No products in the cart.

The Clearwater Bull

A Catch of a Lifetime

Story and Photos by Mark Mestaz

In mid-morning, when the sun peeked over the mountaintops and began to warm the shimmering Clearwater River, I finally felt it: a quick, firm bump at the end of my line. When I had begun my search downriver from Orofino for the elusive steelhead on that cold morning last October 30, it had been dark, not a soul stirring.

As I pulled up in my truck and quickly carried my spey rod and gear down to the river bank, excitement coursed through me. My wife, son, and daughter-in-law, who always enjoy coming with me on fishing excursions, were bundled up against the cold, and we all drank hot coffee to warm up. But every second is valuable while spey fishing and within a minute after we arrived, my coffee was finished and I was in the water.

The fog hovered above the river as I swung my first casts. In case you’re not familiar with spey fishing, it’s a form of fly fishing usually done with two-handed casts that can send large flies long distances. Any spey fisherman will understand me when I say it takes hundreds of casts before landing a fish.

Over the years, I’ve developed a love for this challenge. My timing must be perfect and the presentation flawless to put a floating or sinking fly right in front of a fish’s face when it’s so far away from me. It works my patience, but any chance I get, at any time of year, I spey fish the rivers of Idaho, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, and British Columbia.

Going to multiple rivers throughout different seasons helps me to see waters at different levels of flow, which gives me the advantage of understanding water structures in a river. On my next trip back to a particular river, I’ll know what’s underneath the water that the eye cannot see.

People may ask, “Why do spey fishermen spend so many hours, days, and weeks casting without catching a fish?” It may sound like insanity to do something over and over without any reward, especially because nowadays many of us are used to running through life as fast as we can towards our goals. But when we run too fast, we miss things.

Spey fishermen invest countless hours researching the rivers, water flows, time of year, spawning, floating flies, wet flies, sinking flies, and presentation techniques. When they finally get to the river, they may not catch a fish for a couple of years, depending in part on the amount of time they’ve invested.

However, they’re rewarded every time they re-enter the river and start casting, because their love of being in nature and the thrilling possibility of catching a fish on the swing are worth coming out empty-handed. When at last one day they feel the pull on the end of their line and reel in a fish, all that hard work pays off. Their measured footsteps through life have borne the fruit of their labor.

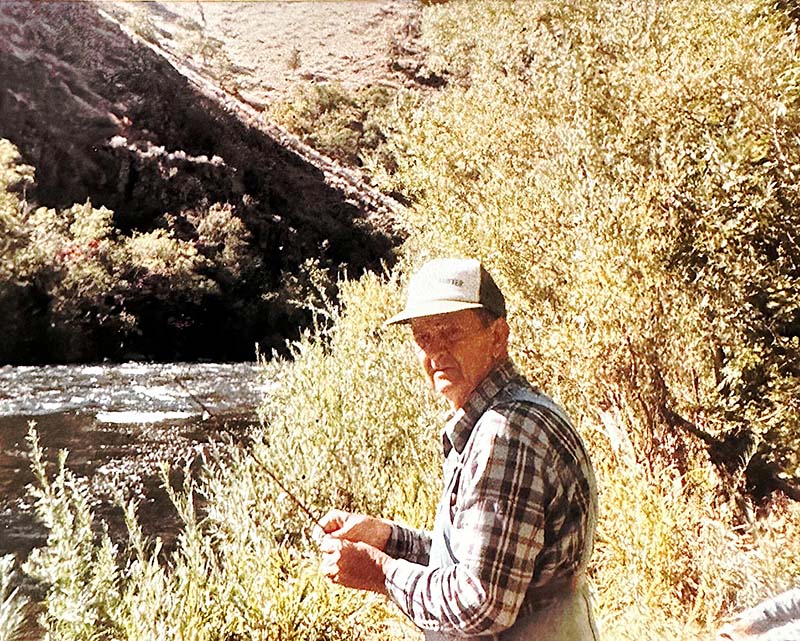

When I was young, my grandpa taught me to envision the thoughts and actions of a fish, as a hunter does with his prey. “You’re in the fish’s environment,” he told me, “and you have to think like it.” He knew fish are crafty creatures, and as I fished by his side, I watched and discovered their patterns.

I learned that they try to conserve energy to keep fat on them, and the big ones are especially good at following calm waters. They like to stop and rest by underwater boulders and hidden structures before continuing their journey upstream.

This morning I was casting directly at where I knew such boulders were in this particular spot on the Clearwater. I worked the river steadily and methodically, swinging one-hundred-foot casts that sent a black-and-blue sinking fly toward the submerged boulders. It was so bitterly cold that ice crystallized on my line.

When I finally felt that first bump on my line, I waited patiently for the right second to set the barbless hook. Many spey anglers lose steelhead because they have an overwhelming desire to set their hook quickly, before the fish has time to properly run.

But a little bit of patience goes a long way if one waits for the right moment. So I let the fish run my fly a little ways before I pumped the hook several times, trying to get it in deep. The fish was obviously big, because it didn’t sense what I was doing until it was too late. My hook was set.

“Now it’s about you and me,” I told the fish.

It was not only heavy but smart. I felt it staying down deep at the bottom of the river, where it moved violently and powerfully from boulder to boulder. I realized that the fish knew its environment and was comfortable in the deep columns of water and underwater boulder fields. It moved craftily in and out of runs, buckets, and riffles, trying to dislodge my barbless hook.

I continued to keep my tension tight on the rod, because I knew if there was any slack in the line, this fish would kick out the hook in an instant. Only a perfect execution of technique would bring in this formidable foe.

Downriver from Orofino on the Clearwater. Ken Lund.

Mark wish his spey fishing pole. Rosemary Mestaz.

The author's grandfather wets a line. Courtesy Mark Mestaz.

Mark's grandpa with a catch. Courtesy Mark Mestaz.

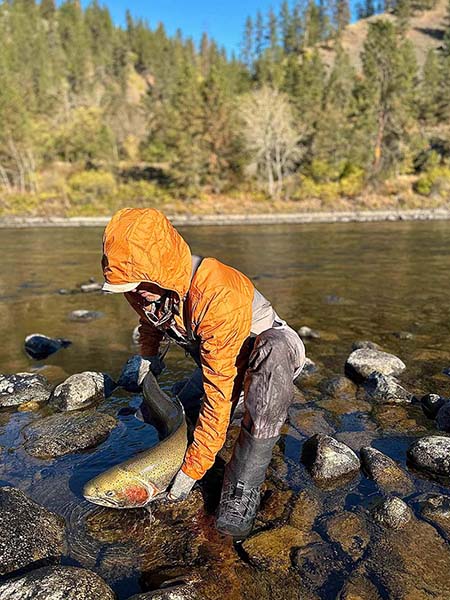

The author with his huge steelhead. Rosemary Mestaz.

Resting before release. Rosemary Mestaz.

Letting him go. Rosemary Mestaz.

As I continued to work the fish, it thrashed above the water, allowing me a glimpse of the beast at the end of my line. Up until then I had thought the fish on the line was probably a salmon, but that’s when I realized it was a huge steelhead—heavier than any I had hooked in all my years of fishing for big steelhead. During that next fifteen minutes of a hearty fight, I saw in my mind every thrash and tug of the fish.

The large bull used the currents and the flow of the water to his advantage and stayed across the river most of the fight. Only after I had wrestled with him a good while did he finally begin to move upriver, still staying near the opposite bank. I began to work the steelhead over to my side, knowing it would be a complicated task to get him near enough to the shore to be netted without losing him.

Finally, I got him to slowly start moving towards the center of the river and to pull above me. I took this opportunity to begin to put more tension in the line, to edge him toward the shallows of the river bank. The entire battle felt like a lifetime. It was a balance of strength and delicacy, of will and determination, in which my strategy became to use the steelhead’s weight and the river’s current to my advantage.

When the fish finally came closer to the shallows of the riverbank, I tried to back it down into a large net that my son Charlie was holding as he stood in the water. Charlie was approximately two-and-a-half feet deep in the water, but I could feel the steelhead refusing to come any closer to shore, and it took me several attempts to get the fish near the net.

On my final attempt, mustering all my strength and skill, I used the river’s current and the fish’s sheer mass to back it to the net. My son moved out deeper into the water to meet the big bull. With a quick, calculated move, he netted it.

Because of its size and weight, it was difficult for us to get the fish closer to the bank while still keeping it in the water. As a purist spey fisherman, I didn’t want to take the fish out of the water just then, because the length of the fight and the fish’s size meant it could have perished easily if it was out of the water too long.

My wife Rosemary and daughter-in-law Alexandria were on the bank taking pictures and video. Their mouths were wide open in shock as I measured the colossal fish in my net.

All those years I had spent learning from my grandfather and practicing my spey technique, all the time I had dedicated to learning rivers and chasing fish, had climaxed in this catch of a lifetime. At any moment, the steelhead could have broken free of my barbless hook, but I had brought it ashore.

In a case of wonderful timing, a Fish and Game conservation officer happened to arrive on the scene. He had parked and walked down to the riverbank to verify my license and barbless hook, but was just in time to bear witness to the massive fish and its proper release. He was as stunned as we all were that I had managed to reel it in.

The steelhead bull looked like he had stories to tell—he was a fighter and survivor. When steelhead are fresh from the ocean and begin traveling upriver, they have a bright chrome color for the first sixty or eighty miles. This one had shed his steely color for a striking green and yellow hue with a red streak along his side.

Understanding the importance of returning this beautiful fish to the river alive, I hurriedly took pictures of it and measured it in my net. He measured an astounding forty-six inches long, and his girth was twenty-six inches. I didn’t have the means to weigh him, but he felt to be about thirty pounds. For comparison, the current official catch-and-release state record for a steelhead is forty-one inches.

According to Clearwater Fisheries, the number of steelhead longer than forty inches was less than one percent of the run last year, but I will say that regardless of size, any steelhead is valuable to the spey fisherman who catches it.

I could tell our battle had exhausted this enormous steelhead and if I didn’t release him immediately, he would die. For a measurement to properly count towards the official catch-and-release state record, the fish must be laid flat for measurement. I had a decision to make: do I lay him out flat to make the measurement for the official record and risk killing him, or do I let him go?

The decision was easy. The preservation of this beautiful steelhead was far more important to me than any title. When I returned the fish to the water, I was worried because he didn’t move at first. I had to gently hold him for a while as water reentered his gills. After a couple minutes of this re-oxygenation, he revived and swam away powerfully.

I knew this steelhead had made several runs to the ocean in his lifetime and I had noticed that his adipose fin was cut, indicating he was a hatchery fish, which further impressed me. He was a testament to the hatchery program’s commitment and success in revitalizing our dwindling steelhead population. I extend my warmest thanks to the hatchery program for their efforts to give steelhead a chance to make their journey.

The steelhead bull I caught that day showcased all the effort and effectiveness of the program. The fish population desperately needs our hatchery programs and conservation efforts, especially as fishing grows in popularity and accessibility.

Though there are mixed opinions on fish hatchery programs and the fish they produce, I ask one question: if we did not have fish hatcheries, would we have any fish left in the rivers? Hatcheries aren’t a perfect system, but they have produced enough fish for river communities and fishing businesses to prosper amid the rising pressures on the rivers’ precious ecosystems.

With new developments in science and technology on the horizon, perhaps we can one day see the return of a wild, flourishing fish population without the assistance of hatcheries or dams. Until then, the hatcheries are critical.

Once the fish was safely released, the Fish and Game officer checked that my license and barbless hook were in order. Before leaving, he jokingly said, “Man, am I jealous of that fish!” I was happy to have him as an unexpected witness to testify to its astounding length and width. The officer said he usually did not patrol that section of the Clearwater River, but was thankful to have happened to stop by that day and see the Clearwater bull.

I love steelhead, because they’re powerful and survive adversity, coming off the deep, dark waters of the Pacific Ocean, where they roam for several years. By then, they’ve grown large and muscular. As they journey hundreds of miles up rivers, they remain incredibly elusive creatures. They begin to rip down and the striking chrome color of their skin changes. Bringing in a steelhead after the powerful fight that they put up is like winning the lottery. Each one is a diamond among the million river stones.

Seasoned steelhead fishermen know that the species’ dwindling population is a crisis, and we’re adamant about the need for their preservation. We follow an unspoken code of ethics, understanding that catching steelheads is an art rather than a sport.

Some will go to the extent of softening the soles of their boots to lessen the impact on the rocks in riverbeds. They will swing a fly in a variety of harsh conditions rather than using bait or trolling lures. They put effort into returning the fish alive to the river for both the preservation of the steelhead population and their natural habitat.

These steelheads need all of us to follow this silent code of ethics on the river, which hopefully will build back their population for future generations to enjoy the art of catching them, too.

On the other hand, catching and keeping fish for food is an important way of life for indigenous peoples and river communities. Fish have been an integral food source for humanity since the beginning of time. Unfortunately, as history has proven, humans have a tendency to take more than what they need. Therefore, whether a fisherman practices bobber doggin’, trolling, bait fishing, or spey—whether they catch-and-release or keep the fish—all of us must help to balance the wide use of our natural resources with protection of them for the future.

We are but visitors to the river system. Our concern for the residents of the river is how we show our appreciation for them. We must take responsibility now, because now is already yesterday and tomorrow is today.

When I was a young boy, these beliefs were instilled in me by my grandfather, who greatly influenced the development of my love for fishing and hunting. Now that I’m in my sixties, I realize that his wise teachings have stood the test of time—they’ve rung true for me ever since I was five years old. As a husband, father, grandfather, and veteran, I can attest to the truth of his words, which I’ve lived by all these years.

I’ve awakened to a bugle ringing throughout our barracks at two in the morning. Trained and mobilized to fight for my country on foreign soil, I survived and came to terms with the memories of those experiences, good and bad. Life is a delicate and precious journey, filled with moments of adversity that we all have to survive. Steelhead go through this journey, too.

When I plan fishing trips I search for seclusion, a world away from the everyday world, where I can immerse myself in thought and in the enticing pursuit of a fish. I welcome the opportunity to be enveloped in the breathtaking nature of mountains, trees, and rivers, and to have my patience stretched—and sometimes to be rewarded with a fish. I full-heartedly believe that life is not about how far we go, but rather the quality of our journey along the way.

I’ve learned that the quality of a fisherman comes from within and not from the equipment he or she uses. There are many different spey tips, scandi and skagit lines, rods, floating flies, and sinking flies fishermen can choose from—but if they lack dedication and patience, not even the highest-quality gear will matter.

When I’m not on the river, I prepare myself for the next opportunity to cast my line again. I research, and keep my body ready to endure eight- to ten-hour days in the water swinging rod tips of varying sizes. I want to feel strong when I put on my waders, so I work out during each week and maintain a healthy diet. My objective is twofold: to do what I love most for as long as I can and to pass on my knowledge to future generations.

Time has passed since the day I caught that Clearwater bull, but it has not left my mind. To me, it’s a metaphor for my grandpa’s teachings. It was the reward for relentless patience, dedication, and research. It was a fish my grandkids would remember Papa catching, an experience used by Papa to teach them about life. I hope my grandchildren will one day have the thrill of catching an even bigger one.

In the circle of life, seasons come and go, rivers rise and flow, and likewise my own life increasingly has appeared to be circular. I started fishing on the river with my grandpa when I was a small boy and then for many seasons I went from rivers to oceans and back, catching just about every species that crossed my path. In my latter days, I’ve returned to the river—just like the steelhead that swim from ocean to river, traveling there and back again.

I remember clearly the day Grandpa told me, “Porkchop (my nickname), fish make a journey. They go through hardships. They go all the way upriver to spawn and some go to die. They are either caught by predators or they survive. That’s the story of life. You’re going to go through adversity, but you must endure the journey of life. Pay attention, never give up the fight. Survive and endure like these fish.”

If you enjoyed this story, please consider supporting us with a SUBSCRIPTION to our print edition, delivered monthly to your doorstep.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

One Response to The Clearwater Bull

Michael Sawitz -

at

Much appreciated Mark. Thanks for verbalizing what many of us think but never speak.