No products in the cart.

An Idaho Love to the End

By William Studebaker

Nearly seven months have passed since Dad died, and now a white box about 11” x 5” is squeezed between books on the bottom shelf of my bookcase. For Dad, that’s borderline ignobility. To be as a book or a bookend, well, if he knew, he’d grind his silica.

You see, he can’t turn over in his grave. He’s in that box. He’s been cremated, and a cremated person, as the mortician explained to me, isn’t really ash; rather he’s silica.

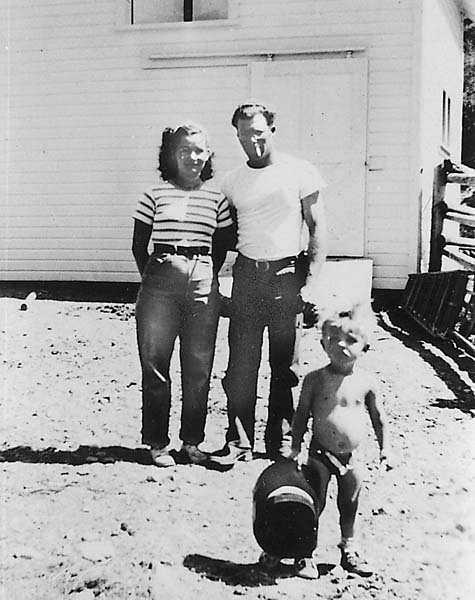

The author's parents at their happiest, living in Yellow Jacket. Photo courtesy of William Studebaker.

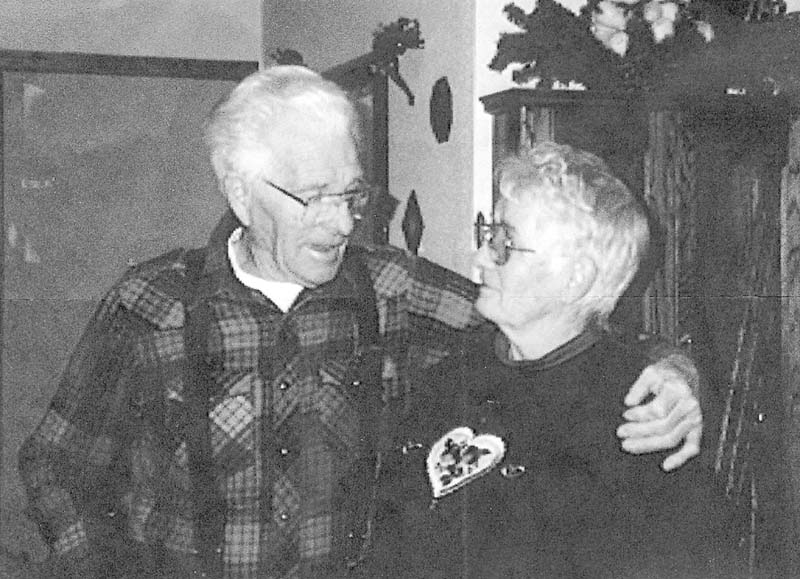

At their sixtieth wedding anniversary. Photo courtesy of William Studebaker.

Mom’s been living alone since Dad died. She’s taken widowhood in full stride. I suppose there must have been lonely hours, but she scrubbed the house. She washed all the curtains. She cleaned the car. She tidied up the yard, and she kept me and my sister busy reaching for and pounding on what she could not. It’s been grand because Penny and I thought she might fall into depression or trip over grief.

For the last several years, Dad didn’t like to get more than a short gallop from home. Now Mom’s able to jump in her car, zoom to Payette and visit her brother (who’s in a care center) and sister-in-law whenever she wants. Now that’s a joy. That’s as much fun as playing bingo or pinochle at the senior center.

Senior center! You’ve got to be kidding me. I never thought my mother would be out socializing, partying it up, going out for lunch, or buying raffle tickets. She’s even jumped on the bus and spent a senior citizen’s evening in Jackpot, Nevada.

There’s an irony there. Mom hasn’t always had so much company. During his last two and half years Dad consumed all of Mom’s time and energy with his peculiar brand of insane dying. Before that it was Idaho that consumed both their time. You see Idaho fit Dad. Idaho has a lot of space, and Dad needed a lot of space. He spent years in the Middle Fork of the Salmon River country. He ranched on the North Fork of the Salmon and on the Lemhi River. He had a yearning to do his own thing. That’s something Idahoans understand. Just drive around. Drive Highway 95 or Highway 93 top to bottom and you’ll see what I mean. You’ll see places like Dad’s place—where he’d fix his own cars, weld his own trailers, train his own horses, split his own wood, or make tire-swings. He even built the houses in which we lived.

He was neat. He kept things in rows and the grass mowed. The garden was always weed-free.

For Mom there wasn’t much company. She followed Dad, rode a lot of horses, and weeded a lot of gardens. Mom was swept up in Dad’s energy and wanderings, as well as his arms. Theirs was a love of long Idaho country evenings, an Idaho love.

So, there I was the other day at her house putting a threshold strip on the bottom of the west door to help keep the winter wind out when she asked if I had picked up Dad’s ashes. I hadn’t, but I said I would. No problem. The funeral home was on my way home. I’d agreed months ago to pick Dad up and to keep him.

Mom doesn’t want the ashes in her house. She wants me to keep them until she dies. Then she wants her ashes mixed with Dad’s and spread out in the wide-open spaces of Idaho.

On the way to my place, I stopped at the funeral home. The mortician gave me instructions on how to open the box. “It’s tricky. There’s a double lip,” he said. He doesn’t want me fumbling around during some ceremony. Then he said, “The ashes are also in a plastic bag, and most important, they aren’t really ash at all. They’re silica, and they must be strewn more than scattered.”

Silica is not like ash.

I had always imagined that I would toss my parents’ remains on the wind, and they would blow hither and thither. It would be sad but romantic. Their ashes would flutter, mix, and come to rest like an angel down on the landscape. And then they would mix with the soil

and return to every living thing.

When Mom and I discussed where Dad and she hoped that my brother, sister, and I would spread their ashes, Mom said, “Do you remember when your dad and I would go to Roseworth Reservoir to fish?”

“Yes. Jude, the kids, and I went with you a couple times.”

“One night we were the only ones out there. The sky was clear. Coyotes were yipping. We’d caught some fish, and as we sat there having a drink, the stars were so close. As far as you could see, there were no house lights or anything. We were just wrapped in that place. It was calm as if everything was twinkling just for us. Well, that’s where your dad said he wants his ashes strewn. He just said that.”

I know the spot where they sat. I know what Dad wanted and what Mom has agreed to: for just the two of them to be together beneath the yip of coyotes, the rustle of free wind, the lip-lap of shoreline, and a sky that twinkles above mountains and desert—at home in wide-open spaces.

Now as I stare at Dad fettered among my tightly rowed books, I know he’s dreaming of his children spreading his remains with Mom’s glassy silica. And I know there’s not a chance it won’t happen. We children will, on some long Idaho evening, let their love skitter like sand among the sage, and we’ll watch it mingle and come to rest upon an Idaho horizon.