No products in the cart.

Digging Up the Past

Lewiston Students Uncover Normal Hill Cemetery’s Long-Buried Secret

By Steven Branting

Graveyards are traditionally permanent, inviolate resting places deserving of community care. For various reasons, however, some cemeteries have needed to be exhumed and transferred to new land. In 1888, Lewiston found itself in just such a predicament as the town began to stress its original boundaries along the Snake and Clearwater Rivers, the spring floods of which repeatedly destroyed property and hindered business growth.

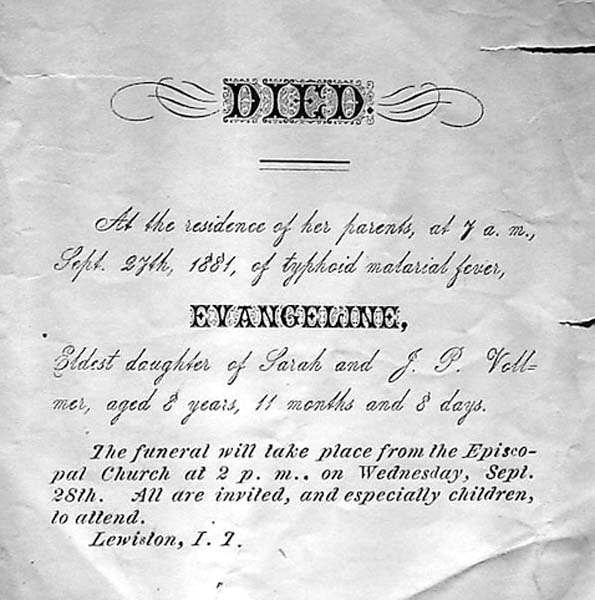

Three unidentified children sit at the grave believed to belong to Evangeline Vollmer. Photo courtesy of Nez Perce County Historical Society.

Students use ground-penatrating radar attempting to locate a long-rumored mass grave. Photo by Shann Branting.

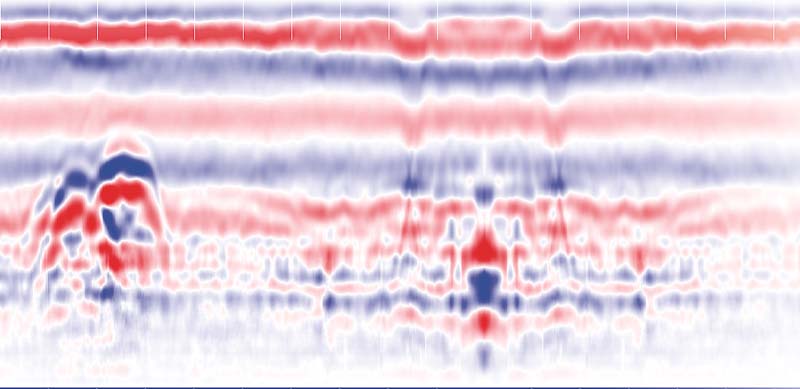

Two graves are revealed in this color profile produced by the ground-penetrating radar.

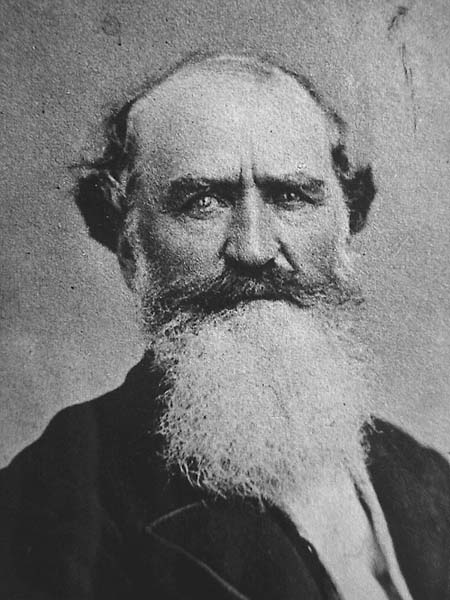

A photo of Evangeline, not long before her death.

The death notice for Evangeline Vollmer.

Famed Oregon Pioneer Robert Newell, who was buried in Lewiston's original cemetery and later moved.

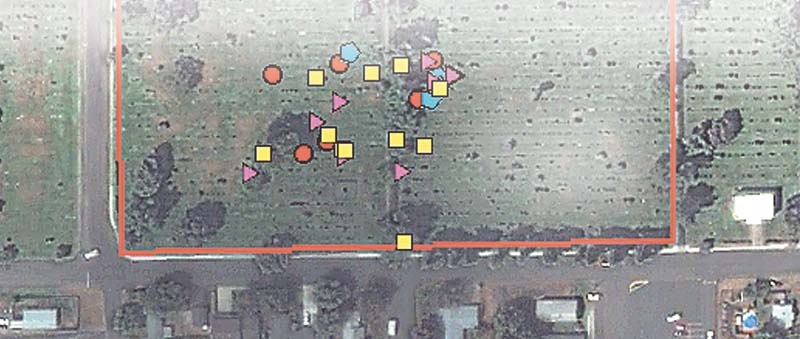

A satellite image of the Normal Hill Cemetery is overlaid with symbols indicating the different dates of death.

Lewiston’s cemetery was the stereotypical “Boot Hill,” a plateau above the town where interments had been performed since the early 1860s. Regrettably, the eight-acre site was increasingly perceived as an impediment to civic “progress,” its proximity to the future neighborhood of the town’s wealthiest families considered undesirable. The cemetery’s disturbing lack of upkeep and state of disrepair aggravated the situation. Cows roamed freely among the graves, trampling wooden and stone markers. The stately, whitewashed fencing installed at great expense in 1879 was now drab, decayed, and falling down. The cemetery had become an eyesore, not what one would expect of an emerging shipping center and the site of the Pacific Northwest’s first telephone service.

After several proposals were debated and discarded by the city fathers, a new forty-acre site was selected in an area deemed to be distant enough from the town’s center to pose few problems for city developers. In December 1888, the city council officially banned any further burials in the old cemetery, and in the spring exhumations began. The platting records were woefully inadequate. Indeed, no map of the original cemetery has ever surfaced. By May 1893, the city council was obligated to “devise ways and take necessary steps” for removing the remaining graves and quickly passed an exhumation ordinance, contracting with Dudley Gilman “for the removal of the dead from the old city cemetery.” His costs were to be passed on to the surviving family members. Since he was related to a popular former mayor, no one openly questioned Gilman when it came time to pay his bill—$752.30 for no more than a few days’ work. Later that year, he was authorized to plow and harrow the grounds, taking the more than seventeen hundred feet of cemetery fencing as payment.

However, apparently the city council was not satisfied that every body had been removed. A brief notation in the city council minutes of the May 6, 1895, proclaimed: “It appearing to the satisfaction of the Council that certain persons were buried upon lands owned by the City…the Marshal was ordered to notify the interested persons to remove such bodies at once to the new Cemetery of the City.” The “interested persons” were none other than long-time residents and influential Jewish businessmen Abraham Binnard and Robert Grostein, who had been resisting the exhumation ordinance for nearly two years. But more about that later.

That same year surveyors divided the old cemetery property into four lots for potential sale, but plans for a new hospital, church, and Masonic Temple came to nothing. By 1900 a major portion of the grounds had been dedicated for use as Lewiston’s first municipal park. In 1905 a new Carnegie Library opened, and the Idaho Supreme Court Library was erected. Trees were planted throughout the park. In 1911 a local women’s group spearheaded the construction of a large fountain—complete with a statue of Sacajawea—in time for a speech by President Howard Taft from the park’s band shell, the only time a sitting president has visited Lewiston. The site of the old cemetery had been transformed, its legacy obscured by the circuitous paths of community development.

Adding to the usual graveyard mystique, a persistent story circulated that a mass grave had been dug in the new cemetery (now known as Normal Hill Cemetery) when the unidentified remains from the old burial lots had been gathered and transferred to the out-of-the-way unmarked site. A current lot map shows most of an entire row with the penciled annotation “NR,” which has long been assumed to mean “no room” or “no record.” It would take a group of dedicated students and some space age technology to unmask a truth more interesting than anyone imagined.

As a consultant for gifted programs, and a cartographer for the Lewis-Clark Rediscovery Project, I decided this forgotten cemetery would be a perfect puzzle for my class of seventh-grade students at Jenifer Junior High School. Using geographic information systems (GIS) with the popular software ArcView, we set out to uncover the truth behind the mass-grave rumor.

In late October 2001, I posed two unique and local GIS questions about the cemetery relocation that needed more reliable answers: First, in what sequence were the old cemetery graves exhumed? Second, in what pattern were the remains re-interred? Bolstered by two months of comprehensive instruction, the students undertook Phase 1 of their project, setting about to create a database of every grave in the Normal Hill Cemetery dated before 1889. After alerting city officials about the project, I divided the students among the stones to search through more than eighteen thousand gravesites. “This proved to be an interesting task with so many headstones to search through,” says class member Nate Ebel. Each identified grave was catalogued and marked as a waypoint with exact latitude and longitude coordinates using the global positioning system (GPS). Eventually, the information from 128 gravesites was stored for the years 1867-1888.

With initial fieldwork completed, Phase 2 afforded the students the opportunity to use their newly mastered software skills. The team uploaded GPS data into ArcView as a file that could be sorted like a common spreadsheet and displayed with distinct symbols for separate sets of dates. When projected over a satellite image of the cemetery, the data solved the second question and provided information that led to a reasonable answer for the first. The students saw that the most ordered pattern of reburials occurred with graves dating from the latest period: 1885 to1888. This finding convinced the research team that the graves in the original cemetery had been exhumed from the newest to the oldest graves.

The gravediggers seem to have started with the remains most easily accessed. The computer images also supported the hypothesis that the later the burial, the more likely the site had a stone marker or could be found from undertaker records. Lewiston did not have a local monument company until 1903. The nearest suppliers were in Spokane and Walla Walla, both a hundred miles away by stagecoach. Wooden markers didn’t weather very well. Many graves just could not be found, and apparently no one went prospecting for them.

Later the students discovered that a separate Masonic section had existed. Burial there seemed to have ensured an early exhumation. The original accounts ledger for Normal Hill Cemetery later revealed the important role played by family wealth and influence in the exhumation process.

Even at this early point, the impact of the students’ project was far-reaching. In the spring of 2002, the team earned the Community Atlas Award for international excellence from ESRI, the world leader in GIS software, and the National Geographic Society. Team members have since spoken at several international, national and regional conferences, and have presented to members of Congress in Washington, DC.

However, the team’s discoveries did nothing to unravel the mystery of the legendary mass grave. GPS units were useless as tools to explain that conundrum. Phase 3 would need to embrace a more advanced approach called remote sensing. I received the support of the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NCRS), a division of the United States Department of Agriculture, and in July 2003, James Doolittle of the NCRS joined students Nate Ebel and Chris Wagner and myself in surveying the entire area where the mass grave was rumored to exist. Using ground-penetrating radar, we beamed low frequency signals through the soil to a depth of about two meters (the proverbial “six feet under”) hoping to reveal anomalies or disturbances in the strata. Several hundred scans were produced and digitally stitched to create three-dimensional color profiles. Everyone was keenly anticipating a set of positive readings.

“After learning how to read the scans, we were surprised to find nothing,” Ebel remembers. The resulting images were conclusive: No vestiges of a mass grave could be found. “This project proved to be a riddle with many interesting twists,” Wagner adds. The old story was merely a tall tale. “NR” was in truth “no remains.”

Will Rogers once observed, “It’s not what we don’t know that gives us trouble. It’s what we know that ain’t so.” Just when the team thought they had the answers, a bumper crop of questions came in. After all the work, Normal Hill Cemetery was not the focus of the historical problem, just the symptom. Originally planned as the terminal stage of the project, Phase 3 raised new issues no one on the team had foreseen. If the mass grave did not exist, what had been done with the unidentifiable remains?

Embarking in a new direction, the team had to ask itself: How many people had been buried in the old cemetery? Who were they? When did they die? Was there any pattern to the identities of the missing graves? Technology wouldn’t be much help with this part of the search. These were questions needing a more traditional historical technique: research.

Efforts were initiated to locate records and photographs of the site and those who had been buried there. To date that search has yielded two panoramic views and three portraits. In a rare cyanotype, three children sit near a gravesite believed to belong to Evangeline Vollmer, daughter of John P. Vollmer, Idaho’s first millionaire.

A thorough review of obituaries, coroners’ inquests, probated wills, and church records eventually supplied the names of more than 230 people who had been buried at the old cemetery site as early as 1862. The burial records of the local Episcopal congregation revealed that there had been three sections to the old cemetery: City, Jewish and Masonic.

At least two independent sources recounted how “they moved more headstones than graves.” A few older gravesites in the new cemetery had been scanned in the first radar survey, and some lacked evidence of a reburial. Why would these bodies have not been exhumed and reburied? The answer may simply be that since few bodies were embalmed in Lewiston before 1890, the city officials reasoned that little would be found when the old graves were opened. Better a cenotaph, they may have thought, than a lot of effort to find just a few bones or possibly nothing at all. How many headstones and human remains were separated from 1889 to 1895 is an open question, but a conservative estimate places the number as high as fifty percent of those buried prior to 1875. What had once seemed mere rumor and idle speculation was now distinctly probable: The city park in Lewiston must contain a large number of unmarked graves.

Why did the Binnards and Grosteins resist an exhumation order and force Lewiston to initiate legal action against them? The reason was basic: their deeply-held faith. Jewish custom allows for exhumations, but only in special circumstances. No rabbi was easily available in the 1890s. The headstones of Birka, Jacob, and James Binnard, as well as two Grosteins (Moses and Earley), can be found in Normal Hill Cemetery, all dating from before 1889. More problematic, however, is whether their remains actually lie under those stones. Are their bodies still where their families originally buried them and wanted them to stay?

This leads us the next proposed phase of the project. In Phase 5, the old cemetery will require a complete ground-penetrating radar survey, aided by the installation of a temporary GPS base station receiver. Handheld units can then triangulate their readings and fix the positions of unmarked gravesites to within a few inches as they are found by radar. The urgency of this survey became apparent in December 2003, when six decaying trees from the first planting were felled in the park. Two of the trees were located well within the perimeter of the “city cemetery” section, where the vast majority of unmarked sites are apt to be found. Today old stumps are mechanically mulched to eighteen inches below the surface and to a diameter of five to six feet. I closely examined the debris at both sites for fear that an unmarked grave could well have been disturbed. While no evidence of human remains was found, the event establishes the cemetery’s endangered status, especially since several other trees are reaching the limits of their expected lifespan and so many gravesites are as yet undiscovered.

The radar survey has now been scheduled for fall of this year, and it may well locate the sites of the original exhumations. Correlating the data for the remaining and former burial shafts will provide the details needed to map the distribution of graves, as well as the spacing and arrangement of rows. As a final step, radar will scan the oldest Binnard and Grostein gravesites in Normal Hill Cemetery.

The team will be left with a unique problem. The reclaiming of human remains will be necessary, but city officials are unlikely to approve the excavation of their premiere city park. And what would be done with more than a hundred sets of remains if they can be found?

Wishing to achieve some degree of historical closure to the project while remaining sensitive to the community, in Phase 6 the team will submit a position paper based on legal precedent, petitioning that at least one gravesite be excavated and studied in forensic detail to learn whatever possible about the person buried there. The recovered remains would then be buried at Normal Hill Cemetery under a marker inscribed “Unknown from Pioneer Park,” symbolically honoring the other individuals still interred at the old burial grounds. As a final gesture, a monument of local stone would be placed at the exhumation site to commemorate the remaining graves in Pioneer Park, bearing the message “Dedicated to the Pioneers of Lewiston Buried Here Unknown but Not Forgotten by Its Children.”

Asking the right question opens the doors to authentic student learning both inside and outside the classroom. Every community has its intriguing historical questions that can be analyzed by inquisitive students who can be empowered with appropriate technologies to unravel local mysteries and enhance the community’s understanding of itself. Who knows, the truth may be more interesting than any fiction. [/private]