No products in the cart.

Ripples in Time

A Bridge and a Murder at Race Creek

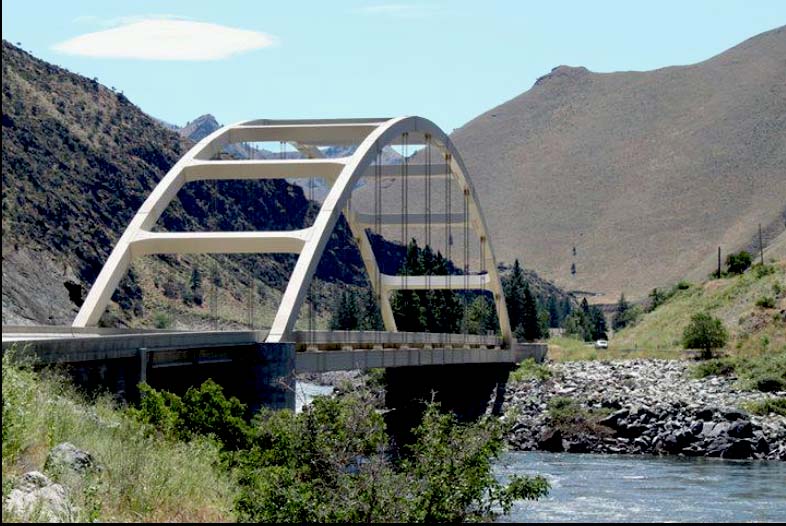

Photos posted on IDAHO magazine’s Facebook page often spark praise and reminiscence among our avid followers, but an image that appeared last fall did more than that: it unearthed the history and lore surrounding one of the state’s most iconic bridges, which included a startling Old West murder story. The photo, taken by Joseph Zahnle, a contributor to both the magazine and our Facebook page, was accompanied by this caption: “The Time Zone Bridge, on Highway 95 north of Riggins on the Salmon River, is where you change time zones between Pacific and Mountain.”

Reader Thad Jiles joked, “I like to fish on the south side of the bridge. About dark, I run over to the north side of the bridge and get in another hour of fishing before it gets dark.”

“Skipped over the time line many times,” Dannette Reker Genasci commented. When our page moderator, IDAHO magazine publisher Kitty Fleischman, asked Dannette if she got jet lag, the reply was, “Yup, I felt a bit of time warp on the bridge.”

“And a great way to ring in the New Year twice,” put in Sharon Knoll. “Been there, done that.”

Heidi Yonker contributed a practical note. “You should know there is a gray area of time zone,” she wrote. “Mountain Time basically extends more than fifteen miles north of the bridge. By the time you reach Slate Creek, Pacific Time is used.”

“Remember the old bridge with all the dents in that cross girder that was a little low for some commercial vehicles?” asked Jon Thorpe.

Kitty had read about that, but hadn’t seen any photos of the old bridge. Reader Ken Stafford said he’d have a look.

Another reader, Dan Wash, pointed out that many folks don’t realize “Time Zone” is a nickname. The official name is Goff Bridge. This sparked Jim to post a link to an article written by Megan Sausser for The Transporter, an Idaho Department of Transportation publication, which described the Goff Bridge as the only tied-arch bridge in the state until the Shoup Bridge over the Salmon River south of Salmon was built in 2017.

Megan wrote that more important than the Goff Bridge’s design was the challenge of putting it in place. The original structure, built in 1935, served two thousand vehicles daily. Its replacement had to be tall enough to stay above high water, strong enough to withstand snow slides, and wide enough for two trucks crossing at once. The problem was that no alternate route existed to cross the river, which meant the original 1.24-million-pound steel bridge had to be moved sixty-five feet west to serve as a detour during construction of its replacement. Scheduled to take seventy-two hours, the move was completed in just thirty-six hours, during which traffic on US-95 was closed through Riggins.

The bridge is affectionately nicknamed the Time Zone Bridge. Nan Palmero photo.

This image sparked the online conversation that led to this story. Joseph Zahnle photo.

The old Goff Bridge in 1999. Richard Doody, Bridgehunter.com

A view of the bridge nowadays. CIFraser, Flickr.

When it was done, project engineer Dave Kuisti was quoted by a Spokane newspaper as saying he felt “pretty confident” the repositioned structure wouldn’t collapse into the river.

Robert Gordon, the lead inspector, expressed relief that the move was finished. “If anything went wrong, the state was basically cut in two and would require a five-hundred-mile detour to get from southern Idaho to northern Idaho.”

“There was even an even earlier bridge,” Jon Thorpe added to the thread.

Kitty provided a link to an article in The Yellow Pine Times compiled by Dianne Dickinson, who had consulted numerous sources. It said before the wagon road from White Bird to Meadows (now New Meadows) was completed in 1903, entrepreneur J.J. Goff offered ferry service across the Salmon River at Race Creek and built a one-mile trail from Race Creek to Gouge-Eye Flat. The area at the mouth of Race Creek became known as “Goff,” and he bought the property, which included a stone house and race or water ditch, used for irrigation and nearby placer mining. In 1894, John Levander purchased it, set up a post office and stage stop, and built a hotel and store he named after Goff. Levander’s sons operated the nearby ferry.

Dianne reported that the first automobile bridge spanning the Salmon River at Goff was built from 1911-12 for the then-huge sum of fifteen thousand dollars. With the bridge’s construction, the first road for vehicles traveling between northern and southern Idaho was completed. Its replacement was built in 1934 and lasted until the current bridge was erected in 1999.

Dianne found and reprinted a description that first appeared in the Grangeville Standard in 1904, which called Goff “one of the most picturesque places along the Salmon River,” and attributed its beauty to the enterprise of Levander. “It is a real treat to the eye of the stranger who is making his first trip up the Salmon River,” the reporter wrote. “He is told that it is a short distance to Goff. He looks up the river and sees nothing but barren hills for miles. He is usually joked and no explanation given. He is just reconciling himself to a long wait and commenting in his own mind upon the estimate of defiance made by his fellow travelers, when he suddenly comes to the little cove in the hillside which he would have never guessed was there.”

Dianne discovered that Levander was born in Sweden, came to the U.S. as a teenager, and worked as a freighter in Boise before he began raising stock. She found a report in the Meadows Eagle of March 5, 1914 that said:

News of the death of John O. Levander reached town yesterday and brought with it sorrow to the many friends of the old pioneer. He passed away Wednesday, February 24, 1914 at his home near Goff, attended by his son and daughter, who have been his faithful attendants during the weeks of his last illness. We understand his funeral will take place tomorrow on the arrival of his children living in Washington County and in Oregon.

Mr. Levander has been a prominent figure in the life of this part of Idaho for nearly fifty years. He was a broadminded man of generous impulses and never forgot the hospitable ways of the pioneer. The stranger, though in rags, never failed to find food and shelter and help at his home. He endured the hardships of the pioneer bravely and enjoyed quietly and without ostentation the prosperity that came to him as a reward of his industry. He filled the honor of many posts of duty and as husband, father, brother, friend and public official proved himself every inch a man. Who can do more?

Dianne’s digging uncovered another story about Goff as the setting of a spectacularly vengeful murder in October 1904. The victim was an apparently peaceable Pollock resident named Tennyson Wright, who was shot over a land dispute. The land office had granted Tennyson a claim to a valuable piece of property, but a stockman named A.E. (Fred) White argued that Wright had taken the land from him by force. Fred struck Tennyson on the head and about the face with his six-shooter, knocking him down, and then chased him about thirty yards before turning back to look for the barrel of his revolver, which had broken over Tennyson’s head. Later, when Tennyson and his wife went to the store in Pollock, they heard that Fred and friends were drinking at a nearby saloon. One of the men entered the store and bought a box of cartridges, which frightened Tennyson into riding sixty miles in ten hours to Grangeville, where he filed a complaint for Fred’s arrest.

On February 24, 1905, the Idaho Daily Statesman reported that Tennyson Wright had been shot dead at Goff by Fred White, who then committed suicide.

Two days later, another story in the Statesman gave a thorough account of the double tragedy, saying the two were on their way to Grangeville, where Fred was to be tried for the earlier assault on Tennyson.

Wright was shot down in cold blood without the slightest warning. The shooting occurred at Levander’s place in Goff and two of the Levander boys were eyewitnesses. Wright was in the act of leaving the house in order to avoid a possible clash with White when the latter suddenly drew an automatic revolver and shot Wright twice, killing him instantly.

The story of the tragedy from its inception to its climax reads like that of a Kentucky mountain feud, excepting that Wright at all times was a law-abiding citizen and did his utmost to keep out of trouble. He was shot at time and again, his horses, cattle, hogs and dogs were killed, his hay burned, his fences demolished, his crops destroyed, and he was even arrested on a trumped up charge of insanity.

The trouble arose over the possession of a tract of land in the Squaw Creek District. Wright being the oldest settler, had first claim to the land. When the survey was made it was found that White’s house and a portion of his improvements were located on the tract claimed by Wright. White contested Wright’s claim and was beaten in the courts.

Last autumn when Wright’s title to the land was cleared by the courts, he notified White that the latter must move his improvements from the land within thirty days. White became enraged and beat Wright over the head with a revolver and threatened to kill him. White was arrested on a charge of assault with intent to kill and bound over to the district court. The two men were on their way to Grangeville to attend the trial when the tragedy occurred.

Subsequent and prior to the last assault Wright’s life was in constant jeopardy. White and his friends were determined to run Wright out of the country and they resorted to despicable and criminal means to accomplish their purpose.

His cattle were shot down, one by one, until he only had one head left. The same thing happened to his horses. Even his dog did not escape the bullets of his belligerent neighbor, and his hogs were killed or stolen. On several occasions White and his friends tore down Wright’s fences and turned their stock into his fields, daring him to interfere. Shots were fired into Wright’s house time and again and when he attempted to save his hay from from destruction by fire, bullets whizzed by his ears.

Through the instrumentality of White and his friends, Wright was arrested on a charge of insanity. Mrs. Wright was away from home at the time and it is supposed that the White faction intended to burn down Wright’s house and barns when the latter was under arrest. The timely arrival of Mrs. Wright on the night of her husband’s arrest, it is believed, prevented the execution of the plan. The charge of insanity was disproven with ridiculous ease and Wright returned to again become a target for his neighbor’s bullets.

Wright arrived at Levander’s on the afternoon of February 22, intending to remain there over night. He was on his way to Grangeville to appear in court. A short time after his arrival White rode up to the house, tied his horse and went into the room where Wright and the two Levander boys were sitting.

What transpired afterwards is told by stage driver Freeman and a Mr. Thompson, who was a passenger on the Meadows stage.

When White came in, Wright said: “I’m afraid of you, White, and I don’t want to go out with you.”

“That will be all right, Tenny,” responded one of the Levanders. “We will not put you in the same room and if you don’t want to you need not sleep in the same house.”

Wright immediately started to leave the room and as he did so White whipped out a revolver and shot him twice. One shot took effect in the neck and the other in the short ribs. Wright dropped to the floor dead.

Immediately after firing the last shot, White dashed out to his horse, mounted, and started back towards his home. The Levander boys started after him on horseback. As they neared Squaw Creek, about three miles south of Goff, they overtook White. As they did so they heard a shot and supposing that White had fired at them they turned back for help. Returning with a posse, they found White’s body about sixty feet from the road, with a bullet through the brain. It is supposed that White feared he was about to be captured and committed suicide.

—The Editors

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only