No products in the cart.

Stanley–Spotlight City

A View of the Sawtooth and White Clouds Mountains Defines This Central Idaho Village

By Ryan Peck

The view from Stanley is the type of image you find framed and prominently placed on the walls of offices all over the world. It is not hard to imagine an overstressed cubicle dweller taking a moment of reprieve from stacks of work to gaze at such a picture. You know the kind: jagged, snow-capped peaks, a free flowing river, and the sunlight hitting everything just right. Famed photographer Ansel Adams made a career of that kind of western mountain image. These pictures are relaxing because they serve as reminders that somewhere beyond the concrete confines of larger cities, there exists a place like Stanley.

Just as a photo of the Stanley view may provide stress relief for urban office workers, the real Stanley and the surrounding areas provide stress relief for visitors in a number of other ways. River recreation is one. For Middle Fork of the Salmon River floaters, and those who raft other central Idaho rivers, Stanley is the place to pick up supplies before the trip. For example, Stanley business proprietors Christy and Charlie Thompson, owners of the Riverwear store, have had many river rafters drop in on them in the early a.m. to stock up on fleece before a trip. Christy Thompson said, “People are glad to see we have so much warm stuff in our store … not everyone realizes how cold it can get up here, even in July.” If you are an angler, Stanley offers up the surrounding high mountain lakes, Valley Creek, and the bustling Salmon River–all brimming with trout species. Fat tire mountain bikers come to Stanley for incredible rides such as the Fisher Creek Loop. Hikers wear holes in their socks all over the Stanley Basin’s backcountry wilderness, from Alpine Lake to Imogene and beyond.

Then there’s the big chill in Stanley.

Hardy winter enthusiasts are able to find hundreds of miles of trails to navigate with snowmobiles or cross-country skis. Backcountry skiers earn their turns in abundant untracked powder from the Williams Creek yurt or simply tracking into Stanley Lake. Even the stressed-out city slickers finally make it to Stanley (as opposed to settling for a picture on a wall) for some much-needed “R’n’R” which means just hanging out and taking it all in for rest and relaxation. Oh yeah, and there are hot springs everywhere! Stanley means many things to many people, but everyone agrees on one aspect of the town: regardless of the season, it is gorgeous.

If you mention the town of Stanley to someone who has been there, you will, without a doubt, hear the word “beautiful” mentioned somewhere in the response. Nestled at the base of the majestic Sawtooth and White Clouds mountain ranges (more than forty peaks in the area exceed ten thousand feet), Stanley is the epitome of a rustic western town. The winters are long–and the temperatures are frequently the coldest in the Lower Forty-eight. “When it is 40 below, you stay inside,” says longtime Stanley resident Ken Klusmire. “When it is that cold, it even makes for a daunting trip to Ketchum [about sixty miles, mostly on mountain roads] in your car. If your car breaks down you are in trouble. I’d rather stay home. I like that cozy feeling when it is scary outside but cozy inside.” To defend against the frigid weather, nearly every Stanley resident has a wood-burning stove. Stanley’s buildings are almost all log structures done in a natural finish. Most of the roads in town are dirt or gravel. And the population is small, hovering somewhere right around one hundred. “The town is so small, it nearly shuts down when someone goes on vacation,” Stanley Chamber of Commerce Clerk Rocky James said. If anyone does decide to get out of town (maybe to remind themselves of the city stresses), there are three ways to choose: Lowman to the west, Ketchum to the south, and Challis to the north. The nearest town in each case is approximately sixty miles.

Rafting the Upper Salmon River near Stanley. Ken Klusmire photo.

A snowmobiler catching some air near

Stanley. Paul Frantellizzi photo.

Idyllic Stanley. Paul Frantellizzi photo.

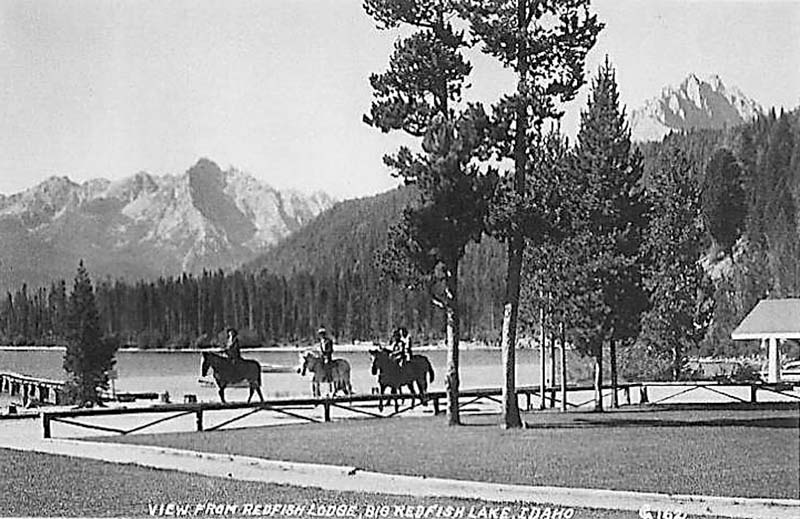

A look from the Redfish Lodge’s front lawn, circa 1940. Photo courtesy Kelly Yost.

The classic view of Stanley in its winter coat of snow. Paul Frantellizzi photo.

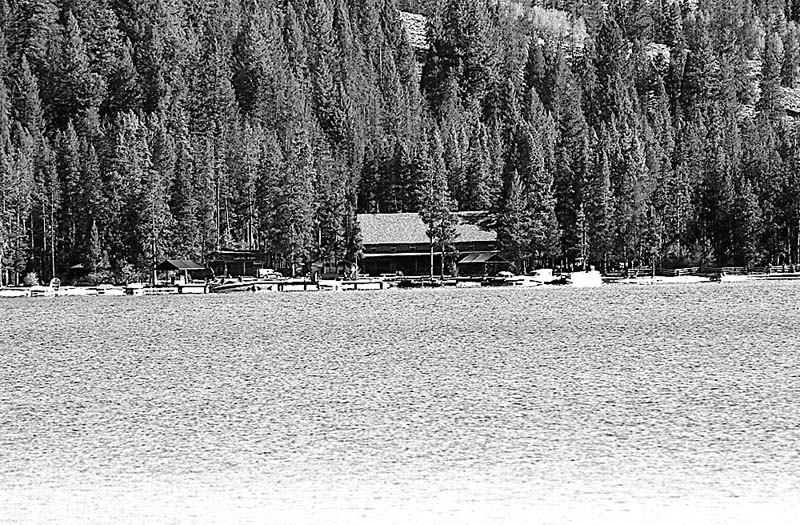

Redfish Lodge as seen from the lake. Kelsey Newman photo.

Stanley’s “Mountain Mamas” take a moment to relax. City of Stanley photo.

The Sheepeaters, Gold Mining, and Homesteaders

After the last ice age finished the job of carving out the Stanley Basin, people showed up. About ten thousand years ago, prehistoric hunters who lived in the area may have enjoyed the scenic splendor of the basin at times while carving out a primitive existence. A few thousand years later, a group of Shoshoni Indians called the Tukudeka (Tookoo-dee-ka) occupied the area. Literally translated, Tukudeka means Sheepeater. The Sheepeater Indians’ diets, however, consisted of more than sheep. They also subsisted on the plentiful salmon runs that filled the Salmon River and surrounding drainages. The Sheepeaters lived in the area until the latter part of the 19th Century, when the United States Cavalry transported them to the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in southeastern Idaho. For some great historical reading on the Sheepeater Indians, check out Middle Fork and Sheepeater War: A Guide by Idaho authors John Carrey and Cort Conley.

It was also in the 19th Century, albeit the very beginning of the century, that Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery (1803-1806) brushed past the Stanley Basin on its way to the Pacific Coast. The explorers stayed long enough to give the new name “River of No Return” to the Salmon River. They gave it the new label for two reasons: one, it wasn’t getting them to their destination (the Salmon River actually flows in an easterly direction outside of Stanley), and two, the Salmon River has some rough rapids.

Fur trappers looking to fuel the fashion trends that favored beaver pelts soon followed westward explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Alexander Ross, who worked for the Hudson Bay Company, led the first trapping party to the area. Ross and company crossed Galena Summit on September 18, 1824. If you ever make the drive, stop and check out the roadside marker commemorating the trip. By 1840, the winds of fashion changed, and the beavers were depleted.

Twenty or so years later, gold seekers started appearing. In the mid-1800s, all you had to do was exclaim “Gold!” and one thousand or so people would immediately show up. Placer gold in what would later be named the Stanley Basin was first found in 1863, the same year President Abraham Lincoln signed the congressional act that created the Idaho Territory. A year later, Civil War veteran John Stanley led some miners into the basin that would bear his name. Stakes were established and people went about the business of striking it rich. The Sheepeaters, the cold, and shortages of much-needed supplies eventually deterred these miners from the area.

A decade or so after Stanley and friends left the basin, miners returned with new fervor. Not only did they find gold, they found silver. A supply center was opened and since everyone liked long-gone John Stanley so much, they named the supply center after him. Other towns sprang up in the area and began booming. When you make it to Stanley, visit the nearby ghost towns of Custer and Bonanza. In their heydays, those towns each had populations of more than five thousand. The arrival of so many gold and silver seekers coincided the demise of the Sheepeaters. The Sheepeater War was kicked off when five Chinese miners were killed in 1879. Nobody could actually prove it was the work of the Shoshoni tribe, but the U.S. Cavalry was called in, and a war began. Eventually the Sheepeaters were rounded up and transported to the Fort Hall Indian Reservation.

If you visit Stanley today, you can still occasionally see someone panning for gold. A gentleman with a long white beard and dirty jeans told me that if you know what you are doing, you can make a living panning for gold. In fact, this is how he claimed to make his income. Once the fast gold petered out, the populations did, too. This was not, however, the end of industrial mining. For proof that the practice continues, drive up the Yankee Fork and check out the dredge.

Homesteaders and sheepherders both showed up at the turn of the(last) century. The people who chose to call the Stanley Basin home were hardy souls. Because of the harsh environment, many ranches were abandoned.

The Stanley Stomp

With the advent of roads and the nascent contraption called an automobile, people came to Stanley because it was an outdoor recreation destination. Even so, for many decades Stanley retained its Wild West persona. Emphasis is on the word “Wild.” Shootouts on Stanley’s Main Street were recorded as recently as the 1970s. Selma Lamb recounted the story of the lady who set up shop across the street from the town’s main bar. “Judy Smith used to own a hardware store across from the Rod and Gun Saloon. She would get her fence knocked down every week because of the fights!” And then, of course, there was the popular Stanley Stomp, which took place down at Stan Harrah’s Mountain Village (Riverwear now occupies the space). “You could start the night at whatever bar you wanted . . . and you could walk around town with the same glass from place to place. On Sunday mornings the Stomp would take the glasses back to the right bars,” Lamb told me.

One of the beauties of the Stanley area is that the landscape remains essentially timeless and unchanged. Federal legislation passed more than thirty years ago made it so: in 1972, the Sawtooth National Recreation Area (SNRA) was created, bringing a federal designation to a little more than 750,000 acres of Stanley Basin land. The SNRA spared the Stanley Basin from the destruction of land misuse and overpopulation that some had feared. In a sense, because of the legal impediments that largely block growth, Stanley is not going to get any bigger. Simply put, there is little private land available in the Stanley area.

Today, about one hundred hardy souls call Stanley “home” year-round. The size of the town increases to a few hundred in the summer. The village has two main grocery stores, a post office, and some hotels. Now missing from the town are amenities such as banks and movie theaters. Selma Lamb offers her insight, “There are no movies, swimming pools, or video games. To do well in Stanley you have to be an outdoor person. People that aren’t only last a certain time and then they are gone.” When I asked her son Lloyd (now in his 30s) what it was like to grow up in Stanley, he said, “Let me tell you, I didn’t know I was so alone because of all the imaginary friends I had. No, really, there were other kids, and we were all friends. It didn’t matter what clothes you wore, what sports you liked, or what your parents did for a living, we were all friends.” He added, “We always played outside, even in the winter! Our parents would kick us out of our houses to go play as long as it was at least zero degrees outside.”

Yeah, it’s the winter life that really takes some adapting. If you ever make it to Stanley in the winter, you may wonder where the houses went. It seems that most of the town’s dwellings get buried under about five hundred cords of firewood. But, it is during the winter that Stanley offers the most solitude. Frequently Highway 21 to Boise closes due to avalanches, and the number of people coming up to visit the town decreases a bit. But the winter days and nights can be incredible. I have gone to Stanley in the winter . . . I spent my days cross-country skiing and then I spent my evenings relaxing with friends in the hot springs. The stars are so bright you don’t even need headlamps. Klusmire offers his take on winters in Stanley, “At first I thought I would go nuts. But then I relished the solitude. The winter was just long enough that by the end of it I was ready for the tourists and interaction.”

In summer, the town triples in residents and thousands of tourists come through. Christy Thompson told me with a laugh, “I think more friends and family visit us in Stanley than they did when we lived in Twin Falls or Salmon. At first I thought it was because they wanted to see us. Now I think that is only partly true.”

The winter/summer dichotomy strains many Stanley area businesses. You go from working seven days a week in the summer, to having to close down in the winter or operate only a few days a week (in fact, the city library only opens for three days a week in the winter). The seasonal population shift also puts a strain on available housing. It isn’t uncommon for raft guides and other seasonal employees to choose camping-out for the summer. Longtime river guide Jared Goodpaster said, “When I first started guiding I would just camp out. It was the most beautiful bedroom I have ever slept in. The only problem I had was coordinating sleeping in the tent with rain . . . It seemed like whenever I would go sans tent it would pour on me.”

Looking to the Future

Leadership has been changing. Stanley got a new mayor a few years ago named Paul Frantellizzi. A longtime friend of the Lambs, Frantellizzi came to Stanley to escape the stresses of life in New York City. What he found was a beautiful mountain community to live in. Frantellizzi’s job, along with the Stanley City Council’s, hasn’t been easy. Stanley faces what officials view as an incredible number of federal mandates. In addition, there are the issues of affordable housing, tourism pressures, and town unity. They say that it is easier to lead a large group of people than a small group, but Frantellizzi, along with residents of Stanley, are working hard to take the town into the future without losing what makes Stanley great in the first place. But it is not just the political leadership that is changing in Stanley; it is also the business owners. Many of the businesses in the valley have changed hands in the last few years. With new ownership comes new enthusiasm and change. But one thing that will not change is Stanley’s beauty.

And one highlight mirroring the natural beauty at Stanley is Redfish Lake.

The Magic of Redfish Lake

Redfish Lake, as natural science shows us, has been around for a long time. No doubt, the Sheepeaters and other historical inhabitants appreciated the lake’s beauty and the resources it provided. Beyond that, settlers started coming to the area en masse when roads were completed over Galena Summit in the 1920s. In 1920, B.D. Horstman built a hotel and boating facility on the lake. Bob Limbert in 1929 kick-started the tourism business at Redfish Lake. Limbert did that by expanding the lodging and boating infrastructure to what it is today. He was also good with words, saying of the Redfish Lake area, “… In places like these, one may sit entranced for hours at a time, for it is impossible to exaggerate the grandeur, the sublimity, and the impressiveness of the place. Its fascination cannot be accurately described. It is a land of a thousand different moods and no one can know it for what it is without living in it for every day of the year.”

Over the years, Redfish Lodge has changed hands eight times, and it’s said that each owner has worked diligently to improve the hospitality and beauty of the area. The Crouch family from southern Idaho now owns the resort. Today, it’s a 16.8-acre resort. On the premises are forty-one rooms and cabins, a restaurant, a bar, marina (with new docks), a fleet of Redfish-owned boats, and an on-dock service station. Redfish is one of the most photographed lakes in the nation. Longtime human resources manager Kelsey Newman offers her take on Redfish: “It is an unforgettable, magical, family place. It feels like a second home in the mountains. You immediately feel like you are part of the family.”

Rafting the River of No Return

Rafting is a quintessential Stanley activity. Four commercial companies that offer trips on the Upper Main Salmon River right outside of Stanley: The River Company, White Otter, Sawtooth Adventure Company, and the company formerly known as Triangle C (it was recently purchased by a new owner–new name to be announced). These companies run four major rapids on the Salmon River including the class IV rapids Shotgun and Sunbeam Dam. Folklore has it that Shotgun Rapid was named when two early Stanley residents (presumably miners) lost a shotgun in the rapids. Among rafters, the rapids name refers to the way it tends to launch passengers and guides into the air. Longtime guide Lloyd Lamb offers his insight: “It looks fairly harmless but there are some hidden obstacles that will launch you in the air … they don’t call it shotgun for nothing. Next thing you know you are married to the water, you know, like a shotgun wedding.” Shotgun was featured in a Milwaukee’s Best beer commercial in the 1970s. Sunbeam Dam or “The Dam” as guides call it, is one of the more novel commercially run rapids anywhere in the world. “The Dam” is an old blown-out dam. Built by the Golden Sunbeam Mining Company in 1910, the dam was engineered to power a gold mine up the Yankee Fork. Shortly after the dam’s completion, however, the mine went bankrupt. In addition, the dam was blocking the migration of Chinook and sockeye salmon upriver (salmon were so plentiful at the turn of the century that a cannery was once considered for Stanley). If you ask a guide what happened, he or she will tell you that some locals got together and loaded a small boat full of dynamite and sent it out on the reservoir toward the dam. The boat got washed up on the southern shore, and rather than the dam getting blown up, the entire shore was blown out. Other stories recount the effort as being done in a more formal fashion by state employees. Either way, the river was reopened in 1934.

The Mountain Mamas Having Fun, Helping Out

The Mountain Mamas are a group of local ladies who, though no one directly admits it, run the town of Stanley. The only requirement for membership is that you are a woman. Once the second x chromosome requirement is met, the Mamas don’t exclude members for any reason. You don’t even have to be a mom. Membership ages range from 20-somethings to women in their 80s.

The Mamas have been around for more than a quarter century. “I have been a Mama for as long as I can remember,” says Selma Lamb.

The Mamas’ greatest success is putting on the fantastic Mountain Mamas Arts and Crafts Festival every third weekend of July. The festival ranks among the most diverse and successful arts and crafts fairs in the state. This year the group offered 140 booth spaces and sold out in a week. The Mountain Mamas also put on a September quilt festival and a Christmas cookie party.

The Mamas are predominately a service organization. Lamb says, “There are no dues; the main requirement of membership is that you are able to work at the fundraisers.” All of the funds raised by the Mamas are donated to public interest causes. The causes have historically included the Stanley School, Fire Department, The Stanley Meditation Chapel, and the Stanley Library.