No products in the cart.

Death of the Forest Cabin

I’ve lived my whole life in Camas County, which is almost exactly the size of Rhode Island but has long had a population of around one thousand. The county’s single east-west valley has an elevation of about five thousand feet above sea level, while to the south are low mountains, and to the north are peaks that reach higher than ten thousand feet. Extremely cold winter temperatures (1990 saw an official low of fifty-two degrees below zero) and deep snow discourage everyone except the hardiest individuals from living here.

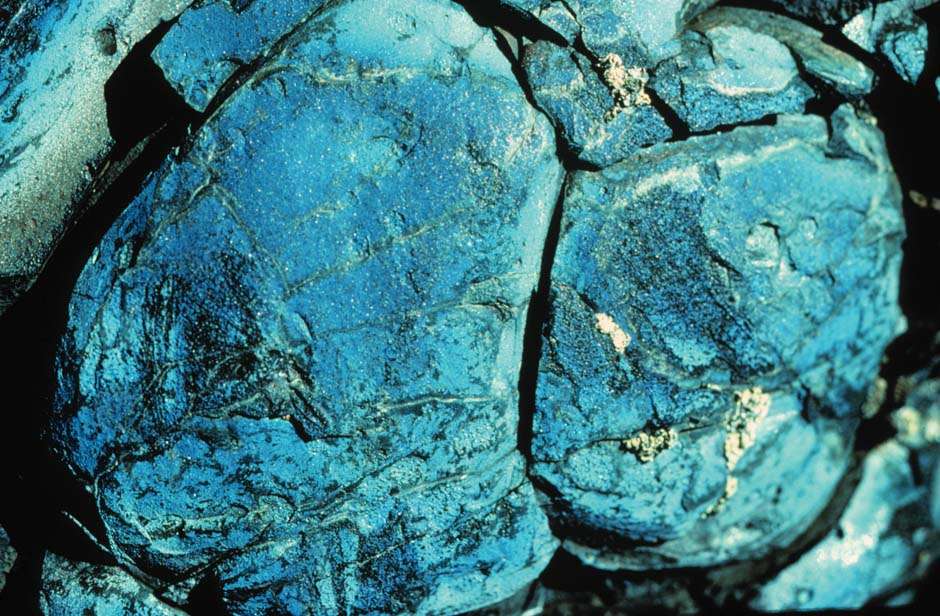

The farmers and ranchers who settled this area in the 1880s scratched out a living. Mining was a major effort and the remains of dozens of small operations—gold and silver mines, although lead and other trace minerals were present—can be found in all parts of the county. No major strikes were made, but some wealth was taken out of the earth. Many “prove-up” shacks were built as farming homesteads, and even in the highest mountains, every mine had some kind of shelter. A hard rock mining claim I own at 9,400 feet has a typical shack that housed miners early last century. Decades ago, the weight of ten or more feet of snow caused its collapse. Continue reading →

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only