No products in the cart.

The Trailing Begins

“We Might Have a Festival Here”

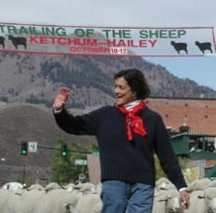

By Diane Josephy Peavey

Photos by Carol Waller

In 1982, I gave up a professional life in Washington, D.C., to spend time on a remote sheep and cattle ranch in the Little Wood River Valley. The area was, and still is, a ranching landscape just over the ridgeline from the resort communities of Sun Valley, Ketchum, and Hailey. For years, I had worked on political issues in our nation’s capital, and the ranch’s owner, John Peavey, was an Idaho state senator with whom I shared political interests when he persuaded me to make the move “for the summer.” But there was more. Since a very young age, my favorite food has been lamb. As an adult, whenever I returned to visit my parents, my mother would be waiting with a plate of sizzling lamb chops. She never forgot. How could I not fall for a sheep (and cattle) rancher who could offer me a lifetime of lamb chops, with a little politics on the side?

By the early 1990s and now married to John, I had learned enough to know that the traditional ranching families of which I had become a member and the growing populations of neighbors in town, where we lived in winter, both faced new challenges. These groups, the newcomers and the sheep families, were in for some serious lessons in sharing and working together.

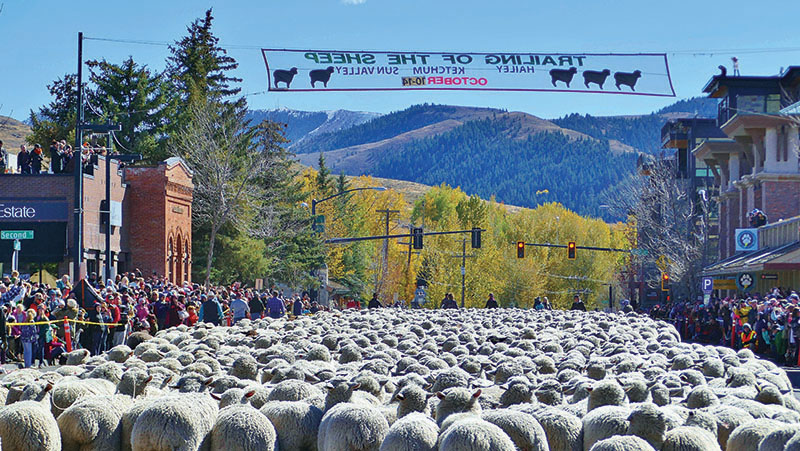

In many ways, when this year’s Trailing of the Sheep Festival, from October 5-9, celebrates twenty-six years of herding sheep down Ketchum’s Main Street in front of as many as twenty-five thousand cheering spectators, it will honor not only ranching traditions one hundred and fifty years old in Idaho, but also the willingness of our communities to make compromises that have allowed us to thrive together.

The first serious test of whether we could do that concerned the trail that had been used for years by sheep families to move their flocks north in the spring and south in the fall. The ranchers still held their traditional rights to the land but after several discussions, everyone seemed to agree that the trail should be shared with hikers, bikers, rollerbladers, and others. Asphalt for these activities was laid over the dirt path through the populated valley, which barely fazed the sheep, who trotted along happily with no more rough twigs underfoot. Life was good, if a bit more congested for the ranchers with so many new recreationists.

But then the calls began, at all times of the day and night.

“Get YOUR sheep off OUR bike path,” voices threatened, pleaded, even wept into the phone. Mostly, they were very angry. “The sheep droppings are all over my bike tires (or rollerblades or running shoes). How could you let this happen? My expensive hiking boots are ruined. Get those animals off our bike path!”

For days, the phone rang constantly with the same requests, or threats, until my husband did as he always does, and suggested we should meet these people and tell our story. John loves to explain what often seems unexplainable—and he does it well. But at this moment, we were under siege for grazing our sheep on land we’d used for years. To make matters worse, John was running for re-election to the Idaho Senate, and these calls were definitely not a part of his campaign strategy. Nonetheless, he followed through with his plan to put an ad in the local paper and invite any and all in the community to a local café at six on the same October morning that the sheep would be moving south along the bike path.

We met at a ranchers’ café in Ketchum, and as promised, he bought coffee all around and gave a history of sheep ranching in this part of Idaho. He then urged attendees to put on their jackets and gloves and walk with him for a while among the sheep, moving them south in the tall grasses. The very presence of people near or on the asphalt would keep the sheep and their droppings away from the new trail. That first year, about fifteen people showed up for coffee and herding. Even in the frigid morning air, they loved John’s sheep-ranching stories and were happy to be sheepherders for a few hours.

Chef Sean Temple conducts a lamb-cooking class during the festival.

Sheep cookies.

Oinkari Basque Dancers.

John Balderson does a sheep-shearing demonstration.

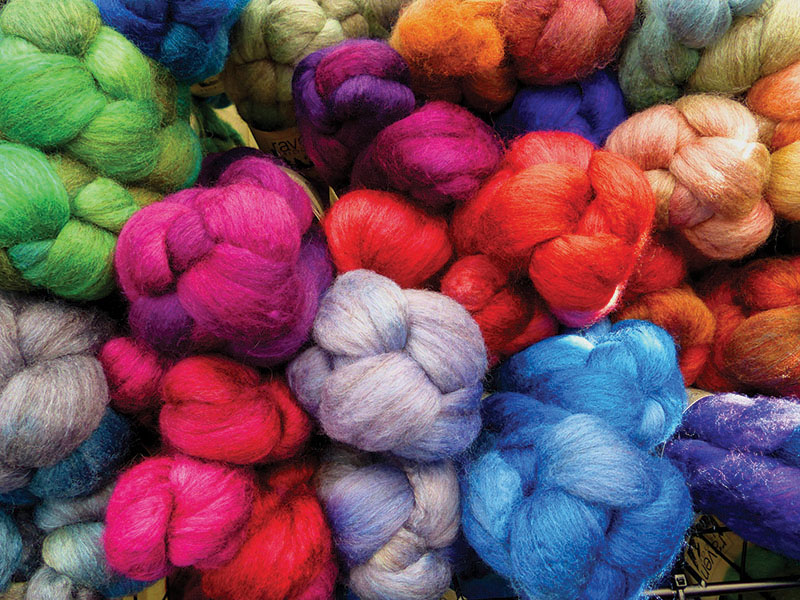

Colorful woolen yarn.

Spinning wool.

Basque dancers during the parade.

Peruvian musicians perform.

A Polish Highlander plays for the sheep.

Young Peruvian dancer.

Sheep fill Main Street of Ketchum during the parade.

A wall of wool in town.

Sheep dog trials during the festival.

Cute and curious.

Herder with sheep near a bridge.

Sheep fill the hillside.

Herders, dogs, and horses trail the sheep.

The next year, the numbers tripled, and they continued to grow every year after that. Families came out for the day, parents brought children after school, and some teachers called to see if next year they could bring their students to walk behind the sheep. John continued to tell ranch stories and answer questions, and the trailing of the sheep over the bike path became a favorite local activity each fall. But no one had any idea that this was only the beginning

Meanwhile, John was re-elected and remained our senator until he retired several terms later. In 1995, at a local gallery opening of paintings and photography of sheep, he was asked to give a short talk about these animals and their life cycles. To my surprise, he invited the guests at the event to join us the next morning on the corner of Saddle Road and Highway 75. There they could watch our sheep, the herders, and our family come through the area moving a band of one thousand to fifteen hundred ewes. We were trailing the animals to winter pastures to the south but only on Ketchum backroads, to avoid the morning traffic. We would be in a perfect viewing place, he assured everyone.

The next day, most of the guests showed up at first light to cheer and wave and hold back the traffic as the sheep passed by. John and I silently prayed that the sheep wouldn’t be spooked by the enthusiastic crowd, but all was well and the spectators got to see and photograph the animals at their best.

Later that day, I followed the procession south in the car of a friend, Carol Waller, who was then the Executive Director of the Sun Valley/Ketchum Chamber of Commerce. She had come out to view the sheep with us and now we discussed the crowds along the route and their enthusiasm. What I most remember from the conversation were Carol’s words. “You know Diane,” she said, “I think we might have a festival here.” This sentence flew around the car, bouncing off doors and windows, and my mind kept reaching out to grab at it. “You think we might have a festival here?” I repeated in disbelief and wonder.

As this thought settled in over the next few days, my mind flew back to Washington, D.C., where I had lived most of my life and where I had counted the days until the Smithsonian Folklife Fair took over a large area of the Washington Mall for several weeks every summer. It was a folk festival like the one Carol was suggesting. Foods, crafts, work skills, music, and dancing from all over the United States were on display. I spent hours at the booths, tasting samples of jams from West Virginia and jerky from Montana, but I always returned to the center stage when the Oinkari musicians and dancers from Boise performed. I confess, forty years ago when the idea of moving to a ranch in Idaho arose, it was a bit scary but I was calmed, even excited, by the prospect of being in the same state with the Oinkari Basques I had seen in Washington. I thought of them as family, although they didn’t know it.

That’s why even though I might have been a little slow on the uptake when Carol Waller suggested in the car that the trailing of the sheep could be a festival, my first thought and comment to her was, “Yes, and let’s include the Oinkaris.” The rest of the ride was filled with excitement, as we discussed the possibilities of a festival. We’d hold it in the fall, we decided. It would center around three core events: storytelling—listening to, remembering, and recording sheep stories of yesterday and today; a full day’s fair with dance and musical performances by three groups associated with our sheep industry over the years, the Basque Oinkaris, Boise Scottish Highlanders, and Peruvian musicians and dancers; and a sheep parade honoring the family, herders, and fifteen hundred sheep moving through town and south to warmer climates.

We decided the fair should have sheep-shearing demonstrations, vendors with wool and lamb-themed crafts, and a stage for the Basques, Peruvians, Scots, and perhaps other musicians and dancers to perform. There should also be lots of delicious lamb to sample.

It was Carol who followed up on these thoughts by suggesting a parade of sheep down Ketchum’s Main Street with ranch families and herders behind to keep them moving easily and safely toward the county trail to desert pastures after a summer in the high mountains. “Fifteen hundred animals running through town?” I questioned. She countered, “All those sheep at once would be breathtaking.” I agreed but decided to check that out with my husband, who frowned initially, as did most of the other sheep ranchers. Eventually, though, he and the others took it on and it became the great event it is today.

At the first festival, the crowds were relatively small but soon visitors from across the country began to arrive in surprising numbers, as the event grew into a part of our history. Most important of all this was our determination to gather and save the stories of our lives as ranchers, herders, parents, cooks, cowboys, camp-tenders, and more. Even though the spectacle of sheep running down Main Street is always met with thunderous applause and can be riotous and heart-stopping, and despite the attractions of music and food, the Trailing is about the stories and history of herders and ranchers—men and women who come from around the world and inspire us with their tales of bravery and conviction, losses, rescues, tragedies, and deep commitment to the sheep and the land.

We hear stories of the dogs who are always at the side of the working men and women, and of herding sheep across miles of empty country on horseback. Stories of quiet days on quiet lands, then of storms and getting lost, of finding the way back, of animals and men moving together though these magnificent yet lonely landscapes. Some of these stories pass from generation to generation, of life in sheep camps, baking sheepherder bread, wrapping up in wool clothing that saves lives in howling winter storms, rescuing a lost lamb. There are days of hope and moments of beauty, and also days of loss and untold hardships, even of quitting and leaving for home. But looking back, these men and women often tell us, they would have it no other way.

We have listened to many such stories over the past quarter-century and they are all archived and accessible at the Ketchum Community Library. This is the festival’s lasting legacy. Many herders and sheep ranchers, men and women, have tears in their eyes when they tell us the stories of their lives. Those tears seem to be wrapped inside each recording and archived in the library for all to experience. We have much to learn from these stories, which can help us to live more bravely and more meaningfully.

Now in October, before the sheep are led south again this fall, we will listen to stories and music, watch dog trials, and eat lots of delicious lamb dishes. The festival will not only celebrate life and hard work but it will be a send-off for the herders, dogs, and sheep as they head toward a new winter in warm landscapes in the continuing cycle of their lives.

The twenty-sixth annual Trailing of the Sheep Festival, which will be held on October 5-9 in Ketchum, has been recognized by msn.com as one of the “Top Ten Fall Festivals in the World.” There will be nonstop activities in multiple venues, including history, folk arts, a sheep folklife fair, lamb culinary offerings, a wool festival with classes and workshops, music, dance, storytelling, championship sheepdog trials, and the always entertaining Big Sheep Parade, which now involves as many as eighteen hundred sheep hoofing it down Ketchum’s Main Street. For a detailed schedule, tickets, and lodging information, visit www.trailingofthesheep.org.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

Comments are closed.