No products in the cart.

Lentils and Rice

A Week in the Woods with At-Risk Youth

Story and Photos by Francisco Lozano

I had lost count of how many days we had eaten lentils and rice. The fire building duty that morning was assigned to a boy I’ll call John, a resident of Project Patch who struggled with self-confidence.

The assistant director of the boys’ dorm, Wes Smith, explained to me that when a young man built a fire, it also helped to build his sense of self. I had recently joined the direct care staff of this non-profit ranch for at-risk youth in Garden Valley and had plenty to learn in my own right—but it was taking John a long while to get the fire started.

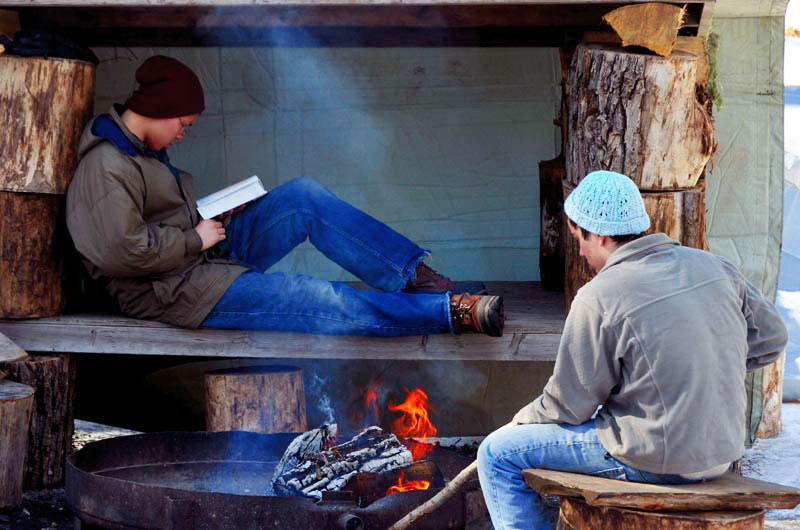

Tending the fire is a key task during wilderness camp.

A resident of a Garden Valley wilderness program for at-risk youth keeps an eye on the fire.

The goal of the program is to get back to the basics of a quiet life with few distractions. This time helps them regain hope and focus.

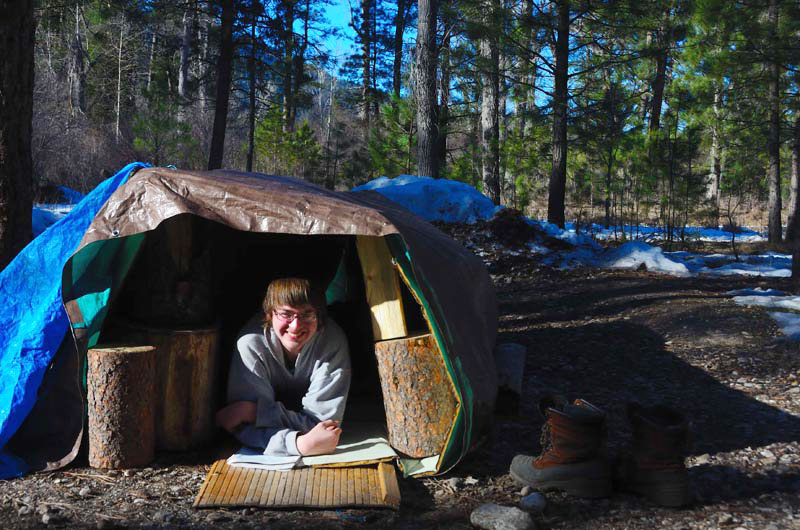

Conditions are not luxurious, but the youths often thrive.

Putting up a shelter.

A rudimentary but nourishing breakfast.

With the help of adults, the teenagers make shelters of beams and tarps.

Inspirational reading by firelight.

A symbol of hope over the ranch.

Each day, the designated fire-builder was given paper and three matches, but John was running through his supplies and was about to give up. Meanwhile, other boys with more experience were eager to take over. This wasn’t allowed. Instead, John was coached and given tips until he finally got the fire going. When it was at full blast, he looked into it pensively, almost as if he could see himself reflected in it, like an image in water. I quickly reached for my camera to capture the moment.

I approached and interrupted his reflections to ask, “Do you want to see a picture of what success is like?”

“You’re just going to show me a picture of the fire,” he replied.

When he saw himself in the photo, a smile broke out and his eyes sparkled. I didn’t capture that moment on camera, but I’m sure it will last in both our minds.

Three years ago, I didn’t know Project Patch existed, and just two years ago, my wife Donna and I knew nothing about Idaho. We certainly didn’t know we would be moving from Los Angeles to the mountains of Garden Valley. During the recession, our restaurant failed, and we became weary of the big city life. We longed to move to a mountain area, and Donna, a family therapist, began looking for opportunities. I had worked in the hotel and restaurant business all my life, and wasn’t sure what I would do for a living in the mountains. I had gone to photography school but had never worked at it professionally. And then Donna was hired as a therapist at Patch. After a stint as a Garden Valley restaurant manager, I volunteered for three days at the ranch, fell in love with what they were doing, and joined the staff.

The ranch, licensed by the state for residential treatment for at-risk teens, also includes an accredited high school on the property. Young people stay at the ranch for an average of one year. Parents place their teenagers there when it isn’t safe at home for them and no therapeutic plan in the local community addresses the problem. Many of the youth are negative about relationships, skip or do poorly in school, encounter or react with anger at home, and experiment with alcohol and drugs. The ranch also works with young people who isolate themselves from friends and family, or spend the majority of their time in fantasy and online gaming.

During their time at the ranch, the residents attend group counseling, school, individual counseling, work projects, recreation, and religious services. To me, it looked at first like a typical school or summer camp, but I soon realized that everything was focused on getting the teens emotionally healthy enough to return home without hurting themselves or other family members.

Once a year, a client participates in a therapeutic wilderness program, which I call “Lentils and Rice,” because that’s what everybody eats for many of the meals. The goal of the program, which takes place on the campus within walking distance of the dorms, is to get back to the basics of a quiet life with few distractions. The young people focus on what they want to do with their lives, their personal journeys, and often they realize that the path they are on makes them feel hopeless about their future. This time in the outdoors frequently helps them to regain hope and focus.

Last March, I went to the wilderness site with two other staff members and four boys, including John. With the help of the adults, the teenagers made shelters of beams and tarps. We staffers slept in a rustic cabin, but we spend most of our time outside with the kids.

During the week the residents spent in the woods, they were not allowed to talk to each other and had to sign their needs to staff, speaking only if given permission. They cooked their own meals every day on the open fire in tin cans, and worked on written assignments we gave them. Aside from that work, the only reading they did was of inspirational writings.

My first day at the camp, the assistant director, Wes, asked me to read something. I hadn’t planned on this, but I pulled out my smart phone and read from one of the books in my library, which I could still access even though I had no phone reception. I chose an inspirational book and read a chapter called “In the Wilderness.”

The next morning, Wes assigned work duties to the boys, which had to do with keeping the camp functioning properly. The sole of Wes’s boot was coming apart, so he wrapped it with duct tape, which was my first lesson in the value of that material to the wilderness program. Later, I watched boys create flip-flops with insoles by wrapping duct tape on them. When my dog chewed on the strap of my expensive, arch-enhanced sandal, I duct-taped it.

Every day, the lunch menu was lentils and rice, fruit, and whole wheat bread. One boy who was an Eagle Scout decided to start a water conservation program to wash the tin cans after each meal. He filled them with snow, which he boiled over the fire. After lunch, Wes said an outdoor shower had to be installed, and the boys were given plastic buckets to haul water from the river. They heated half the water on a boiling pot and combined it with the cold water, making it warm compared to the outdoor temperature in the mid-30 degrees.

During a group counseling session, the topic was forgiveness, and one boy told how his mother forgave her husband every beating he delivered, going back to him time after time. This inspired me to talk about how my older sister was in an abusive relationship with the father of her three children. Sharing the story of how I had witnessed a beating when I was sixteen, I tried not to choke on my words as I admitted how guilty I had felt all these years, because I had done nothing about it. Before I could finish the story, I was sobbing. I found out there is healing in helping to heal others.

All the boys gave me a hug but one, a youth whose step-father physically abused his mother. This boy typically kept his emotions to himself, but I could tell he was touched by the story.

The following week, when Donna and I came back to the wilderness program for our shift, only one boy was left from the original group. He was still struggling against staff directives, did not do his counseling, talked without permission, and whenever he was put in charge of building the fire, he played with it too much. The staff decided he needed to stay longer in the wilderness program.

Every morning at the outdoors site, the boys would be brought into the cabin to warm up their toes and fingers. The first one to rise in the morning would be in charge of building the fire, and right after warming up, he would go back out to cook our oatmeal breakfast. After cooking three meals a day in the open fire, we all smelled like smoke.

In the evenings we would see deer, grouse, and perhaps an eagle or two during our walks. Once, while a resident was working on his assignment, four turkey vultures hovered above him. One of the birds did its business in mid-air, dropping a deposit on the boy’s assignment. A rule during wilderness is not to laugh at anyone, but the title of the boy’s assignment was “Focus on Emotional Abuse.” Everybody had to laugh, including staff.

Such moments of bonding are what Project Patch founder Tom Sanford sought to create during the many years he and his wife ran the ranch. In the dorm, Wes often would read to the boys from Sanford’s book, Wounded Healer. It has been inspiring for me to learn how time and again over the years, when the ranch was struggling and Tom was at the point of becoming dispirited, some donor or other would make it happen again, and the ranch’s leader would be refreshed and renewed.

Today, as I finish writing this story four months after the wilderness program, looking at my notes and sorting through photos, I find that I’m getting hungry and I’m craving, yes, lentils and rice.