No products in the cart.

Mary Jane’s Farm

Growing Organically and Cultivating Fame in Rural Moscow (Idaho, Of Course)

By Carol Price Spurling

Nestled at the base of Paradise Ridge, in the rolling Palouse hills eight miles south of Moscow, lies a small organic farm, a place owned by a woman whose name is becoming very big: Mary Jane Butters. In the fall of 2003, Butters received a $1.3 million advance for her book, Mary Jane’s Ideabook, Cookbook, Lifebook: for the farm girl in all of us. The book, the first installment of a two-book deal,was released in May. Now that her publisher,Random House, is sending her on a national book tour this summer and dropping big bucks on full-page ads in the New York Times, fame is becoming a mixed blessing for Butters. She no longer jumps when journalists call. Nor when show business calls. She was recently offered a television series. She declined.

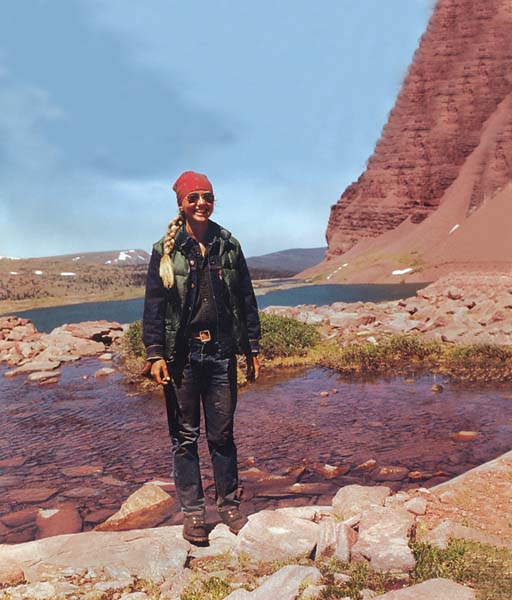

But she won’t mind if you call her Mary Jane. Formalities just don’t fit this petite woman, dressed for the day in a white thermal shirt and black down coat and jeans, and a red bandanna knotted around her neck.Her long blond hair, going silver around her face, is pulled back into a long braid. Shiny-costume aquamarine earrings give her hands something to fiddle with while she talks.

Not Your Typical Farmer or Celebrity

She’s a farmer, carpenter, entrepreneur, magazine publisher, photographer, and writer hitting her stride now, at age fifty-one, after an early career in the U.S. Forest Service. In the early 1970s, Mary Jane moved from Utah, her childhood home, to spend two summers in a northern Idaho fire lookout tower near Weippe.Then she spent two years at the Moose Creek Ranger Station in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness,working as the first female station guard in the Selway with its legendary fire control officer,Emil Keck.

After ending her Forest Service career, and with the idea of having a family beginning to stir, Mary Jane moved with her husband to a ranch on the Snake River. And it was at that ranch, working as a farmhand, that she seized and held onto the dream of living on her own farm. She and her husband finally found her dream property in Latah County, and they moved there with their children, young Meg and baby Emil, in 1983.Mary Jane was twenty-nine years old.

“My place showed up one day as an ad: ‘Remote old homestead, five acres, orchard,well, $45,000.’ It had been rented to some Hell’s Angels and they’d spent a year throwing their garbage and beer cans out the back door,” Mary Jane recalls.

Mary Jane forged a strong relationship on the site, but it turned out to be with the land and her children.Her marriage fell apart after a year. Two decades later, she laughs about the lot she had to deal with: a drafty old farmhouse with wood heat, an outhouse, and a baby in cloth diapers.

“My Forest Service experience prepared me for that life,” Mary Jane recalls. “I knew how to split firewood. So you have to go to the bathroom in a bucket? That’s OK. So you can’t wash your clothes every day? That was OK too.”

She insists, though, that she wasn’t a hippie, despite appearances.“I breastfed my kids, but it was on a schedule,” Mary Jane says.

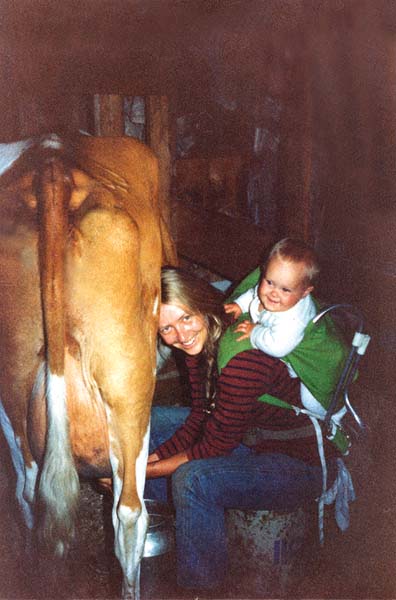

She paid the bills by working as a seamstress and an upholsterer, occupations that allowed her to work with her children nearby. Her worktable rested on sawhorses and the kids played “fort” underneath.A photograph from those early years in Idaho shows her milking a cow, wearing daughter Meg in a backpack, and smiling.

Idaho organic farmer and magazine publisher Mary Jane Butters. Bruce Andre photo.

With daughter Meg on her back, Mary Jane milks a cow, circa 1980. Photo courtesy Mary Jane Butters.

Mary Jane during her U.S.Forest Service in the 1970s. Photo courtesy Mary Jane Butters.

Morning view of the bed and breakfast at the organic farm in

rural Moscow. Photo courtesy Mary Jane Butters.

Garlic plants on Mary Jane’s Farm in the Palouse hills. Photo courtesy Mary Jane Butters.

Mary Jane Butters with her 1981 biodiesel-powered Mercedes. Bruce Andre photo.

Not Your Typical Farm

After visiting Mary Jane’s five-acre farm, it’s easy to see why a person would want to hang on to it, running water or no. A twenty-minute drive from Moscow to the acreage is picturesque. Rolling past classic Craftsman farmhouses and a grassy trailer park, the road gently climbs out of fields into the pines, winding to the top of the ridge, where it presents you with a sudden, expansive view of the classic dune-like wheat fields of the Palouse stretching south toward the Snake River.

Glimpses of a brand new 10,000-square-foot, three-story “farmhouse” as you approach offers evidence that life has become more comfortable at the farm in the past few years. A sign at the bottom of the iris-lined lane – “Mary Jane’s Farm: Living like we’ll die tomorrow, farming like we’ll live forever” – offers a philosophical welcome.

On this bright early spring day, a biting wind makes it more pleasant to be indoors, where most of the farm’s employees are staying busy. In the basement of the new building, two employees are handling orders and bookkeeping. Nearby, in a spotless and spicy-smelling work area, a crew of three is mixing up a batch of one of Mary Jane’s organic convenience food mixes, sold by mail-order through her catalog, through outdoor stores like REI and Patagonia, and at health food stores nationwide.

Mary Jane originated the idea of selling packaged instant organic falafel, what her kids called “Mom’s Awful Falafel” in its experimental stage, as a way to help some farmer acquaintances find a market for their organic garbanzo beans.The line now includes a wide variety of “office cuisine” and “backcountry cuisine” items such as corn salsa, no-cook curry rolls, African pea soup, and Nick’s couch potatoes (Nick Ogle is her husband, the farmer next door, whom she married in 1993). Mary Jane has also revamped the comfort food of her Mormon childhood, offering an organic all-purpose baking mix, and an organic alternative to the trademarked Jell-O, called the ChillOver.

Finding sources of organic lentils, potatoes, and garbanzo beans has turned out to be more of a challenge than Mary Jane imagined.Her own attempts to raise the raw products didn’t turn out well.

“The hang-up is in the processing.You just can’t find anyone to process a measly two thousand pounds of garbanzos at a reasonable cost when they’re used to volumes closer to six million pounds,” she explains.“In order to process organic anything, they have to clean out the line–that takes a day–and then run mine. I’ve talked a few processors into it, but after it was all said and done, they vowed they’d never do it again.” But the heirloom garlic and some of the herbs used to flavor the mixes are grown right on the farm, and she has found a regional source for organic flour, pasta and cheese.

In the early 1990s,Mary Jane received what she considered to be a strong reaction from Idaho legislators and the powerful Idaho Farm Bureau Federation lobby [the Farm Bureau is Idaho’s largest agriculture lobby group] after she applied with the state’s agriculture department for the right to put “organic” on her packages of falafel. “This Farm Bureau guy growled at me,‘You’re just trying to put ‘organic’ on the label and charge more for it, and we’re not going to let you do it because your food isn’t any different than ours,’ and they sure didn’t,”Mary Jane recalls. Even so, she still speaks highly of her dealings with the Idaho Department of Agriculture.

“Although bureaucracy is always difficult, I was able to find individual employees, who, once they understood what we were about, were willing to help us,”Mary Jane says. “And Idaho is much more open, much less regulated,when it comes to new things like agri-tourism or alternative agriculture. Idaho is a can-do kind of place.”

Things really have changed: the farm got a grant from the bio-diesel; now Mary Jane’s 1981 Mercedes runs on homegrown fuel. (The Mercedes, by the way, was recently painted coral pink, to match one of Mary Jane’s favorite nail polish colors.) In March, Mary Jane was a featured speaker on the topic of “The New Face of Agriculture on the Palouse” for a Moscow Chamber of Commerce agribusiness forum. And in 2001 she received the Idaho Progressive Businessperson of the Year Award.

In another outbuilding, several more employees laugh and chat as they share a pizza for lunch. The main room here is stocked with vintage-looking (Mary Jane defines “vintage” as anything pre-dating the 1950s) aprons, pillows, purses, samplers, and other items made by rural women locally and throughout the U.S., available through her website and catalog. Down a gravel path, just next to the barn, stands a former wreck of a shed, restored on the outside with corrugated steel, transformed on the inside into a gleaming stainless steel but still country-style kitchen, used for staff meals, recipe development, family gatherings, and photos.

In yet another building,more employees are working, keeping company with enamelware dishes and wire baskets and other antiques lining the rafters: props for photo shoots, and inspiration for the design team that creates the combination magazine and catalog–and manages the very large website. One of the more popular features on the website is the “Farmgirl Connection,” a bulletin board where rural women from all over the country (or wannabes) share everything from crochet patterns, to questions about how to raise goats. It’s just one of the ways Mary Jane is attempting to re-create the close-knit support system she grew up with as a Mormon in Ogden,Utah. These days she does without any theological labels.

“The buzzword these days to describe what I had is ‘community,’”Mary Jane writes in her book. “My parents had family, neighbors, and church members . . . I have my family, but for daily neighboring, I have farmhands and employees whom I love dearly. For church, I have shareholders.”

Not Your Typical Entrepreneur

On this April day, Mary Jane and her staff admire the glossy proofs from the new four hundred- page book they’ve just finished–the book that would be published by Random House in May.The advance money she received for the book last fall helped build the imposing new “FarmHouse,” still awaiting plumbing, wiring, and finish work. When it’s done, it will consolidate all the various farm workspaces under one roof, and include a small bed and breakfast as well as Mary Jane’s living quarters. Having just spent six months writing her book, often getting only three or four hours sleep a night,Mary Jane’s in no hurry to get the building done. “My most recent brush with almost going under was after 9-11 [2001],”Mary Jane says.“Just before that happened, my monthly sales of my backpacking line hit $35,000 a month. One year after 9-11, they had slowly dwindled to $1,800 a month.The first thing people do in a recession is cut back on their food budget. I had to lay off employees, I thought my time was up, everything finished. My banker was talking about a farm auction. So I won’t be taking out a bank loan to finish the FarmHouse project. I just don’t want to be in that position again.”

Mary Jane is no stranger to asking for money, but she’s careful about to whom she appeals for help. Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard helped her out with a loan when she was starting out, but Mary Jane talks about the dozens of friends who came to her aid in the lean times.“Since 1993, sixty-five people, our shareholders, have breathed life into my farm by writing out checks that total well over a million dollars,”Mary Jane says in her book.

Now that the immediate threat of going under has passed, shareholders are receiving dividends in the form of fresh vegetables, free-range eggs, and overnight stays in the farm’s wall tents,which are available for paying guests at more than $100 per night. “Our shareholders are glad to see their extra money doing something good,” Mary Jane says.

She encourages others to try her method of raising funds, if they’re willing to do the substantial homework required.The State of Idaho, she says, provided her with brochures and instructions.“Not only that, but they encouraged me and truly wanted me to succeed.”

“We support what Mary Jane is doing,” says Pullman,Washington resident and shareholder Richard Old,who was profiled in Mary Jane’s magazine in 2002. “She’s working to find a way for local farmers to really practice sustainable agriculture here. Helping her achieve that goal will help protect the Palouse I love so much.”

Mary Jane herself doesn’t have a savings account or 401K, preferring to keep money flowing, working as a catalyst for social change. She has a dream that rural women, who are buying land in higher numbers than ever before, can transform the rural economy, maybe even save the family farm. Part of the strategy, and why she’s invested so much energy into her own Mary Jane brand, is what she calls “putting a face to food.” She hopes that someday people will value food enough to pay farmers for its true costs. She wants to see lots of farmers, and especially women, do the same things she’s done, and more.

“Women have the imaginations to see how things can be done differently, and they are less afraid of change, of trying something new,”Mary Jane says. “Grow the ingredients for salsa to sell at the farmers’ market, give salsa-making workshops, and then toss in salsa dance lessons. That’s the kind of thing we have to do to make it work.”

A New, Old Kind of School

Mary Jane has set up a kind of farmer apprentice program for those who’d like some hands-on experience before taking the farming plunge: the Pay Dirt Farm School. The curriculum, and length of the program, is individualized for each student. “I find out about a student’s land, what they want to accomplish, whether they like the harvest or planting side of things, or if they want to turn it back into prairie . . . and we work out a program for their time here at the farm,” Mary Jane says.

Moscow farmer Patrick Vaughan, formerly in the Army for twenty years, says of his Pay Dirt experience: “As I have a family, I was given the flexibility to come out to the farm one or two days a week, ready to work. A mid-day meal prepared by all on the farm crew provided an opportunity to discuss the work we were performing and to ask questions. I was given a comprehensive book on organic farming and was required to read it and take notes on each chapter. I got to witness and participate in the seasonal progression on the farm, from the first conceptual layout of row crops and seed-ordering while there was still snow on the ground, to the dusty, sweaty harvest season. I learned that I do love the work, and I know this because I did it, not just studied about it.”

Happy to Be Here

Mary Jane looks forward to her daughter, Meg, and son-in-law Luke moving back to the farm this summer. They will work on the product development side of the business.

“I’m getting calls from people wondering if they can put ‘Mary Jane’ on their doll or their silverware divider, and I ask, ‘Where’s it made?’ and they’ll say, ‘China,’ and I just won’t do it,” Mary Jane says. “I want to keep people around here employed.”

She’s happy, too, to have her son Emil, formerly an auto mechanic, working on the farm. With her husband Nick’s 650 acres right next door, making the transition to organic, and her adult children nesting nearby, Mary Jane is hopeful about her small farm’s future.

“Meg gets to come with me on the book tour, and then we’ll come home, and I don’t care if I ever leave again,” Mary Jane says. “I moved to Idaho because it had a lot of wilderness, a lot of open spaces, and good land, and it still does. The rural dream is alive here. It can still be done.”

2 Responses to Mary Jane’s Farm

Angela Painter -

at

Do you still have your magazine? I ran across a letter at my moms. It was from your company offering the Little Book of Favorite Farmgirl Secrets and a free issue. Is this still available?

Roy -

at

Enjoyed your article on Mary Jane Farms, is it still a working farm? I would very much like to stop on by and see it and bring along my 5 yr old granddaughter. It’s a little late in the year maybe in the spring. I haven’t been in Moscow for at least 10 yrs.