner got my coffee and heated my cinnamon roll, she told me she was working on a batch of chili for the town’s Fall Cider and Chili Party, which would take place in a couple of hours. Proceeds would go toward repairs to the railcar.

I ate my cinnamon roll and took the rest of my coffee on the five-minute stroll to the ranger station, also on the National Register of Historic Places and next to the current bunkhouse for Forest Service employees. During the warmer months the bunkhouse is a busy place but on this day the building was quiet. The ranger station is a private residence now.

As I walked back down the hill to my vehicle, I noticed a crowd of people at the coffee hut and more vehicles filtering into town. Side-by-sides and four-wheelers arrived in small groups. Almost everybody was coming from Wallace via the Moon Pass Road (Forest Service Road #456).

At the local pub, staff warmed up the cider and got ready for the chili cook-off competition. Another group of ATVs rolled into town, their drivers looking forward to tasting and voting for their favorite recipe.

I enjoyed the beautiful day by making my way over Moon Pass to Wallace and then back to Coeur d’Alene. Moon Pass Road, initially called the Bullion Road (to the Bullion Mine), was the first wagon road into the area, predating the Milwaukee Road by a few years. Seven of the original train tunnels are spaced out along the road until you reach the old Pearson Siding, where mining equipment was brought in by rail for the Lucky Swede Mine.

This spot is now the lower access site for the Route of the Hiawatha, a fifteen-mile biking and hiking trail that follows the old railway. At each tunnel, I had to wait for large ATV and 4WD groups from Wallace to come through on their way to the chili cook-off. As I waited for my turn to go, I enjoyed the scenery and kicked myself for not bringing my fly rod.

In the past few years, Wallace to Avery over Moon Pass has become a popular day trip. On any given day a variety of vehicles come over, bound for Avery. Each November, Avery hosts a community Thanksgiving dinner and I was sure there would be more than a few vehicles traveling the pass for a turkey dinner. In the winter, Avery is just as busy with snowmobilers.

Even though Egan’s “barely inhabited” comment about Avery, with its twenty-five residents, is accurate, that doesn’t mean the town is fading away. A 2013 story on Boise State Public Radio News noted that contrary to popular belief, Avery and many other small towns are holding their ground, not dying out.

Reporter Jessica Robinson said, “More often, they’re changing—demographically, economically. And the signs are there in Avery, too, that the future isn’t dim—just different from the past.”

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only