No products in the cart.

The Idaho Cut

Art Becomes a State Symbol

By Stephen Q. Howell

Photos Courtesy of the Howell Family

When I was young, our family sometimes drove to Dismal Swamp, which is about ten miles northwest of Rocky Bar, up Trinity Mountain Road deep in the Boise National Forest. It was family tradition to go camping with my parents in the more remote reaches of Idaho to gather gems. At Dismal Swamp, we sifted water and rocks through big screened trays in search of smoky quartz. It was a lot of work and I found only a few rocks that I wanted, which mostly were smaller than what I was looking for. I also remember going to Emerald Creek in the Idaho Panhandle National Forests to look for star garnets but I’m a reader and on most of these excursions when I was growing up, I had my nose buried in a book and didn’t pay much attention to the route. My father knew where he was going and he drove quite slowly, so there was no reason for me to keep track. We spent the nights in Dad’s camper and the days gathering agates, jaspers, smoky quartz, and other precious specimens of Idaho’s bounty. These experiences were part of what led me to become a gemologist and a faceter, like my dad.

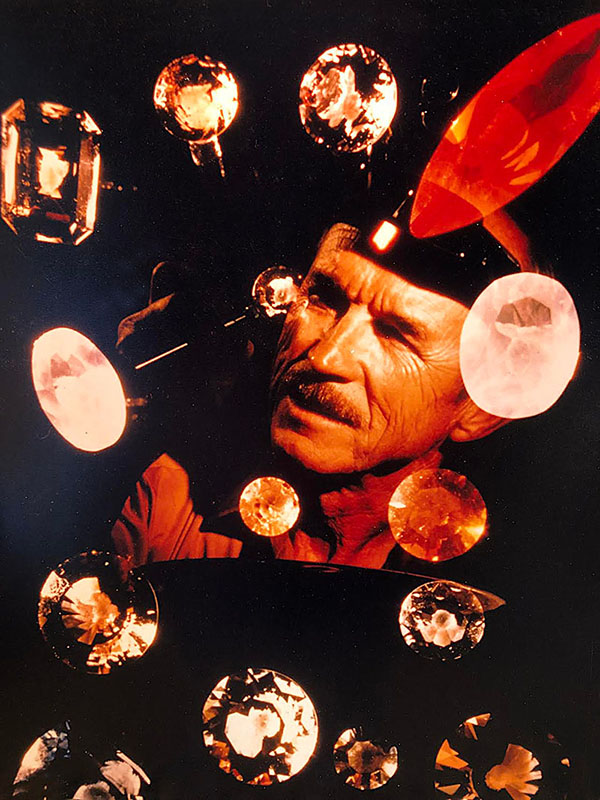

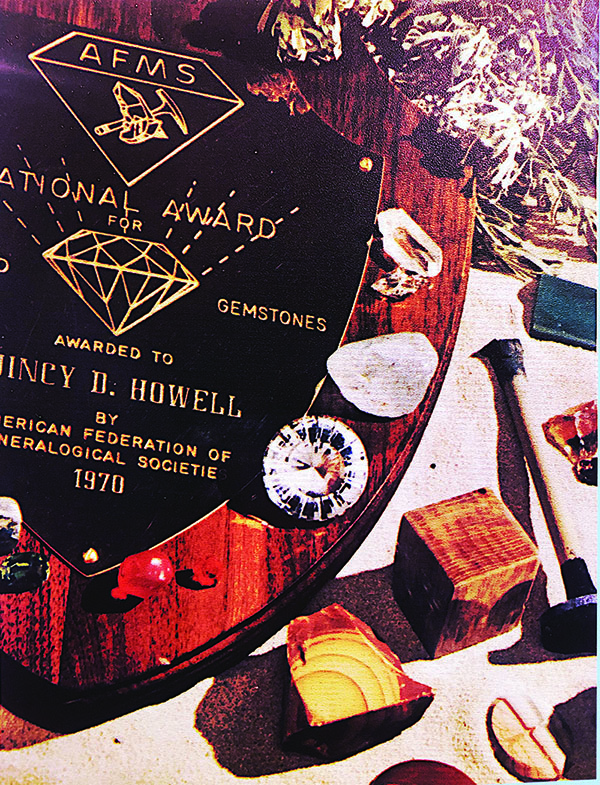

Quincy Douglas Howell was world-renowned at faceting gemstones, which is the artful placing of flat polished surfaces onto a stone to bring out its inner beauty by bouncing light around inside the stone before it escapes. He practiced this art for thirty-five years and was considered one of the world’s top experts. In 1970, he won the US championship in faceted gemstones from the National Federation of Mineralogical Societies. In 1974, he was featured in a National Geographic article, “The Glittering World of Rockhounds.” In 1979, the Idaho Statesman published an article about him titled, “Portrait of a Distinguished Citizen.” He was awarded a lifetime membership in the Idaho Gem Club, was inducted into the National Rockhound Hall of Fame, and some of his best stones are owned by the Smithsonian Institution.

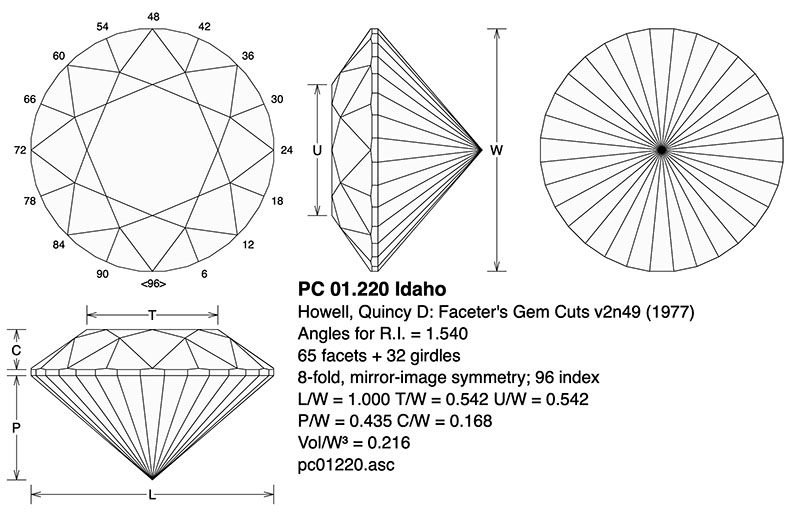

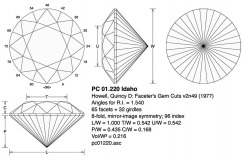

The final assembly of facets is referred to as a “cut” and in 1977, Quincy (or “Q” to his friends) finished a unique and new cut of great beauty. He felt that it was the best design he had ever developed. It reflected light in a way that was not only gorgeous but almost mesmerizing. It was the best of the best, a faceting pattern that I and others think is brighter and more beautiful than the Brilliant Cut used for most diamonds. He decided to name it after the state he loved most: the Idaho Cut.

My dad was born in 1908, the fifth of eleven children. His family had very little money and he worked his way through college by serving food in a sorority house. He made extra money by enrolling in Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) classes, where young men trained to become officers and were paid a little for their efforts. He graduated from the University of Oregon during the Great Depression and found it difficult to find work. When he joined the Army prior to Pearl Harbor, he became a second lieutenant and had a regular paycheck, but he fretted about how he would be able to earn extra income once he was living on his Army retirement pay. He cycled through several artistic hobbies, including photography and wood-carving, as I recall. In 1955, when he was stationed in Mountain Home, he discovered that rockhounds made jewelry from stones you could pick up off the ground, for free. He became an Idaho rockhound and embraced the Gem State in all aspects.

Quincy Howell cut and catalogued more than 6,500 gemstones.

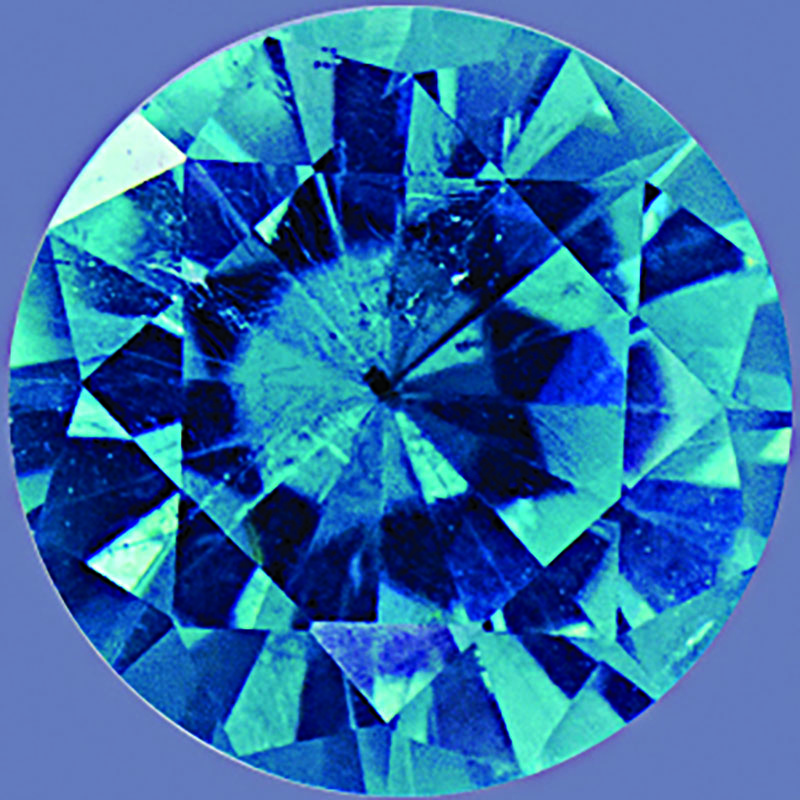

An Idaho Cut of cubic zirconia.

The diagram of the Idaho Cut.

An Idaho Cut of periodot.

An Idaho Cut seen from the bottom of a gemstone.

In the family camper, the author is in the middle right and Quincy is beside him.

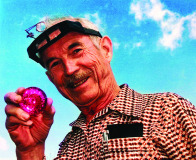

Quincy with the largest stone he cut, a synthetic material called a laser ruby.

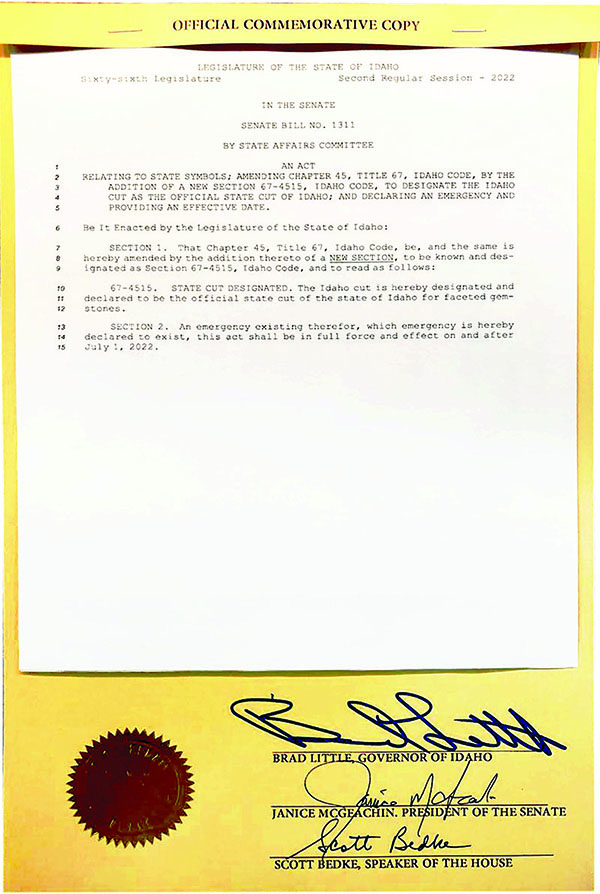

Commemorative copy of the Idaho Senate's bill.

A collage of Quincy and his stones given to him by National Geographic.

His national award, presented in 1970.

Pink tourmaline.

Quincy with his wife, Edna "Tej" Howell.

A collection of his gemstones.

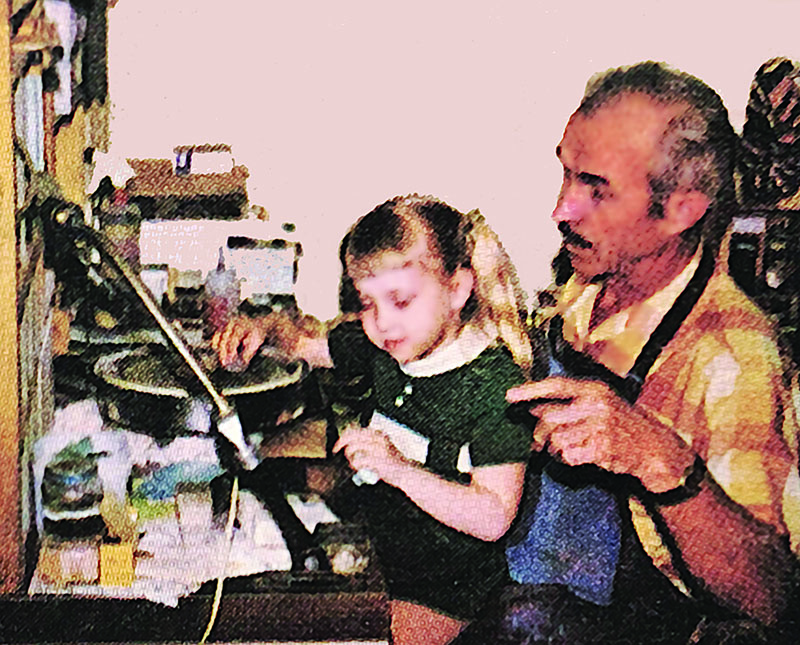

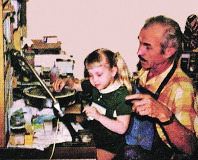

Quincy with granddaughter Wendy.

When the military sent him to Thule, Greenland, for a year, my father agonized about how he could do lapidary work there without any Idaho agates, petrified wood, or any of the required heavy machinery. Luckily for him and us, lapidary includes the option of faceting. So he bought a faceting machine, an instruction book, a cigar box full of raw gems (referred to as “rough”), and took all this with him to Thule, where he taught himself to facet.

When he came back from Greenland with his new hobby, I could not wait to try it. I bought a faceting machine and used it during our summer vacation trips. But I was mostly interested in becoming a gemologist, which meant being able to identify the many varieties of natural and artificial stones, for which our family’s field trips were very helpful. In many places we dug for agates and jaspers, all beautiful, although we were looking for the larger chunks that could be cut on a diamond saw into slabs and made into cabochons, which are stones cut into a convex form and highly polished but not faceted. There was amethyst near Hailey, citrine around Weiser, and I was so excited about Owyhee jasper and plume agate near White Bird Hill—all perhaps entirely dug up now, so much rock that is precious today. We thought there was a forever supply, but mankind seems to be greedy about such things.

All our many trips were taken in Dad’s little camper. My brother, two sisters, our parents, and I ate in shifts at the tiny table. Dad wore out that camper’s engine. He reasoned that oil does not wear out, so he thought changing an engine’s oil was not needed. He figured it was a ploy by the oil companies to sell more oil and it didn’t occur to him that changing the oil would remove dirt and byproducts from the engine. When the engine began squeaking so badly that I asked him what was wrong, he couldn’t hear it, because military exercises had damaged his hearing. Eventually, no oil was circulating and the top of the engine under the valve covers was dry, but it still ran, kind of. He didn’t trade it in until it simply couldn’t be fixed anymore.

One time, he and a couple of friends mounted an enormous saw on a trailer so they could go into the backcountry and cut up slabs of petrified logs and agates to haul them out. That project didn’t pan out too well. A diamond blade must run fast and true, and by the time that they manufactured the saw and the trailer, the darn thing was much too heavy to haul into the muddy fields where the rocks would be found.

My father was active in the Boise Area Rockhounds and the Idaho Gem Club, but he also developed associates and friends around the world. Sometimes we went with him to gem and mineral shows at fairgrounds where his faceted stones were entered in judged competitions. Winning blue ribbons was common for him. He was not only talented but a perfectionist, and had the time in his retirement to do things right. He eventually became a faceting competition judge, which further widened the circle of his friends and associates. My mother Edna “Tej” (pronounced “Tedge”) Howell, who was born in Albion in 1918, became remarkable in her own right at making and mounting gems in settings for rings, necklaces, and earrings. The couple was deeply in love their whole lives.

When Dad designed the Idaho Cut, computers that could trace paths of light through stones had not yet been invented, so this assessment had to be made just by looking at it. Each person’s viewpoint can be different, and each kind of stone requires different angles, and the “brightness” and “flash” of a stone are affected by how light or dark its color is—all of which makes the beauty and brightness of faceted stones more subjective that it may seem.

After judging for many years, Dad understood this and attempted to determine what affected people’s opinion about each faceted cut. He would facet two stones with different cuts and ask people which was best and brightest. Over time, he was able to get a better grasp of what people saw and liked than the jewelers who designed the Standard Brilliant Cut that is used for the majority of the diamonds sold today. That cut is good for diamonds, but the Idaho Cut is arguably better for other stones. Of course, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. You need just ask any bride what the most beautiful stone is that she has ever seen.

Q was a relentless experimenter who challenged everything he read or was told by experts. Many of these discussions and experiments were about how to make a stone more brilliant. He once faceted one hundred stones, all from a single piece of quartz, and all of them with exactly the same angles and facets, oriented along the same axis. He polished each of the stones separately with a different polishing compound or combination of compounds, or on a different polishing surface. He used every substance imaginable to polish them, including toothpaste and scouring powder from the kitchen. He then asked others which stones looked best to them.

It was a staggering amount of work, but there was no other way to determine what looked best to the human eye. I still have those stones in my collection, although the actual stones were not labeled individually and the box that he kept them in was not secure, so they are all jumbled with no way on Earth to set them right. It was a project that probably will never be repeated, but his dogged approach slowly zeroed in on what looked best to most people—except, of course, for the blushing bride.

He once faceted a set of stones that could be disassembled into a top and a bottom and then be reassembled with a selection of other tops or bottoms, or rotated to see the play of light and color that resulted. As he came to be considered a Picasso of faceting, Q began to name and register the cuts he invented. The consummate husband, father, and grandfather, he invented cuts for family members, mostly the women, who wore the stones named after them. He was a prolific faceter and could start and complete a stone in less than an hour. He completed more than 6,500 stones and meticulously cataloged each one. He also taught more than one hundred people how to facet.

Our family has always been very close-knit, even after my siblings and I grew up and moved away. Q passed away in 1992—three decades ago—yet his presence is still deeply felt by every family member who is old enough to have known him. Six family members have “Quincy” as our first or middle name in his honor, and it is a common occurrence at family reunions to talk about him and my mother, which unlocks many wonderful memories. Although both are long gone, their memory still brings us together.

About three years ago, we began to discuss how to get the Idaho Cut recognized as a symbol for the State of Idaho along with other symbols such as the mountain bluebird, cutthroat trout, Appaloosa horse, syringa flower, Idaho star garnet, and so on. Considering that Idaho’s nickname is the Gem State, it seemed like the Idaho Cut would be a natural fit. It also would also be a wonderful and proper way to permanently honor Q’s legacy. With one of my nephews, Aaron Quincy Howell, and two of my nieces (who are sisters), Wendy Burdick and Cheri Henney, we assembled into a team. We reasoned that getting the help of a government relations expert would be wise. After a few months of search, Benn Brocksome agreed to take on our project. With the sponsorship of two Idaho state senators, Lori Den Hartog and Megan Blanksma, a bill was introduced to the 2022 Idaho legislative session. After committee meetings and a Senate vote, it passed the Senate by a 32-0 vote with three absences. It later passed the House of Representatives 68-1 with one absence. On March 24, 2022, the governor signed the bill into state law, and the Idaho Cut was declared to be the official state cut for faceted gemstones.

We were grateful to Allan Beck, one of Quincy’s former students, who faceted an Idaho Cut that we passed around during the legislative process. In a legislative committee meeting, a representative asked, “Was Quincy a rich man?” Yes, I thought, he was rich in wisdom, candor, love, and integrity. Money was not part of that equation. He faceted because he loved the artform and made enough to perpetuate his craft, nothing more. Ever practical and modest, if he were alive today and learned of his Idaho Cut becoming an Idaho state symbol, he most likely would look to my mother and say, “All this fuss over me, Tej?”

The Idaho Cut can now be not only appreciated but faceted by future generations of artists, as its diagram exists in the public domain, where it belongs. Anyone can show the diagram to a jeweler and request that a gemstone be an Idaho Cut. In most cases this can be done affordably, depending on the type of stone. Local faceting gem clubs also may recommend individuals who can facet a stone.

To further promote education and understanding, our family developed TheIdahoCut.com, a non-commercial website where more can be learned about the Idaho Cut and Q. We hope to assemble his faceted gemstones in a permanent museum-quality public display, where future generations of Idahoans and other visitors can enjoy and appreciate the gift of beauty and excellence that Quincy Douglas Howell has given us all. As for me, I feel like the story of my father’s life is still being written.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

Comments are closed.