No products in the cart.

Standing Up to Hate

How a Vandalized Memorial Brought Idahoans Together

By Dan Prinzing

In 2017, I was taken aback when a national reporter covering an attack on the Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial asked if that act of hate represented who and what it means to live in Boise. The memorial had been vandalized with racist and antisemitic language etched into its stone. As executive director of the Wassmuth Center for Human Rights, the builder and home of the memorial, I knew our group had to both ask and answer that question. Yet it seemed to me that the best answer actually would lie in the community’s reaction. How would we respond when confronted by hate? It wasn’t a rhetorical question.

To help answer it, our group began by recalling our own organizational history—and the shoulders upon which we now stand.

The center was named for Bill Wassmuth. In the 1980s, while a priest at St. Pius X Catholic Church in Coeur d’Alene, Bill found himself confronted with the misuse of theology for hateful aims by white supremacists settling in northern Idaho. As chair of the Kootenai County Task Force on Human Relations, he lived through the bombing of his home and built coalitions to battle the racist Aryan Nations. After leaving Coeur d’Alene and the priesthood, marrying, and settling in Seattle, Bill continued his successful activism as director of the Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment.

In his book Hate Is My Neighbor, written with Tom Alibrandi, Bill said, “To ignore hate groups, even though they usually include relatively small numbers of people, is to miscalculate the impact that they can have on a community.”

When Bill died in 2002, then-Idaho Governor Dirk Kempthorne stated, “Bill Wassmuth was a bright beacon in the gloom of hatred and evil.”

One of Idaho’s great human rights heroes, he became the nemesis of those who preached hate. As one source of our inspiration, Bill Wassmuth reminded us that hate wins if we cower in silence.

In her diary, Anne Frank questioned, “Who has inflicted this on us? Who has set us apart from the rest? Who has put us through such suffering?”

My coworkers at the center and I had to ask a similar question. Who had inflicted this vandalism? Who had felt emboldened enough to enter the symbolic heart of the city to target and demean members of our city? Boise Police Chief Bill Bones declared the act a hate crime, and Senators Cherie Buckner-Webb and Chuck Winder stood in the memorial and denounced the act as “evil in our community.”

Why us?

Anne Frank. Wassmuth Center for Human Rights.

Visitors read plaques at the memorial. Steve Bunk photo.

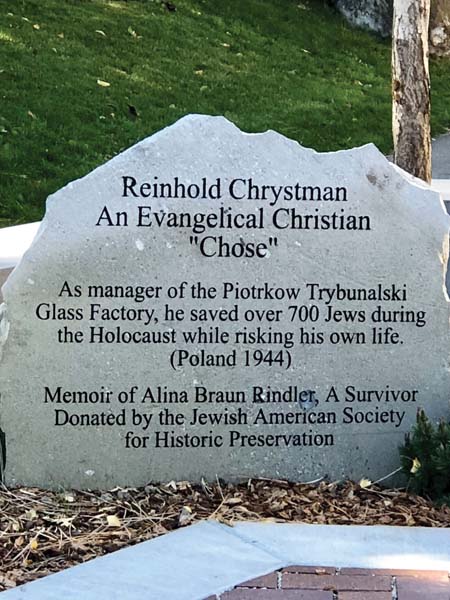

The Chrystman marker. Wassmuth Center for Human Rights.

An open-air classroom was added to the revamped memorial. Andy Erstad photo.

Water features of the park. Diesel Demon photo.

Detail of Anne Frank statue at the memorial. Kenneth Freeman photo.

Outdoor seating in a placid environment. Kenneth Freeman photo.

Dan Prinzing (center) holding Congressional Record remarks, with Idaho politicians. Wassmuth Center for Human Rights.

This is the only Anne Frank memorial in the United States. It’s one of the few places in the world where the entire text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is on public display, and it is recognized by the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience as an official Site of Conscience.

Annually, more than 120,000 visitors interact with the memorial’s message, and about ten thousand K-12 and university undergraduate students participate in free docent-led tours.

In the National Geographic Society book, Etched in Stone: Enduring Words from Our Nation’s Monuments, Ryan Coonerty wrote in a profile of the memorial, “Anne Frank could scarcely have conceived of Boise, Idaho. Therefore, it seems improbable that the author of a diary that has become among the world’s most widely read books has become a symbolic fixture of this community almost sixty years after her death.”

To showcase the memorial’s message, more than eighty quotes are carved into its stone, some of them from Anne’s diary and others from human and civil rights advocates throughout history, including one thought from Confucius’s teachings: “What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.” That idea is what the memorial reinforces, and it’s why the Wassmuth Center’s programming is used in classrooms and communities throughout the state. It’s what we stand for.

This year, we posed the national reporter’s question to Idaho teachers and memorial docents who attended the center’s Summer Institute, titled, “The Power of Words.” Held in partnership with Echoes and Reflections, a nationally recognized resource in Holocaust education, the Boise event called on educators to reshape the way they understand, process, and navigate the world through the tragedy of the Holocaust. So, we asked them, what did it say about our community when, under cover of darkness, the memorial was defiled by hatred in the form of vile and vicious words?

Participant Laurie Weatherby gave a revealing reply. “When this act of ignorance occurred, my first thought was, ‘Here we go again: another reason for outsiders to think Idaho is filled with racists.’ I still remember when I was in middle school and Idaho was looked upon as the racist state because of the white supremacists setting up a neo-Nazi headquarters on a compound in northern Idaho.”

She added, “As an educator, the vandalism reminded me of how much work still needs to be done to educate for the future—and to remind students of how we have more similarities than differences.”

Our discussions during the institute reinforced that the Holocaust did not begin with gas chambers. It started with words that demeaned and targeted members of the community. The words had power then, and they still do. It’s why the center emphasizes that words matter, and that they can be used as vehicles to divide or unite a community.

“When confronted with hate and antisemitism, the Treasure Valley is trying direct discourse rather than sweeping our less flattering history under the rug,” Alaina Sayers Huhn told participants. “I credit the youth in our state with driving this. It is incumbent upon educators to foster and normalize respectful dialogue from an early age.

“The power of words is the ability to build or break relationships, create or destroy connections, and foster or impede understanding,” she concluded.

“Actions speak louder than words,” Melissa Thompson pointed out. “I believe that the actions our community took after the vandalism show who we are. Within days, groups sprang into action to condemn these awful acts, and raised thousands of dollars to repair the damage. This is Boise, a community that speaks through actions and fosters acceptance, empathy, and hope.”

It’s true. Within weeks of the vandalism, more than $68,000 had been donated to repair and replace the damage—which occurred even while the center was launching a $1.7 million campaign to expand the memorial, to add the Marilyn Shuler Classroom for Human Rights, and to seed the Wassmuth Center Endowment in the Idaho Community Foundation. The classroom was built and dedicated in 2018.

Marilyn Shuler (1923-2017), a co-founder of the nemorial and board member of the center, was a longtime human rights leader and advocate in Idaho. Her many accomplishments and service included a twenty-year career, from 1978-1998, as director of the Idaho Commission on Human Rights.

I remember shortly before her death, Marilyn told a room filled with center supporters, “We ask something of each visitor to the Idaho Anne Frank Human Rights Memorial: to come, to learn, to read, and then to think about what you see. It’s in that thinking about human rights that we find the solutions and the courage we need to make Idaho a good place to live for every one of us.”

When she died, former Idaho Governor Cecil Andrus said, “Marilyn Shuler was our moral compass in the ongoing fight to ensure that all people are treated with respect, dignity, and compassion, as the law and the Constitution demand.”

Marilyn’s legacy reminds us that it takes courage to stand up to hate. Courage is a theme that weaves throughout the memorial. In each quote and every idea, we see the profound power of a single voice or bold action to overcome great odds and alter the course of history.

In his book Eight Habits of the Heart, Clifton Taulbert wrote, “Within the community, courage is standing up and doing the right thing, speaking out on behalf of others, and making a commitment to excellence in the face of adversity or the absence of support.”

I admire that theme in the memorial on a rock dedicated to Reinhold Chrystman, an evangelical Christian glass factory owner in Poland who saved seven hundred Jews. The donor who placed the rock, a descendent of one of those survivors, asked that a single word be highlighted on the rock to show what he did: “Chose.” Reinhold Chrystman made an intentional choice to stand up to hate.

“Boise is a welcoming city with a growing and diverse population. The existence of the memorial is a testament to the values that members of this community share,” Idaho educator Ben Harris told institute attendees. “Evidence of the importance of this space can be found in the engraved bricks, plaques, and benches with the names of community members, businesses, and organizations that passionately believe in the positive messaging of the space. It’s a space where people gather for dialogue, reflection, and celebration.

“These acts of vandalism demonstrate exactly why the memorial and the Wassmuth Center exist: to cultivate human sensitivity to past events and educate on the importance of human rights for all.”

As memorial docent Bill Brudenell put it, “Idaho is defined by upstanders, not by hate and antisemitism.”

Bill’s choice of the word “upstander” was not accidental. The Wassmuth Center defines an upstander by four qualities. First is a defender, an advocate and supporter of human rights and dignity. Second, a recognizer of the need for empathy, dignity, and compassion. Third, a person who acts when witnessing inequality, injustice, and oppression. Fourth, someone who recognizes, engages, and empowers others to confront injustice.

Bill reminded us that since the memorial was dedicated to the public in 2002, “There have been acts of hate against the LGBTQ and Jewish communities, people of the LDS faith, refugees, and Latinos. All acts of hate have been countered by Idahoans standing up in public demonstrations and writing letters to the editors of local newspapers and to our members of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate. We all realize that our work for human rights is never done . . . . We must never forget the power of words to prevent the Spiral of Injustice.”

The Spiral of Injustice is showcased in the memorial’s electronic kiosk and depicted in a statue of “The Other,” an individual who is perceived as not belonging, as being different in some fundamental way. The spiral illustrates how injustice devolves within a community. Its first level is language: when the Other is targeted through word choice, name-calling, ridicule, jokes, belittling, and stereotyping. The Other often is targeted because of association with a group based on class, race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, ability, or religious preference.

Once dehumanized, that individual is subject to avoidance, discrimination, violence, and even elimination. We at the Wassmuth Center focus on the language used in such circumstances, and we advocate that the Spiral of Injustice can be interrupted by an upstander’s words and deeds.

It’s a choice that takes courage.

The memorial recalls a young Pakistani girl who defied the Taliban and demanded that girls be allowed an education. The words of that young person, Nobel Peace Prize-winner Malala Yousafzai, resound: “When the whole world is silent, even one voice becomes powerful.”

When I joined the institute participants on a tour of the memorial, we paused to read a quote from Martin Niemoeller, a Lutheran pastor who opposed Hitler’s attempt to mold the Christian faith to suit Nazi ends: “In Germany they came first for the Communists, and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a Communist. Then they came for the Jews, and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a Jew. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I didn’t speak up because I wasn’t a trade unionist. Then they came for the Catholics, and I didn’t speak up because I was a Protestant. Then they came for me, and by that time no one was left to speak up.”

“The memorial is a sanctuary that was built by community members, is maintained by community members, and when damaged by the deplorable actions of a vandal (or vandals), was repaired by community members,” Keith Watkins noted during our summer gathering. “This attack was deviant, not only in its criminality, but it is a deviation from our values as a community. That the memorial is in Boise, our state’s capital, shows a united stance against hate—a united community in support of all members of our human family.”

Following the acts of vandalism, Idaho Senator Mike Crapo entered this statement into the Congressional Record: “Rather than responding with anger and hate, Idaho is moving forward with a positive spirit of renewal and inclusiveness.”

All this explains why when the reporter asked what an act of hate said about Boise, my reply was a request that she not judge us by the vandalism, but by the community’s response to it. Anne Frank said it best: “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.”