No products in the cart.

Bison in the Basement

Idaho Fossils Get 3D Imaging

By Jennifer Rilke

I didn’t have a pleasant death. I only needed a drink of water. But I was old and tired and just wanted to take the shortest path to the water’s edge. The ground was much softer than I thought it would be, and my bulk sank in quickly. I struggled for a little while, thrashing my head around, but my horns, which I could normally rely on for protection and power, couldn’t save me this time. The suction of the mud was a fatal embrace. I slumped where I was trapped, never to move again.

This is part of the story of an ancient giant bison, a Bison latifrons, that perished more than 72,000 years ago in what is now southeastern Idaho. An all-woman crew of Bureau of Reclamation personnel, headed by archaeologist Nikki Polson and Idaho Museum of Natural History (IMNH) paleontologist Dr. Mary Thompson, excavated the fossil remains of this animal in 2016 from the shores of American Falls Reservoir. The excavation was remarkable in that the bison was more than seventy percent complete and articulated, meaning it retained mostly the same pose in which it died. The soils around the bones indicated that the animal expired in wet conditions, and the position of the body suggested its forelegs had been stuck in the mud, keeping it upright. The mud that trapped the bison also kept predators away, allowing it to decompose undisturbed. Paleontologists believe the animal was an older female because of its worn teeth and the span of its horn cores. After spending all this time with her, we felt we were getting to know the animal, so we named her Jasmine.

I’m an archaeologist and the museum property custodial officer for the Snake River Area Office (SRAO) of the Bureau of Reclamation, which means I oversee the management of an extremely impressive collection of ancient fossil bones from many extinct animals, all of which were collected in Idaho. During the final 130,000 years of the Pleistocene epoch (the last Ice Age that occurred between 2.5 million and 11,700 years ago), four species of ancient bison occupied North America (B. priscus, B. latifrons, B. alaskensis, and B. antiquus). Remarkably, fossils from all four species have been recovered in the larger American Falls Reservoir area, which was a floodplain and lake during Jasmine’s lifetime. Today, our continent can claim only one species of bison—the modern Bison bison, commonly referred to as the buffalo.

In addition to ancient bison fossils, the SRAO collection contains mammoth, giant ground sloth, camel, extinct horse, short-faced bear, dire wolf, saber-tooth cat, and various small mammals, birds, fishes and turtles. The collection resides in the John A. White paleontological repository at IMNH, on the campus of Idaho State University in Pocatello. Of course, I’ve been in the large basement room where the collections are stored many times, and yet walking through that door and seeing the open shelves of fossils is, for me, absolutely thrilling—every single time.

3D prints of cranium of "Junior."

Brandon Jacob 3D-scans the specimen "Humpty Dumpty." Kirsten Strough photo.

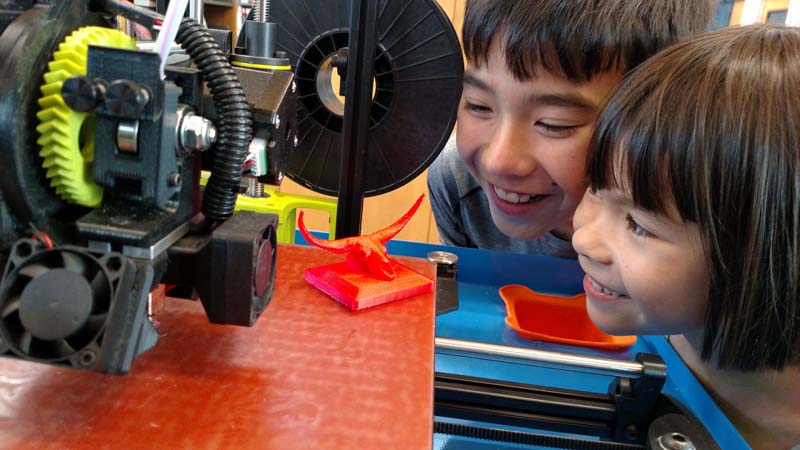

Nium (standing) and Aysha make a 3D print of a bison cranium. Jennifer Huang photo.

The children check out their creation. Jennifer Huang photo.

Humerus bone from an ancient bison. Idaho Museum of Natural History.

The humerus 3D-scanned. Idaho Museum of Natural History.

The specimen "Mary Lou." Idaho Museum of Natural History.

The 3D scan of Mary Lou. Idaho Museum of Natural History.

"Humpty Dumpty" 3D scan. Idaho Museum of Natural History.

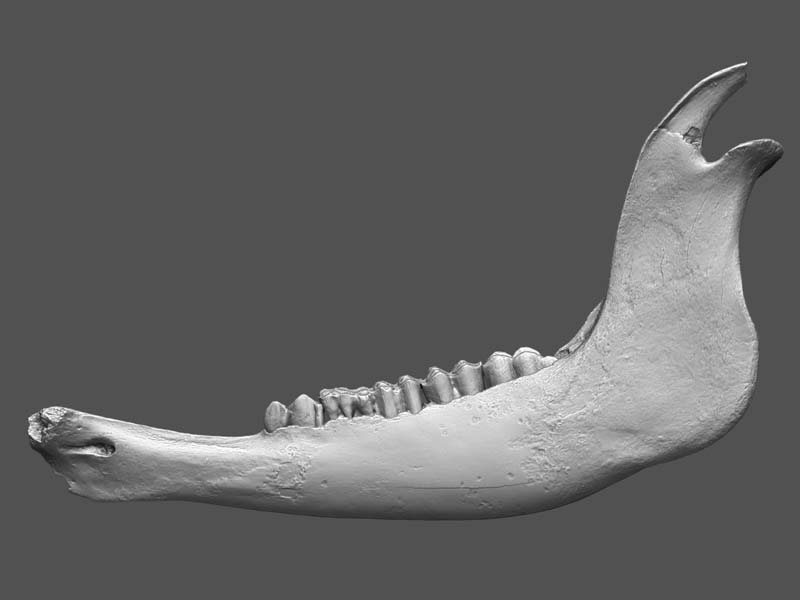

An ancient bison mandible. Idaho Museum of Natural History.

The mandible 3D-scanned. Idaho Museum of Natural History.

Scanning a fossil at the Idaho Virtualization Laboratory. Kirsten Strough photo.

Excavation of "Jasmine." Mary Thompson photo.

A composite "Frankenbison" model from 3D scans. Idaho Museum of Natural History.

As the steward of these specimens, the Bureau of Reclamation is responsible for ensuring that they’re accessible to the public. While some objects spend time on exhibit at museums across the country, the vast majority of these archaeological artifacts, natural history specimens, history objects, ethnographic items, and artworks are kept in storage, where they can be closely monitored and climate-controlled. Fossils, in particular, can be quite fragile and should not be moved around. So, how could we ensure that the public could see them?

We didn’t have to look far to find the answer. The building where the collection resides is also home to a state-of-the-art division of the IMNH called the Idaho Virtualization Lab (IVL). It specializes in three-dimensional (3D) imaging and digital representation of museum objects. In other words, the technicians make exact replicas of real-world objects into computer models. With their equipment and software, these experts can create highly accurate scans of an artifact without physically harming it. The scans can be used to make astonishingly realistic digital 3D renderings that can be turned around with the click of a mouse, almost as if you were holding it in your hands. Fossils can then be studied within a wholly virtual environment. The lab was awarded funding from the Department of the Interior Cultural and Scientific Collections Program through the Interior Museum Program to begin 3D scanning of the most comprehensive assemblage of fossil specimens in its collection—the ancient bison.

Because of its size, B. latifrons may be the most intriguing of the North American bison species (we Americans do seem to share a “bigger is better” attitude). Adult male B. latifrons stood just above eight feet tall at the shoulder, with horn spreads of similar length, and weighed about 4,400 pounds. These animals, which truly put the “mega” in “megafauna,” are nicknamed “giant” and “long-horned” bison. Much is yet to be learned about B. latifrons, including the extent of the difference in size between males and females, diet and socializing, and information about growth and life stages, as well as additional inter-species comparisons—all of which could be gleaned from physical remains. This is where 3D scanning and modeling can really contribute to furthering our understanding of these incredible creatures.

The genetic and evolutionary relationship among ancient bison is not completely understood, but in Australia, specialists in ancient DNA are attempting to piece this together using complete genetic sequence samples (genomes) obtained from the fossils at IMNH. That’s right, these Idaho fossils are attracting the attention of researchers worldwide to help answer long-standing questions about extinct animal migrations and lineages.

The experts at IMNH, who know more about these fossils than anyone else, worked together to select more than 150 specimens for our digitization project. All of the complete and partial skulls and horn cores from the collection (including examples from all four extinct bison species) were chosen for the project. These specimens were selected because cranium attributes and measurements are still considered key to learning the most about the individuals. At least one representative fossil of each sub-cranial (below the head) bone from throughout the rest of the body also was chosen. Assessments, including photographs, were initially performed by museum specialists for each fossil to identify any issues that might need to be addressed about their physical condition before relocating them to the laboratory for scanning. Large fossils, such as the very large skull specimen called “Humpty Dumpty,” that were considered too fragile or awkward to move upstairs safely, were scanned by the team with hand-held portable instruments.

The scanning process, which is non-intrusive, works by shining a laser over the entire surface of the fossil. The computer calculates the time it takes for the laser beam to bounce back to the emitter and the angle at which it bounces. All scanned sections then are connected into a single 3D model. Stationary scanning can happen rather quickly even while maintaining a high level of precision. Using the handheld apparatus is rather like painting light around the object until it has been completely covered. The scanned sections are shown on the computer screen in real time, so the specialist can keep track of where any gaps may be and make sure they get “painted,” too. The raw data can include bits of the table or support on which the fossils were scanned, requiring a cleanup and fine-tuning process that’s more time-consuming and patience-testing than the scans themselves.

Even without coloring the models to create photo-realism, the detail of the 3D-modelled surfaces is remarkable: exactly like the original fossil. IVL experts also create digital bases or stands on which the models can be displayed in virtual reality. When a scale is included in the final scan model, scientists and researchers can perform their studies on the models just as they would with the real fossil specimens. Of course, a big advantage of using the 3D models in these studies is that the actual fossils don’t need to be physically moved, saving them from the potential damage of wear or mishandling.

The lab’s work is currently being used online by the Interior Museum Program in a tribute called, “The American Bison: A National Symbol,” which includes a 2D representation of a composite model of B. latifrons. The composite was created digitally using separate scans of bones within the collection. While Reclamation doesn’t have one hundred percent of any individual fossil bison, we do have all the parts necessary to assemble a whole specimen. The manner of its creation harkens back to the popular Mary Shelley story, and the composite model is lovingly nicknamed “Frankenbison.”

All the IVL bison scans are available online for public viewing and download. If an actual object is needed for study or display, the scan files can be used by anyone, almost anywhere, to create 3D prints. Many public libraries in Idaho have 3D printers that can be used for free with an appointment. I tried this myself, printing a scan file at a public library in Boise, and bringing home pint-sized replicas of one of only a handful of complete B. latifrons crania in the world.

Nikki Polson, who excavated the Jasmine fossil, said, “When people are able to see and manipulate fossils without damage to the collections themselves, they truly become a public resource.” That’s also useful to the public because fossil excavation on federal land is illegal without a permit. In an unguarded moment soon after Nikki’s official blurb, I think she nailed the excitement of all of us involved with this project when she exclaimed, “It’s aww-suumm!”

I had a very pleasant day today. It started like any other, with my fellow fossils resting comfortably in the basement of the museum. We are rarely disturbed here, which is to our liking, but on this day, a few of us became the center of attention. People very carefully brought us each into an open area of the room and slowly shined a red light over every inch of us. It didn’t hurt, or even tickle, but we got the impression that what was happening was extremely important. There was mention of our likenesses being made available to everyone all over the planet, and children, teachers, scientists, and curious people everywhere would be able to see and learn about us—as if they were actually here with us in the basement. We all have stories to tell, each one of us. I’m going to rest again, on my shelf with the others, but I’m also going to be at people’s fingertips, wherever they are, so they can learn my story.

To experience the virtual bison and learn more about the digitization project, visit usbr.gov/pn/snakeriver/landuse/culturalresources/paleo.html and virtual.imnh.isu.edu/BoR

To see the Interior Museum Program’s tribute to the bison, visit google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/exhibit/fwKiwL5VAXuXJw

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only