No products in the cart.

The Cost of Charity

No Money, No Woodshed

By Khaliela Wright

I’m good with money. As a child, I was interested in both saving and investing. By the time I was twelve, I realized that I could get a silver dollar from the bank for just one dollar and then sell it to a silversmith for one-and-a-half dollars or two dollars. I also knew the value of waiting for a better price.

In my teen years, rather than pay full price for a new ski jacket at the beginning of the season, I’d wait for the after-Christmas sale.

As an adult, I taught my children these skills. In 2011, when my boys were working on their personal management merit badge for the Boy Scouts, we chose saving for a new TV as our family finance exercise. In February, we came up with a savings plan. In March and April, we combed through Consumer Reports to choose the best TV for our lifestyle. Once we made the selection, we waited before purchasing it. The wait was not so much to accumulate savings as it was for the price to come down. Nothing would compel me to buy our new TV before Black Friday.

In all the time that I’ve been participating in the consumer economy, never has my search for the best price been construed as accepting charity. But that changed this year, when I decided to replace the woodshed in our backyard in Potlatch. Several years earlier, heavy snow loads had led me to question the structural integrity of the shed’s roof, and a windstorm finally damaged it enough last winter to convince me it had to go. I started saving for a new shed while checking the websites of various home improvement stores. By June, I had the cash to purchase the kit, but lacked the skills to assemble it myself.

When my mother asked me what I wanted for my birthday, I said, “A shed.” I didn’t mean I wanted my parents to pay for it, but I wanted help building it. My mother pointed out that my father hated carpentry work.

“Why don’t you hire someone to do the work?” she said. “After all, that’s what we did when our deck needed replacement.”

“It’s taken me months to save enough money for the shed,” I replied. “I can’t afford to just hire someone.”

My parents reluctantly agreed to spend a day helping me build my new woodshed, and I thought I was in the clear. We arrived at the home improvement center early on a Saturday morning and paid $746.86 for a kit shed that claimed to include everything.

Not everything was included. The first thing I had to do was run out and buy a bag of screws for $7.43. Then, when all the pieces in the kit were assembled, the shed had no roof or floor.[/private]

The author’s old shed suffered damage to the roof. Khaliela Wright photo.

An Idaho shed in primary colors. Alan Levine photo.

Khaliela’s new shed kit lacked a roof to protect her firewood. Photo courtesy of Flyover Hangover.

An Idaho woodpile snowed under. A. Davey photo.

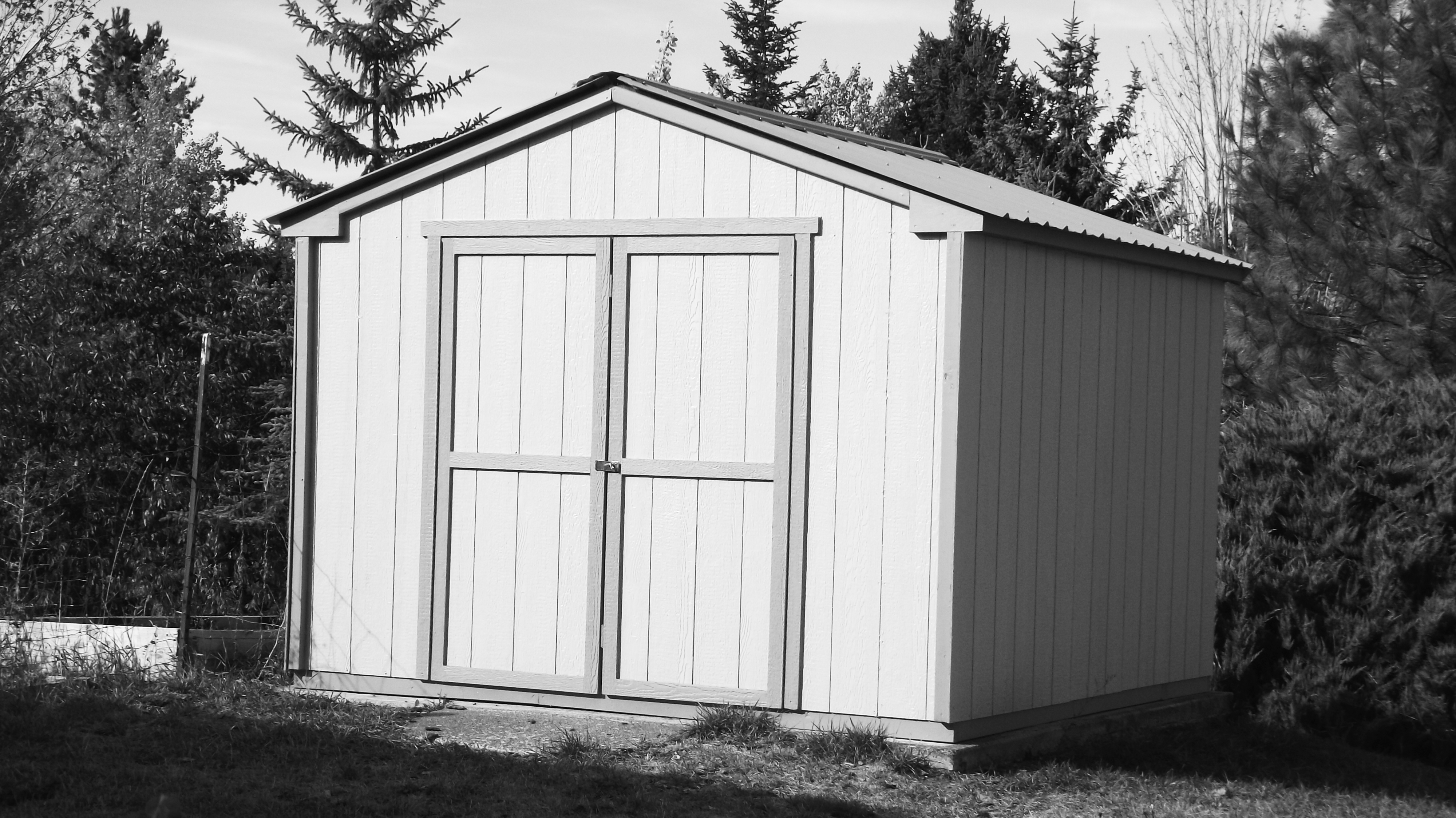

At last, the author’s new woodshed. Khaliela Wright photo.

The missing floor would not have been an issue, as the shed was being built on an existing cement pad, except that the first step in building the shed had been to assemble the floor joists. If I didn’t put down a floor, I would be forever tripping over the joists as I put wood in and took it out. The absence of the roof was a bit more perplexing. Without it, anything stored in the shed would be open to the elements, and from my perspective, the whole point was to protect stuff from the elements. So it was back to the hardware store for supplies again.

When we came home to install the floor and roof, my pocketbook was $219.95 lighter. After we finished the floor, we put plywood on the roof and covered it with roofing felt. When my parents bid me farewell, they said, “If you buy sheet metal for the roof, don’t call us. Hire someone to put it on.”

I did want a metal roof, and I also wanted to line the interior with plywood so that when the kids threw wood into the shed, it wouldn’t directly hit and possibly damage the siding, which had happened to the previous shed. But first I had to save the money to get these things done, as the absence of flooring and roofing in the shed kit had already put a bigger dent in my pocketbook than I was prepared for. Meanwhile, I painted the shed to match the house. I had plenty of trim color on hand, but needed to buy an extra gallon of blue, which cost another $37.10.

By August, I had enough money for the sheet metal and ridge cap. I paid $279.19 for the metal, brought it home and laid it out beside the shed. The problem was I still hadn’t found anyone to install it. Most of the contractors I spoke to said the job was too small for them to be interested in (the shed was only ten-by-ten feet), and the few contractors who were willing to work for me wanted fifty dollars an hour.

“I can’t afford that.”

“Then you should have gone to school so you could get a better job.”

Actually, I did go to school and earned not one, but two degrees. These men, mostly in their fifties, annoyed me. Maybe they didn’t have kids to feed or a mountain of student loans, and maybe that’s why they couldn’t comprehend that I was unable to pay them a wage more than five times what I earned per hour. It was clear I needed to be more creative in my search for labor.

I turned to the Idaho Department of Labor, figuring if I couldn’t afford to hire a working man, perhaps I could hire an unemployed one. I was willing to fill out the necessary paperwork and pay the taxes if I could hire a man for a day at $15 an hour, but I soon discovered it isn’t allowed. Dave Darrow, manager at the Moscow office, explained that state law prohibits people from using the Department of Labor to hire someone on a short-term, temporary basis. Only businesses offering long-term employment may use the department to hire workers, and if a man were to choose to work for me for a day or two, he would be breaking the law and could lose his unemployment benefits.

By now it was September, and the weather was starting to turn. Rain was in the air. I needed to get a roof on the shed before winter, and was beginning to get desperate. I turned to a non-governmental group that helps people build economical homes, but was informed that the going rate for people who used their services was forty dollars an hour. The woman I spoke to was quick to point out that the price was less than that of local contractors. But it was still four times more than I made per hour. In Latah County, the average cost of such a home is $100,000, but a main reason for this relatively low price is that the purchasers provide a good deal of the labor.

My next phone call was to an organization that aids the poor. After looking around, this group found a man who was willing to work for “charity.” When the man arrived, he informed me that since this was “a charity case” he would charge only thirty dollars per hour, but he needed a minimum price of one thousand dollars for the job.

“There had to be at least some money in it for me,” he said.

As we stood in front of the half-finished shed, I thanked him and sent him on

his way.

It seemed that I couldn’t even afford charity—which, according to some people in the community, appeared to be the equivalent of paying thirty dollars an hour.

I didn’t contact local churches. In 2007, I had approached two churches for assistance with a different project but in both cases had been told, “If you didn’t want to suffer hardship, you shouldn’t have gotten divorced.”

I moped back indoors and called my parents. The last weekend in September, they came down and helped me put the sheet metal on the roof to protect it from the impending rain. But to add the plywood lining to protect the shed’s interior, I was again told to hire someone.

I began frequenting the contractor’s desk at the hardware stores, trying to locate anyone working in construction who might be willing to do a little extra work on the side. In this way, I learned that while the contractors said they wanted fifty dollars per hour for the work, the men who were sent out to do the work were being paid only ten dollars an hour. I offered several of these men twenty dollars an hour to do they job but they declined, explaining that they would be fired if they were caught moonlighting, not to mention that they could face legal ramifications for undercutting the boss’s price.

By the end of October, I had begun giving a coworker named Armando covetous glances when I saw him at the office. I had already spent $126.41 for the plywood, which was leaning against the wall of the shed, waiting to be installed. What I needed was a man to work for a reasonable price, someone willing to work under the table. What I needed was a day laborer.

I knew that Pasco, Washington had hiring sites where a person could hire a man for a day’s work, but didn’t know of any such place in Idaho. My understanding was that a number of these temporary workers were Hispanic, and I feared being viewed as a racist if I were to approach Armando at work and say, “Do you know where I could hire a day laborer?” In the end, I remained silent.

By this time, I had spent so much money building the woodshed that I couldn’t afford the wood to fill it. And the sorry truth was that after spending a total of $1,416.94 (the equivalent of an entire month’s salary), the shed still wasn’t finished. I put the flannel sheets on the beds in the house. I added blankets and the flannel comforters. As the weather continued to cool, I supplemented the existing mound of bedding with quilts. By November, it was cold enough that we were wearing our coats inside the house.

On the weekend before Thanksgiving, an unexpected turn of events left me feeling hopeful that I would finally get the job done. I was at the gas station when I overheard a conversation between two men in front of me.

“Thanks for the ride home from work,” one of the men was saying. “I don’t know where I’ll get the money to have that broken-down vehicle fixed.”

“Excuse me, I’m looking for a man to do some work,” I butted in. “Would you happen to have any carpentry skills?

He said he did, and he could be at my home at noon on Sunday. I gave him my address and agreed to pay twenty dollars an hour.

He never arrived.

At 12:20 p.m., I went out to the shed, determined to do it myself. I did my best. My best wasn’t very good. Afterwards, I went inside and cried. Despite working full-time, it seemed I was unable to afford something as simple as heat, or even to afford the cost of charity. [/private]

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Purchase Only

Purchase Only