No products in the cart.

The Plumb Simple Radish

By William Studebaker

My neighbor Tom told me, “It’ll be another couple weeks before we can start farming. We don’t even plant beans until late May or early June.”

Well, I don’t farm, but I do raise a small garden. It’s tucked away in a flowerbed. I don’t raise much, just simple plants.

Take radishes for example. They’re simple. They’re the type of vegetable I can keep domesticated. Carrots I can handle, too. I won’t try anything as complicated as corn or beans. And potatoes about kill me.

Once, out of my mind, I thought about raising colicroots, but I don’t do herbs well. I like docile plants. They do what you tell them, and they don’t get ideas on their own.

Corn’s just a high-rise for earwigs. A bean’s too sociable. It’ll intertwine with its neighbors, and pretty soon the whole damn row is all snarled up. I won’t weed if I have to fight runners or rhizomes.

No siree, the radish is for me. Just stick some seed in the ground, let it sprout, water a bit (warm them up, cool them down), and then start thinning. Like carrots, you can eat while you thin. That’s a bonus.

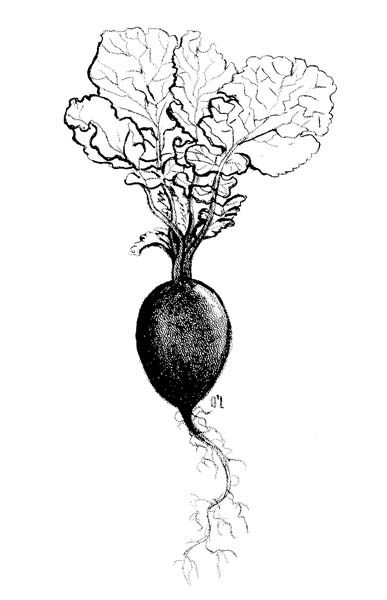

Dick Lee illustration.

If you thin too much, and don’t take particular care, a radish will get big and split inside. Once it splits, it’s pithy. A pithy radish makes a poor salad enhancer.

A radish should have a solid red skin, and with a light scrubbing, glow like a ruby.

Inside, its meat should be white, firm, and moist. The heart should be dense and crisp. Every bite should snap; every snap should radiate a vegetable warmth.

For those with frail, fragile, immature, or just bland taste buds, the radish is a challenge. It’s not horseradish, but it’s a step above cabbage’s kissin’ cousin kohlrabi and two steps above a rutabaga. It’s a real threat to a green onion, too.

An onion has a pedestrian taste, while the radish effervesces. Its regal aroma is a whiff of delight. All of the bonuses aside, it’s the simplicity of the radish that attracts me. I don’t mean simple if compared to a sequoia. I mean simple artistry and simple husbandry.

I mentioned radishes to Farmer Tom, and he said, “Skunks.”

“Skunks. What do you mean skunks?” I said.

“The skunks are coming out. Soon the little ones will be everywhere. And when they’re everywhere, it’s spring. Then, you can plant your radishes.”

“Oh,” I said. “I thought you were comparing radishes with skunks.”

“Nope. I know the difference. One smells a little stronger than the other. How about you?”

“Of course I know the difference,” I said. “The radish is a sweet thing.”

As easy as it is to raise radishes, I can’t help myself. I make it difficult. I choose one each year as a pet.

Now this is the point: choosing a pet radish isn’t as simple as raising a row of the little beggars. The idea is to pick one that’s uniform, nice, and bulbous, with a supple, red skin. Its taproot should be long and energetic. But even more important than being firm of body, it should have a sweet spirit and a willingness to lean toward the sun.

I play compositions by William Billingsley, one of Idaho’s great composers, to my pet radish. The music soothes and stimulates.

When my pet is absorbing water filled with delicious nutrients, I play a “Fantasy for Flute.” Then, I let it climb out of its slumber to the stimulating mix of “Landscape Sketches.” And with the deep, prolonged strum of the piano strings, it grows as if the distant horizon were its goal.

That’s some aspiration for a radish.

Well, Farmer Tom and I know what should be done with a pet radish. It should be taken to the county fair. But radishes are spring and early summer critters, and by late summer, they’re all pithy and hot and gone to seed (bad seed by late August). The fair is for pickled beets, zucchini, squash, watermelon, and the frilly fruits.

So, a pet radish, as if it were a pet head of lettuce or a pet clump of watercress or a pet goat, gets eaten. Like no other pet, it can transport a salad from the profane to the sublime and cause the palate to tingle with culinary passion.

The pure, natural joy comes from careful nurturing, thus making the gardener’s love, the gardener’s delight . . . and that’s the right way.