No products in the cart.

Gone Primitive

A Deep-Woods Childhood

By Marco Horsewood with F.A. Loomis

One evening in Los Angeles, Walter Weymouth took my mother for a walk and asked her, “If you could lie on your back in the grass and look at the stars in the heavens and make a wish that could fulfill a dream you had dreamed more than once, what would it be?”

I think that question implied she was valued in a way she had never experienced. Their courtship lasted almost two years, and my mother, Maria Assenccion Martinez De, came to trust him completely.

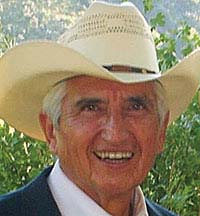

Maybe she was looking at his heart more than his outward appearance. He had a bald head and a round face upon which his wire-rim glasses rested far forward on the bulb of his nose, making his gray, overgrown eyebrows seem larger than his wise, dark-green eyes. He was six-foot-four and at fifty-six, was nearly twenty-five years my mother’s senior. He wore starched white shirts uncomfortably. The top shirt button was never fastened and his tie was always loose. He wore dark blue, double-breasted business suits, but they were never pressed and his suit coat always hung lazily over the back of his chair. The only thing that suggested his job as an attorney for the downtrodden of East Los Angeles was his five-button vest, which he wore buttoned up over a large barrel chest. Always tucked inside his trousers, not well hidden under the vest, was a .38 revolver.

Walter was an outdoorsman and he would escape at least twice a year to some primitive place where he could hunt and fish for several weeks. After returning from a hunting trip to Idaho, he excitedly told my mother, “I have worked all my life doing things for others and never for myself or the ones I love. I think I have a chance to escape and to change all that. There is a place in Idaho that is so secluded and so close to the end of the world that you can at least see the end of the world from there. I want to go and not look once over my shoulder at what I left.”

It was 1946, and I was nearly three years of age. With Walter’s help, my mother had been allowed to remain in the United States on a temporary visa. My mother, young and beautiful, proposed marriage to Walter and he accepted. She would now have the opportunity to get citizenship but more important, he planned to adopt me. My biological father, who worked high altitude beam construction on Los Angeles skyscrapers, disappeared into the crowd of the city several years before my mother met Walter. She never married my father, whom we believed was Mohawk or Nez Perce. I am not clear about all the reasons why Walter did not immediately marry my mother, and I am not sure why I did not become his son in name. She hinted it had to do with expediencies surrounding their purchase of the Big Creek Lodge.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only