No products in the cart.

It’s a Rod, Not a Pole

Talking the Talk

By Marcia McGreevy Lewis

Fly fishing? I didn’t think so. Then I met my beau, Chapin Henry, who coached me, and angling became our mutual obsession. In September we headed for Henrys Fork, also called the North Fork of the Snake River. “Fish take you to some beautiful places,” said he, a seasoned fly fisherman who has traveled the world to catch and release the wily trout.

Our destination from Seattle was Driggs, which meant that Willie Nelson CDs serenaded us as we carved our way through the pungent aroma of endless sagebrush. We rambled through “poke and plumbs,” as my fisherman calls them: “You poke your head out the window and you’re plumb out of town.”

We concluded that Montana has no private domain over open sky. Idaho’s dome is so vast that we saw the formation of a twister and battleship-grey clouds that poured nails of rain on the horizon. We stopped at Craters of the Moon National Monument: acres of black, pockmarked volcanic rock and cinder cones. Confirmation that we were in potato country arrived in the form of half-submerged potato sheds dotting the horizon. Split-rail fences, what the locals call “buck’n rail,” promised civilization and, sure enough, soon there were houses clustered under poplars. Then there was a slow-down sign and we entered Driggs. The house where we stayed afforded us the luxury of a daily nod to the four colossal peaks of the Tetons. Waking up to those stately mountains that pierce the clouds was something I’ll always remember.

Driggs authenticates its western heritage with log entryways that crown driveways, dilapidated buckboards that adorn many front yards, and potato vodka that’s local gold. Huckleberries (also golden) go for an average of ninety dollars per gallon. We ate with the cowboys at the local restaurant until we noticed a ’46 cherry-red truck toting a two-ton potato, and then we were at the drive-in.

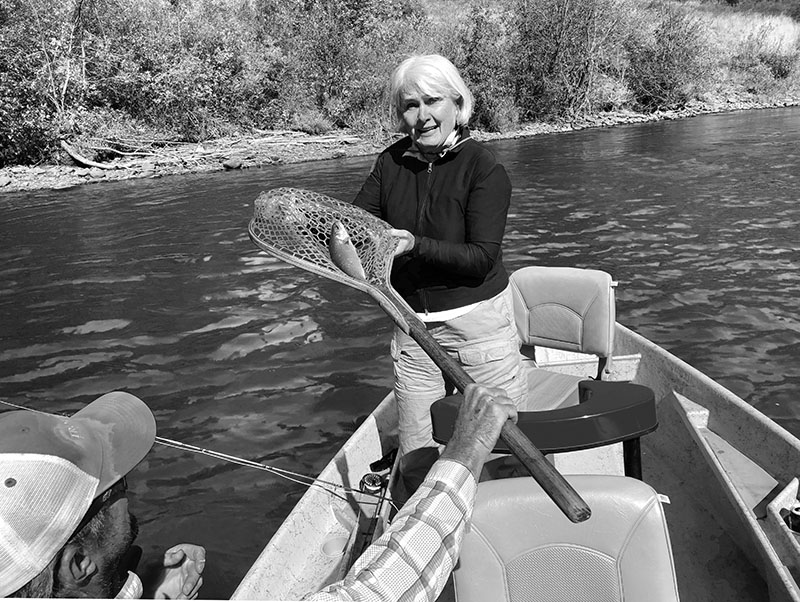

Marcia, undistracted by the scenery, nets a rainbow. Chapin Henry.

Guide Kevin Shulund displays a monstrous catch. Marcia McGreevy Lewis.

The patient angler. Marcia McGreevy Lewis.

Henry catches a prize trout. Marcia McGreevy Lewis.

When we journeyed to Mesa Falls in Idaho’s Targhee National Forest, we were sprayed by both thunderous falls and trickles. When we found a pocket-sized gurgle of

water at Big Springs, about nine miles northwest of Island Park, we were surprised to learn that this was the source of Henrys Fork. And, just as my partner predicted, Henrys Fork was beautiful: dramatic one moment as it gushed and swirled around rocks and snags of trees and then serene the next as it kissed the banks.

We floated the Snake for two days of fishing in ideal weather of sixty degrees with no wind. Our guide spied fins fluttering yards away and we cast. We caught, he unhooked. We were hungry, he served lunch. Who could not like fly fishing?

Our third day of fishing was on the Teton River, and it almost lost me Chapin as a fishing buddy. I forgot to cast. I couldn’t keep my eyes off the golden eagles and was ecstatic when we saw a moose. Sandhill cranes lined the shore, falcons streaked by, and on the riverside cliffs we found honeycombed nests of swallows that resembled oversized barnacles. I was further distracted by river otters that invaded the best fishing spot—of course they did. They fought for it. And a beaver in broad daylight. Beavers are nocturnal, but this one flopped his gigantic tail at us to warn us away from his territory. His lodge must have been pretty special if he was losing sleep over it.

Cottonwoods dominated the riverbanks, which were full of grasshoppers, making it clear why we were casting with “hoppers.”

Our guide changed the flies frequently and was diligent about greasing flies and leaders so they stayed afloat. I learned that dry flies, which float on the water, catch the majority

of the trout. Hoppers with droppers catch the rest. These are dry fly hoppers to which are attached nymphs or representations of insect larva that drop below the surface. Fly bodies ranged from white to pink to orange so I could spot them on the water. Underneath, all the flies were fuzzy, speckled, and gangly. My pink fly seemed to catch the most fish. I never speculated that I would have a thing going with pink bugs, but I do now.

Translucent blue dragonflies, stout geese, menacing turkey vultures, and substantial osprey streaked by. There was an ample supply of small bugs cavorting around on the surface of the water. They had laid their eggs in the river, unaware of how alluring they were to the trout.

Our goal was to catch rainbows with an average length from four to nineteen inches. There was little doubt that my companion would help us to do this, just as there was little doubt I would undermine the effort. But he is a very patient coach, just as the guide also proved to be, so I did land a few scrawny rainbows. I’ll take scrawny.

We were rod-rich and had brought an assortment of weights. Also in the tackle box were leaders or shorter fishing lines attached to the main lines to protect them against damage, and carefully constructed crane flies, imitators of the crane fly that was in season. Because the wind was down, my partner used mostly two- or three-weight rods. I caught rainbows on my five-weight, and that day we also caught about twenty-five cutthroat. My boyfriend has an artful cast that helped him to catch the largest rainbow of the season in this fishery at nineteen inches.

Meanwhile, I referred to my rod as a pole and got strikes that I called bites. This led to

a lesson in terminology that one gets strikes on rods, not bites on poles, and one needs to strip or pull in line, mend or take in slack, and set or jerk up the rod for strikes. Our drift boat launched from the put-in and departed from the take-out. We were fishing for browns, whitefish, rainbows, and cutthroats, which we found in the seam, on the edge, on a shelf or against a wall—all in the water. We spotted them in water that was green, brown, bubbly, flat, or nervous. Nervous? Yes, nervous—and don’t forget, it’s a rod, not a pole.

The mantra that began to run in my head was:

* Cast upstream for a long run.

* Let out the extra line I’ve stripped in.

* Mend upstream as soon as I cast, which means raising my line upstream from the fly. Make that mend look like it’s lifting over a watermelon.

* Point the rod tip toward the fly.

* Follow the foam.

* Be ready to set over my right shoulder when I get a strike.

With all that going through my head, my casts were imperfect, many trout nibbled before I set, and I would have stabbed that watermelon. I could have blamed all this on the wind if there were any.

The question I most frequently asked of our guide was how deep the water was. The second most-frequent question was how to make it back to the vehicle. Of course, our guide had arranged shuttle service, and so I thanked him for this scenic and successful river float, and my fly fisherman reserved space on his calendar for a return to the Teton.

If I can keep my eyes off the canyon walls, he might take me, but who doesn’t find intriguing the massive brown basalt columns that border one side of the canyon and the colossal white boulders that line the other? Until I return, Idaho will flow through my imagination like its exquisite rivers.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only

Comments are closed.