No products in the cart.

Steam Days

By Linda J. Henderson

“Oh yes!” he says wistfully, “They have a distinctive sound, and they talk to you. That steam would go into the cylinders and dissipate out through the stack, and that was a sound that you never forget.”

That is how Harlan “Toad” Turner describes running a steam engine when he was a young man working on the legendary Camas Prairie Railroad. Now eighty-four, he still has the frame of a big, strong man. As he reminisces, he waves his brawny hands in the air as though he were still moving the Johnson bar and adjusting the dampers.

The old 1618 engine doing its part as a "helper." Photo courtesy of Harlan L. Turner.

Toad looking very comfortable in the cab of his engine, backing into the rail yard. Photo courtesy of Harlan L. Turner.

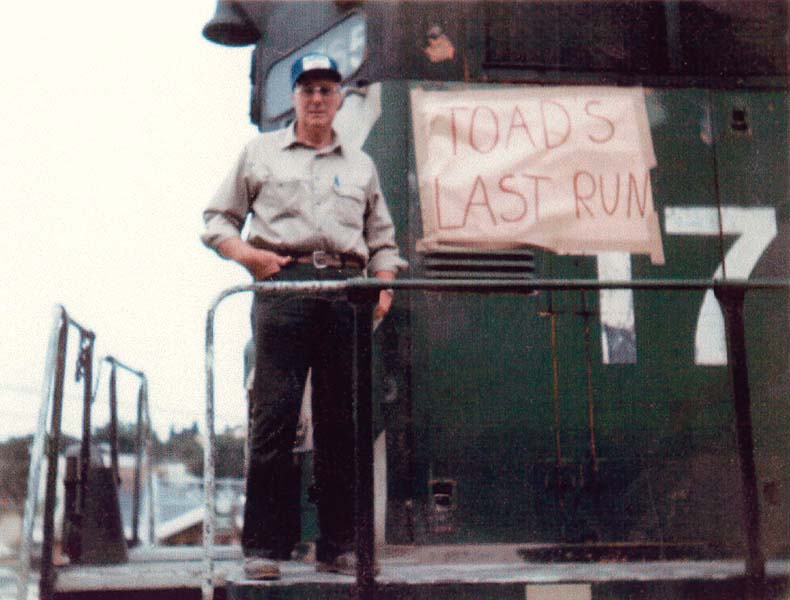

Toad on the back of the "bug" car 1765 at the end of the last passenger run from Grangeville to Lewiston. Photo courtesy of Harlan L. Turner.

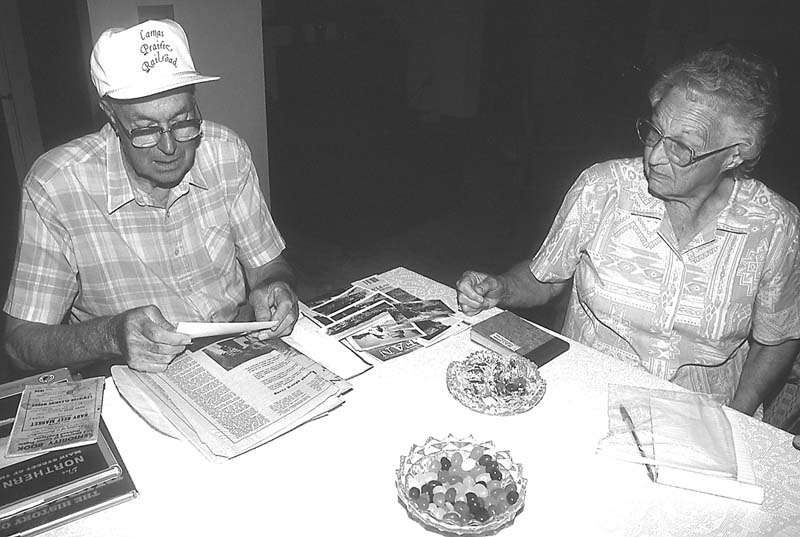

Toad and his wife, Neva, go through old pictures of Toad's "railroadin' days." Photo by Bud Henderson.

Harlan earned his nickname as a youngster. After hopping through a barbed-wire fence with a bunch of his friends, one of them said, “Why, you jumped through that just like an old toad.” The name stuck, he says, and his wife Neva says she has to use the nickname in the phone book or his friends can’t find him.

Now retired, Toad loves to talk about his “railroadin’ days.” He started out in 1944 as a young man shoveling cinders out of the pits at the roundhouse in Lewiston. From there he moved up to clerk in the station at Spokane. A fellow had to wait for an opening in those days, as the ones with seniority got their pick first. Finally there was an opening for a switcher, then for a fireman, and Toad moved up. But he wanted to run those engines.

“I worked my way up,” he says proudly. “When we were firemen, they would let us run the engine in certain spots. But to become an engineer, we had to serve as an apprentice while we studied air and diesel, and all that went along with the promotion, until a vacancy was created.”

Northern Pacific gave the young hopefuls a book to study hydraulics, air, and diesel. The men studied from their book on their own time to prepare for the test. His wife Neva loves to talk about the years that Toad and his friends were studying to become engineers.

“At night I used the book to quiz them to see if they knew the answers.” Neva says. “By the time Toad got his certificate, I felt like I knew as much as he did. I couldn’t have run the engine, but I sure could have passed the written test.”

“They ran Mikados in those days,” Toad says, “but because it was during WWII the company renamed them ‘McCarthers.’

“Oh, I loved how fast the steam engines would go.” he grins. “When you’d get up on the prairie on a straightaway, they could really roll. You had what they call a Johnson bar on the inside, and a throttle—you worked them together—and the farther down you had your Johnson bar, the more powerful it was.

“I used to love to take the Spokane to Paradise, Montana, run, because I could get up a full head of steam and let ’er rip. I can still hear them going up the track.”

But running the Clearwater route on tracks that wind along the river, things were different. This route was primarily used for logging operations. At night they would use a steam engine to bring in empty log cars, and in the morning they would bring the loaded cars out of the forest to the Potlatch Forest Industries lumber mill in Lewiston.

“Why, I remember when they was loggin’ in the Headquarters area, and Orofino was a booming logging town. On the Headquarters run, they were all steam engines, and they were all oil burners. The reason for that is they didn’t want to set any fires in the forests.

“Those mountains are just about skinned out now, but when I first went to work there everything was all cross-cut hand saws used by big Swedes. Big men, boy, they was big! They didn’t have any motor tools then, and those big men would pack their big old crosscut saws over their shoulders like a monkey wrench. And there were places they could store them while they were in town.

“Mrs Helgerson built a big old hotel at the end of town, and I think it’s still the Helgerson hotel, and those loggers would pay her a lot of money for a place to flop down. They’d come into town with their big old hats on, and they’d get a jug and away they’d go to “those houses.” Those guys would get drunk and they’d be going all night. Orofino used to be a wild town.

“Now we railroad men stayed at Jenson’s place. That was the mortuary. And I slept in the slab room. Oh, it was a beautiful time!”

But the legendary Grangeville route of the Camas Prairie Railroad was the most famous, “the railroad built on stilts,” they called it. The line followed the crooked Lapwai Canyon to the base of Winchester Grade, then up to the prairie. To ascend the rugged mountainside, the train climbed a constant three-percent grade, through seven tunnels totaling 3,003 feet, and over seventeen wooden trestles, varying in length from 50 to 685 feet.

The most amazing of the trestles used then was the “Halfmoon Bridge,” a dramatic structure containing nearly one million feet of lumber. It was 685 feet long, 141 feet high, and was built on a fourteen-degree reverse-curve.

The “Horseshoe Tunnel” was so long and curved that you couldn’t see daylight from the middle. A steam engine, belching smoke, cinders, and steam filled the air quickly with ashes and smoke, making it difficult for the men to breathe. The crew solved the problem by taking off a glove and breathing into it until they pulled out into fresh air again.

“Steam engines was awful dirty!” says Toad. “I’d wear bib overalls, and a jumper, and a shirt with a bandana around my neck to keep the cinders from coming down and workin’ on ya.’ Poor Neva used to scrub my overalls on a rub board until her hands were sore, ’cause a washing machine wouldn’t do the job.”

One section of the Grangeville route was an engineer’s greatest challenge. Not just anybody could run it. Climbing the twelve-mile incline frequently required two engines working together to get a loaded train to the top. Slipping wheels were the biggest problem on the grade, which would bring the upward progress to a halt. “Then the engineer would lock the air brakes,” Toad says, “and rest the load back against the brakes, taking advantage of the springs in the couplers. Then, by adjusting the steam, and pulling down on the Johnson bar, you could engage the drive wheels and lurch forward right when the pressure was released from the couplers.”

By pulling another lever, Toad released sand on the tracks to improve traction. The combination of these efforts would get the train moving slowly upward again toward the prairie at the top of the three thousand foot climb. Once the line got to the top of the grade, it was straight going again on a wide expanse of rolling prairie to Grangeville, crossing no less than forty-five additional trestles.

On the way down, the challenge was to keep the train going slowly enough to keep the brakes from getting too hot and to avert a runaway. “Even at fifteen miles an hour,” Toad said, “you could feel that old Half Moon bridge sway out about five to eight feet. And with the shaking the engine would give it, you could look down and see the timbers just a poppin’ out as you went across. But the trestles never fell, and the boys would just go back and repair them.”

In those days there was passenger service, too, from Lewiston to Grangeville and back. At first they had their own passenger trains, then the railroad tried mixed trains with both passengers and freight. That didn’t work very well, so finally, in an attempt to cut costs on passenger service, the Camas Prairie Railroad started using B-12 and B-14 gas/electric cars. Toad ran those, too. He was always recruited to make the run when the snow was particularly bad up on the prairie.

“My boss would tell me to go out there and bring that car down safe, and, by golly, I’d do it. Sometimes I’d have to bust through the snow banks to get through. So I would put a string on the throttle and jump over the motor towards the back so that if the front caved in I wouldn’t be trapped up there. I came back once with the shutters all bent, and lights on the side were off, but I made her through.”

Folks called these hybrid trains “bugs,” and in addition to passengers, they were used to carry mail, groceries, and small parcels. Eventually passenger service became unprofitable and that service was stopped. Toad ran the last bug car to Grangeville and back to Lewiston in the early 1950s. The boys threw a little party for him at the yard. They knew a lot of change was in the wind.

The legendary Camas Prairie Railroad has had a long succession of owners. It was built at the turn of the century by Northern Pacific and Union Pacific, and later was owned by Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe. It was finally sold to Camas Railnet in 1998.

Toad has seen a lot of changes since he began working for the railroad in the 1940s. All of the steam engines have long since been replaced with diesels, and loads of logs have been replaced by hoppers full of wheat and other grains. Now even that is changing. More and more farmers are using trucks with huge trailers instead of trains to get their grain to the elevators.

Diminishing business and the cost of repairs finally caught up with Camas Railnet, and they petitioned the transportation board to abandon the aging tracks and trestles. Nearly one hundred years-old, the trestles were in a shambles, and the rails needed major repairs.

“I don’t see how they could continue using that track,” Toad says in his living room. “The costs of rebuilding those trestles in these days would just be too much.”

Toad is right. Camas Railnet has abandoned the tracks that he knew so well. One by one, tracks into the timber forests, and most recently, the treacherous climb up Lapwai canyon, are being disassembled.

Oh, but you can’t take away those memories from Toad. Sit with him for a while and listen to his stories, and pretty soon you can feel the cinders a’crawlin’ down your neck, smell the firebox and hot oil, and hear that once-familiar sound of steam being released from huge cylinders, as he lives those days again.