No products in the cart.

There’s Kirsten

Museum Stories

By Mary Reed

A few fourth-grade boys on a school field trip in 1988 to Moscow’s McConnell Mansion left the group on the second floor and opened a closet door to an exciting discovery. I was then the new director of Latah County Historical Society and moments earlier I had nervously greeted the children in the hallway of the 1886 mansion. I was nervous because my academic background in history would be of little help in handling school field trips. The first thing I did was tell the students the house was a hundred years old but that didn’t work—none of them cared. I stumbled on, taking them upstairs, where the breakaway boys came across a group of manikins in the closet. They rushed back, calling to the other kids, “Come see the naked ladies!” I threw myself against the closet door and sharply told them to keep away.

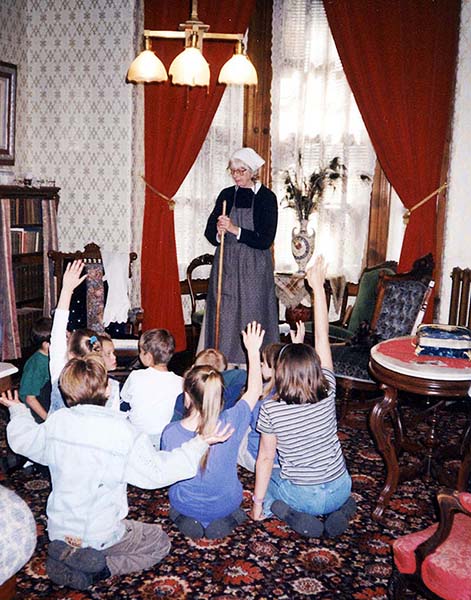

There had to be a better way. It took me a while to find a solution: I created the character of Kirsten Anderson, a hired girl from Sweden. Wearing a simple costume of an apron and headscarf and holding a feather duster, I greeted children at the door and led them into the parlor. There I complained about the housecleaning chores, the fussy owner Mrs. Adair, and the lazy hired man Jim. I praised the features of the new carpet sweeper and the Edison phonograph. In the kitchen, I rang up the operator on the new wooden wall phone for a short chat.

I wasn’t the only one talking. The kids eagerly engaged with Kirsten, talking about modern electric vacuum cleaners, CD players, and touch-tone telephones. To their great delight, I expressed how astounded I was. Their positive response to this performance taught me that people’s lives, technology, and the opportunity to interact were key ingredients in educating and engaging audiences. Kirsten had an additional benefit, as many children returned to the museum, bringing their friends and parents. Kids believed in her. I’d sometimes see them on a sidewalk and they’d tell their parents, “There’s Kirsten!”

When I began my museum career in 1983, most small museums had much in common. Their founders had diligently collected and preserved materials relating to the early pioneer years. They crowded their collections and staff into basements or vacant public buildings and houses. They continually struggled to pay bills, recruit volunteers, and keep the doors open for visitors. Storage space was a problem that worsened as the public eagerly brought in donations. The work of documenting and conserving these materials was overwhelming. Most museums did not have a collections policy and would accept almost anything, including materials unrelated to their community’s history.

Museums faced other challenges, too. Visitors were discouraged by old-style exhibits in cluttered rooms that often contained photographs with lengthy labels and shelves of miscellaneous objects that ranged from typewriters to salt-and-pepper shakers. Like my fourth-graders, people wanted to know the stories and interact with the exhibits.

New methods of presenting information were emerging: smaller and more concise labels, creative visual exhibits, and interactive stimulation that included hands-on activities. Most visitors were not interested in simply looking at artifacts and photographs. As one youngster put it, “I don’t want my grandfather’s museum.” It was time to move on.

The 1931 Parlor Gallery after renovation. Historical Museum at St. Gertrude.

Replica of the original attic museum. Historical Museum at St. Gertrude.

Mary dressed as Kirsten Anderson. Latah County Historical Society.

Students converse with Mary as Kirsten. Latah County Historical Society.

Exhibits before renovation. Historical Museum at St. Gertrude.

Young visitor at the Polly Bemis display. Historical Museum at St. Gertrude.

Prairie Gallery after its redesign. Historical Museum at St. Gertrude.

Sawyer's cabin exhibit at Bradbury Memorial Museum in Pierce. Mary Reed.

Keith Petersen with daughter Usha. Historical Museum at St. Gertrude.

Welcome panel. Historical Museum at St. Gertrude.

During my tenure at the Latah County Historical Society, I also worked with museums around the state, an endeavor that would continue after I retired in 2006. The Idaho Association of Museums’ workshops and annual meetings provided healthy exchanges of ideas, resources, and skills. I put this knowledge and experience into practice during the bicentennial commemoration of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Idaho was a major player during this nationwide event. Its congressional delegation provided generous funding to the governor’s Lewis and Clark Trail Committee, which planned and funded multi-faceted commemorative activities and projects. Conscious of the projected large number of tourists coming to Idaho, the committee supported projects to improve museums’ facilities and enhance visitors’ experiences through new exhibits and projects.

The Trail Committee’s Museum Initiative provided nine hundred thousand dollars to be divided among eleven museums over a six-year period. In January 2000, I joined its consulting team. The grant process began with each trail museum first assessing its needs and submitting proposals. Then the team visited each site to discuss its projects and suggest ways to meet their goals. Changes were substantial. New computers, lighting, exhibit cases, storage space, security systems, computers and printers, updated telephone systems, websites, and renovated restrooms now welcomed visitors. One museum worker described the changes as bringing the facility out of the Dark Ages.

After this project was completed, I continued to work as a consultant. With funding from the Governor’s Committee and sponsorship from the Idaho Heritage Trust, I received a grant to assist five museums in developing new exhibits. It was a partnership with each museum’s board and staff, who usually were all volunteers. The grant had three components. First, I visited each museum at least six times to discuss ideas, priorities, problems, and progress. Second, the grant provided financial help for exhibit materials. Third, the staff and volunteers physically did the work under my direction and distribution of resources. Often, a consultant offers only advice but this project provided training and assistance to help museum staff and volunteers carry out their own projects.

In each case, we developed a collections policy that allowed museums to control what they would accept and to educate people about the new rules. The policy not only emphasized priorities, it also relieved pressure on the staff to accept items. We also worked on how to interpret and present an area’s history. These museums had rich collections but the interpretations and stories of the materials were minimal or missing. We developed major themes and topics and then selected materials to support these stories: photographs, documents, personal accounts, and so forth. This often involved moving unrelated objects into storage.

Another focus was on exhibit design and installation. We discussed ways to describe how objects were made and used, their history, and ownership. I stressed that concise and interactive labels had to be produced. These labels would probe events, ask questions, and even introduce controversial issues. Brochures and exhibit guides could provide additional information. Design was an important component, including use of color, textures, and three-dimensional spacing. My visits prompted lively discussions and, together, we found creative ways to carry out projects and improve the museums. I provided advice and resources but the final decisions were theirs.

I’ll give two examples of changes this partnership accomplished:

The Lemhi County Historical Museum in Salmon has a rich and varied collection of artifacts and it has strong leadership. On my first visit, I found that visitors coming into the entrance faced a bench with stern warnings about what was not allowed: no photos, do not touch artifacts, no food allowed. This was quickly fixed by removing the barrier and adopting signage that welcomed visitors.

Our next challenge was creating more exhibit space. A massive collection of Chinese artifacts that had come from a donor years ago filled an entire wall. These objects were interesting and valuable but they took up a large amount of space and had no connection to the museum’s mission of collecting and preserving Lemhi County’s history. Our solution was to keep a small number of them on exhibit and store the rest.

We then turned to selecting the most important stories to highlight. This decision was not difficult. The Lemhi Shoshone, who once lived freely in the valley, had lost their lands and livelihood to white settlers. An 1875 treaty created a small reservation controlled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. But tensions mounted and in 1909 the tribe was forced to move from its homeland to the Fort Hall Reservation. Fortunately, the county historical society had preserved their presence in a large collection of photos, documents, reminiscences, and artifacts. Many of these artifacts had belonged to the family of Chief Tendoy and were beautifully crafted with beadwork. The exhibit and history of the Lemhi Shoshone is now a highlight of the museum’s exhibits as well as an important narrative on cultural differences, prejudice, conflicting attitudes, and mistreatment, as well as friendship and respect among members of the two groups.

In Pierce, the J. Howard Bradbury Memorial Museum contained an abundant collection of materials relating to the prominence of mining and lumbering in the area. Idaho as we know it started here, with the discovery of gold in 1860. The challenge was how to select the best way to connect the history from that early mining period to more modern lumbering operations. The museum personnel selected four characters to highlight. E.D. Pierce was the prospector who first struck gold on the Clearwater River in 1860. Nez Perce Chief Timothy’s daughter Jane Silcott led the Pierce party to Orofino Creek at age eighteen and later operated a ferry with her husband that went across the Clearwater River. Judge Israel Cowen was a miner who held several local and state offices, including postmaster, which meant he routinely walked a ten-mile route. And Thomas Kinney was a lumberjack who came to Pierce to supervise the building and operations of the Headquarters Camp. He later became vice president of Potlatch Forests, Inc., in Lewiston.

We converted a nearby storage shed into a sawyer’s cabin with a bed and personal belongings, including a crosscut saw. The cabin’s interior included a panel illustrating the features of the saw and a description of how it worked. This setting added a personal and interesting perspective for visitors.

After I retired, I joined my husband, Keith Petersen, who was then the Idaho State Historian, on visits to small museums throughout Idaho. All had valuable collections of artifacts and materials central to the state’s history. There were also distinct differences in priorities, resources, and strategies for attracting and educating visitors. One museum in a rural part of Idaho complained of people who came by just to use the restrooms. They wanted to discuss ways to deter these people rather than how to engage them in learning about local history. On the opposite end of that spectrum, the National Oregon/California Trail Center in Montpelier welcomed visitors who often arrived in tour buses to use the restrooms. The staff had realized this was an opportunity to work with tour organizers to extend their customers’ time at the museum. They offered not only restrooms but also a café, a well-stocked gift store, and a variety of activities and exhibits. A major attraction there is the “Travelin’ West” experience, in which visitors become part of a pioneer wagon company headed west on a two thousand-mile journey along the Oregon/California Trail. Children have a special tour led by the wagon master. The center transformed its passersby into eager visitors.

The culmination of my consulting career was a challenging five-year project. A few miles from Cottonwood is the imposing structure of the Benedictine Monastery of St. Gertrude. Located on the Camas Prairie, it has a beautiful and peaceful pastoral setting for reflection. This is the home of nuns whose history stretches back to the sixth century in Switzerland. Over the decades these religious women faced challenges of plagues, poverty, and political upheavals. In 1882, three of the sisters left their cloistered convent in Switzerland to travel by train, boat, and transcontinental railroad to Oregon, where they hoped to establish a foundation. After a year of undergoing severe sicknesses and uncertainty about their futures, they found convents and schools in eastern Washington, first in Uniontown and then in Colton. In 1907, the sisters of the growing order moved into a small farmhouse in Cottonwood.

Sister Alfreda Elsensohn founded a museum at the monastery in 1931 as a teaching resource for their adjoining school. One of Idaho’s oldest museums, it began in an attic. In 1980, the monastery funded construction of the current building. Although the collections were on display, the stories remained largely untold. Among them was the remarkable account of the Benedictine nuns. In 2014, my husband Keith and Patty Miller, the director of Boise’s Basque Museum, met with the museum staff to discuss renovating the physical space and installing new exhibits. The first step and highest priority of the five-year plan was to tell the nuns’ story. Eager to be part of the project, I joined the team the next year. Much work lay ahead. Keith and I provided advice but the monastery’s professional team undertook most of the work.

Our goal was to create exhibits that were researched and designed well, using new ideas and technologies to bring these historic characters and events alive. A priority was space. Asian artifacts occupied a new addition that had been built exclusively for a donor’s collection [see “The Bamboo Jacket,” IDAHO magazine, July 2018]. Putting a large part of the artifacts into storage almost doubled the area for new exhibits. QR codes, flip books on reader rails, digital records, and videos added information while also saving space. We added authenticity to the exhibits by recycling doors from the monastery to serve as exhibit walls. Former altar rails held historic photographs and interpretive text.

Entering the museum, you’re now greeted by a photo panel of Prioress Mary Forman, accompanied by an invitation to follow the nuns’ journey. You meet Sister Johanna, one of the first three sisters who left Switzerland. She describes her thoughts on leaving: “Wednesday, September 26, 1882 was a sad day for those who were to exchange their dear convent home for a far off, unknown land and an uncertain existence.” The artifacts reveal the nuns’ simple and thrifty lives. Across the room, behind a section of the original altar rail, you see the kitchen exhibit where the sisters cooked and canned produce from their gardens. To the left, a photo of smiling nuns invites you to sit down and take a selfie. Sharing these photos with families and friends will be good publicity for the museum.

Some of those recycled monastery doors form a dividing wall in a larger space. Here is the story of the sisters’ outreach work: teaching at fourteen schools and working in three hospitals around Idaho. A photo of women relaxing in a campsite is actually the nuns no longer in habits and enjoying the relaxed rules from Vatican II. The last panel tells us about their work in Colombia, teaching and caring for children. In the center of the room are their printing press, gardening and kitchen implements, and a crimping machine that creates tiny pleats for coifs. A short video shows how it works. In these two rooms, the history has taken you from 1882 into the 21st Century. We wanted visitors to know that the nuns still contribute to the fabric of the region.

Walking onward, you enter the replica of Sister Alfreda’s attic museum. It’s filled with the eclectic items she gathered for her teaching career, including a mounted eagle. This exhibit encourages people to think of how museums have changed. Leaving the attic, you encounter some extraordinary characters. Polly Bemis, the Chinese woman who became the subject of books and a film, meets you with a smile. She left China at age sixteen and ran a ranch and large vegetable garden along the Salmon River with her husband Charlie. Buckskin Bill, a self-promoted frontiersman, shows off his handmade bow. Following the sound of music, you find Winnifred Rhoades Emmanuel at an organ console. She began playing for silent movies and then became a celebrated organist, playing in concerts and on radio broadcasts throughout the Pacific Northwest.

The tour continues with the history of the Nez Perce Tribe, Chinese miners, and ranching and farming on the prairie. At the farming exhibit, you watch how the fanning mill machine works to separate seeds, while a continuous video compares historic and modern agriculture on the Camas Prairie.

There are two stops left. Approaching the 1931 living room, you hear a familiar voice coming from the Philco tube radio. It is President Roosevelt broadcasting a fireside chat to help cheer and restore the nation’s confidence during the Great Depression. You pause at the children’s activity center, where everyone, adults included, can practice writing Chinese characters. Samples of incense, tea, and spices add olfactory information. A favorite dress-up activity for girls and boys is to become Polly Bemis or Buckskin Bill and a large mirror lets them admire the results. Your visit ends in the gift shop, browsing through books for adults and children as well as candles, soap, notecards, and other items. I recommend a jar or two of my favorite item: the monastery’s homemade raspberry jam.

Visitors’ glowing comments have validated these changes: the focus on people, technology, interactive opportunities, and visual and auditory stimulation have engaged and educated not only the museum-goers but also those who live and work at the monastery.

Museums today face great opportunities and challenges. The digital age creates new and quicker ways of reaching audiences. Facebook and other social media offer the public an easy way to connect with staff. Newsletters and announcements are posted online. Collections of artifacts, documents, and photographs can be digitized and easily accessed. Staff can also use the internet to research documents, newspapers, and other sources. Audiences can attend lectures and meetings through Zoom and similar software programs. But all these functions require skills to create digital access and train staff. Museums still face the familiar tasks of fundraising, recruiting volunteers, and maintaining facilities. Funding remains a major item because of competition from other organizations and the reluctance city and county officials often have to sustain or increase support. Fortunately, the Idaho Humanities Council, the Idaho Historical Society, the Heritage Trust, and other funding sources have been a reliable source of help through the decades for these organizations that collect, preserve and make available the materials and stories that are the basis of Idaho’s rich and complex history.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only