No products in the cart.

Back Then in the Valley

By John W. Lundin

Photos courtesy Center for Regional History, the Community Library, unless otherwise noted

I first skied in the Wood River Valley in 1960, after a twenty-four-hour train ride from Seattle, when a week-long ski pass at Sun Valley cost thirty-nine dollars. We left Seattle on a southbound Union Pacific train at 10 p.m., and after more stops than I care to remember, we arrived in Portland at 2 a.m. We waited for two hours on hard benches at the Portland depot, and then headed east on the Portland Rose. The sun rose and set as we rolled through Oregon and Idaho in our coach seats, and the train reached Shoshone at 10 p.m. the next night. Buses took us the rest of the way to the resort. People who believe traveling by train was exciting or romantic never made that trip.

This was the start of my long association with the area, where I have had a home since the early 1980s, but the Wood River Valley was a significant part of my life even before then. Riding the train to Idaho in 1960 was a return to my roots, since members of my family were early settlers in the valley. In 1881, my great-grandparents, Matthew and Isabelle Campbell McFall, and Isabelle’s brother Neil Campbell, were drawn to Bellevue by the silver strike. The McFalls built the International Hotel in Bellevue, the valley’s high-end facility. Neil had Bellevue’s first blacksmith shop, operated a stagecoach line from Bellevue to the mining settlement of Muldoon, and he and his sons owned several large farms and forty-one silver mines over the years. In the 1920s and early 1930s, Neil’s son George Campbell was Blaine County Sheriff, and another son, Stewart, was Idaho Inspector of Mines, an important elected post.

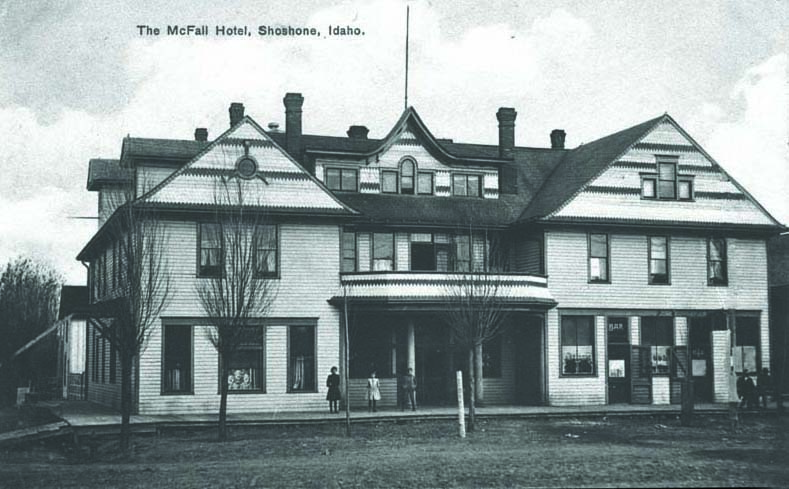

The McFalls moved to Shoshone in 1893, when an international collapse of silver prices shut down the mining industry in the Wood River Valley. At the time, Shoshone was thriving as a railroad center. My family built the McFall Hotel, which became the center of Shoshone’s social and political life. In 1960, when my train arrived in Shoshone, I waited for the Sun Valley bus at the McFall Hotel.

McFall family, 1888, Bellevue. Courtesy John W. Landin.

Otto Lang helps the Shah of Iran with his skis.

McFall International Hotel, Bellevue, 1880s. Courtesy John W. Landin.

McFall Hotel, Shoshone, early 1900s. Courtesy John W. Landin.

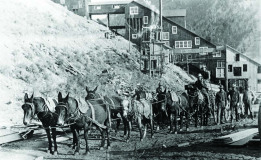

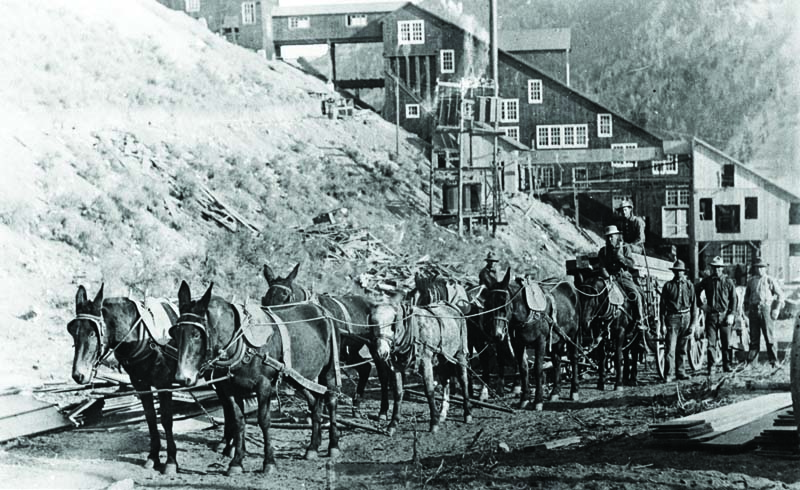

Fast freight wagon at North Star Mine, Ketchum, 1885.

Oregon Short Line, Wood River Valley, 1880s.

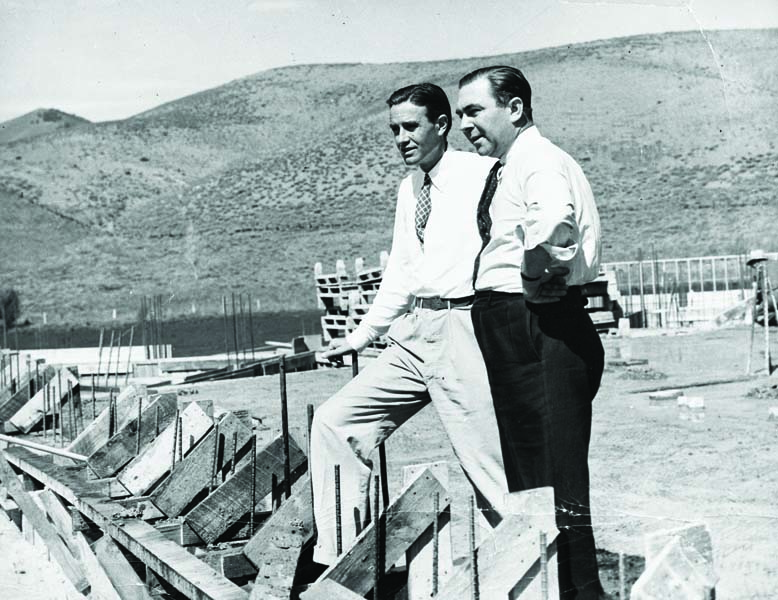

Averell Harriman and Steve Hannigan inspect the lodge being built.

I’m retired from a career as a trial lawyer in Seattle, and have been researching and writing for the past decade about the history of the Wood River Valley, focusing on the experiences of my relatives. Forty-three of my essays are available at the Center for Regional History of The Community Library in Ketchum. I’ve also written two books about the history of the area. An important part of my research has concerned the impact of the Union Pacific Railroad on Idaho and the Wood River Valley.

Between 1881 and 1884, Union Pacific built a Northwest connection from its cross-country line that extended from Granger, Wyoming, to Portland, Oregon. The Northwest connection, built using the subsidiary Oregon Short Line, followed the route of the Oregon Trail through Idaho. This gave the railroad access to the riches of the Willamette Valley, Puget Sound, and the growing trade with the Orient, even as it connected Idaho to markets all over the country. The Wood River Branch was built between 1882 and 1883, from Shoshone to Hailey (and extended to Ketchum in 1884), to serve the mining industry.

The branch line connected the valley to the outside world and brought in large amounts of capital that was invested in the mining industry, resulting in an economic boom. When the silver depression shut down mining in the 1890s and forced Union Pacific into bankruptcy, agriculture and sheep-raising became the area’s main industries. After the Reclamation Act of 1902 provided federal funds to build dams and irrigation systems in the arid west, central Idaho deserts became productive farmland, and new communities were formed. The railroad thrived and expanded to serve these new agricultural markets. This economic base, supplemented by the partial restoration of the valley’s mining industry, kept the Wood River Branch in service despite the onset of the Great Depression in 1929.

Each of the valley’s economic eras depended on its rail connection to the outside world. Sun Valley Resort was built in the remote mountains of central Idaho in 1936, not only because the area had the perfect combination of snow, weather, and hills, but, crucially, because it was served by an existing Union Pacific line. Without that line in 1936, the resort would not have been established there.

One of the most important sources of materials for my writing about the Wood River Valley’s history is the Center for Regional History. It holds numerous Union Pacific materials, including two thousand pictures that make up a part of its collection of around fifteen thousand historic photographs. The center has more than five hundred oral histories that provide unique personal views of the valley’s history. These include Sun Valley founder Averell Harriman and his daughter Kathleen, Union Pacific engineers and officials, ski instructors, famous skiers, movie stars, and numerous others, from which I’ve drawn many fascinating anecdotes and stories. Accordingly, I’m donating my profits from my two books on the area to the center.

I also was fortunate to obtain the assistance of railroad historian Maury Klein, professor emeritus of history at the University of Rhode Island. Professor Klein gave me access to Union Pacific documents he obtained when writing his multi-volume history of the railroad, said by Oxford University Press to be the definitive work on one of America’s iconic companies. The documents provide valuable insights into Union Pacific’s construction and management of Sun Valley, and the key role of Averell Harriman, U.P.’s chairman of the board. According to Averell’s biographer, Rudy Abramson:

For five years, Harriman fussed over Sun Valley as he had none of his other business enterprises. Whenever there was repainting, samples had to be kept to prove to him that the original colors were unchanged. He dictated the precise location of the furniture in the lodge’s famous Duchin Room, ordering it moved if he arrived and found chairs and tables had drifted from their original places.

Railroad economics determined the resort’s status and future. The subsidy from Union Pacific to keep Sun Valley in operation (ultimately approaching one million dollars per year), caused tensions within its board, nearly led to a decision not to reopen the resort after WWII, and resulted in its sale to the Janss Company in 1964. Harriman said Sun Valley operated with a deficit, but “we didn’t run it to make money; we ran it to be a perfect place . . . and the publicity I thought was worth very much more than the deficit.”

As a person who has skied for much of my life, learning on wooden skis and leather boots. So I was fascinated to discover that Harriman’s use of ski racing was an important part of his plan to make the resort an international ski destination. The Harriman Cup was the country’s most prestigious and competitive event, attracting the best skiers in the world. When Sun Valley opened in December 1936, it was the country’s first destination ski resort. It became known as the “St. Moritz of America,” an image magnified by articles in Life magazine, railroad trade magazines, and newspapers and magazines around the country. Then-famous ski racer Dick Durrance said Sun Valley was “the most important influence in the development of American skiing . . . Its concentrated and highly successful glamorization of the sport got people to want to ski in the first place.”

Designed to replicate the romance of European ski areas, the resort had a monopoly on skiing grandeur for several decades, and was the model for ski areas that developed later. When Averell Harriman left for government service in 1940, ending his formal role in Union Pacific management, he left the fate of the resort to railroad men who never fully supported it. Sun Valley almost failed to reopen after WWII, because of U.P.’s concern over the subsidy necessary to keep it operating. When it did reopen in the winter of 1947, U.P. managed it with a different philosophy. No longer was its primary market the rich and famous, but it attracted families, ordinary skiers, and convention traffic.

Even so, the Harriman Cup races continued to attract the best skiers in the world, while the resort played a key role in the training and selection of the 1948 and 1952 U.S. Olympic ski teams. Its ski school employed Olympians such as Christian Pravda, Stein Eriksen, Emile Allais, Franz Klammer, Jack Reddish, and Barney McLean. According to railroad historian Maury Klein, as passenger traffic continued to decline in the 1950s, the resort’s economic losses became less acceptable. This led to the decision in 1964 to sell it. The Janss Company made it a year-around community, but lacked the money to take it to the next level. In 1977, the company sold the resort to the Holding family, owners of Sinclair Oil Company, who invested substantial money into it and restored it to international status. But nowadays, unlike the 1930s and 1940s, Sun Valley competes with numerous other resorts that started after WWII.

I hope to write three more books about Idaho. One would be a history of the Oregon Short Line Railroad and its impact on Idaho’s economic development. Another is the story of Robert and Carrie Adell Strahorn, Union Pacific publicists and authors who convinced the railroad to build the Wood River Branch in the 1880s, and developed a number of new railroad towns. The third would be a history of the Wood River Valley, centered on the lives and experiences of my relatives.

The author’s book, Sun Valley, Ketchum and the Wood River Valley, published in June, is part of the Images of America series from Arcadia Publishing. It showcases two hundred historic photos. A second book, Skiing Sun Valley: a History from Union Pacific to the Holdings, contains 160 historic photos, and will be out November 9 from History Press.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only