No products in the cart.

The Middle of Nowhere

Sounds Good to Me

By Tom Lopez

As a child, I received many Christmas cards from Idaho at our home in Michigan. The first one I can date with any certainty, which arrived when I was eight years old, contained a vivid description of the massive 1959 Hebgen Lake earthquake that shook Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana. There were earlier cards, each of which presented a slice of Idaho life and each of which contained a crisp one dollar bill. The author of those cards was my Great-Aunt Ethel Masters.

My mother was orphaned at an early age. Her father died from sepsis in a time before antibiotics. Her mother died in an automobile accident in a time before seatbelts. Her life after these tragedies was, in a way, Dickensian. She was passed around among relatives. For a period, she lived with a strict Methodist minister and his wife. Her younger sister was adopted by one of the richest families in Logan, Ohio. A shining light in this dreary portion of her life was her mother’s sister, Ethel.

Long before I reached the age of awareness, Ethel had left Ohio to live in Idaho, a place my mother referred to as “the middle of nowhere.” When I asked at age six where the middle of nowhere was, she replied, “It’s no place for you.” I’m not sure what motivated that response but it didn’t square with the yearly news from Ethel.

Her Christmas cards contained long dissertations on the past year’s Idaho events, which my mother would read to me. The tales contained in those letters made the middle of nowhere sound appealing to an adventurous kid. The stories described a land of volcanoes and earthquakes, of bears and cabins in the mountains, of floods in the spring and rabbit infestations in the fall, of blazing heat in summer and freezing blizzards in winter. Long before I crossed the Idaho border and met Ethel, I fantasized and dreamed of the adventures I might have one day in the middle of nowhere.

During a summer break from college in 1971, I made a trip to Montana with a friend. Relieved that I survived, my mom wrote to Ethel about my trip and she immediately wrote back, demanding that if I ever returned to the West, I must visit her in Idaho Falls. For the next year’s summer break, I decided on a grand tour of the western states. I had three definite stops on my itinerary: the Grand Canyon, Mount Whitney in California, and Idaho Falls. After hiking across the bottom of the Grand Canyon and scaling Mount Whitney, I was ready to meet my aunt. Tired of hitchhiking, I bought a train ticket from Reno, Nevada to Ogden, Utah. I arrived at the Ogden train station early in the morning, walked to the bus station, and bought a ticket to Idaho Falls. On the way, I sat beside a young Mormon woman who told me about her faith and a bit about the country we were passing through. In Idaho Falls, I called Ethel and introduced myself. “Don’t move. I’ll be right there,” she said. She arrived fifteen minutes later.

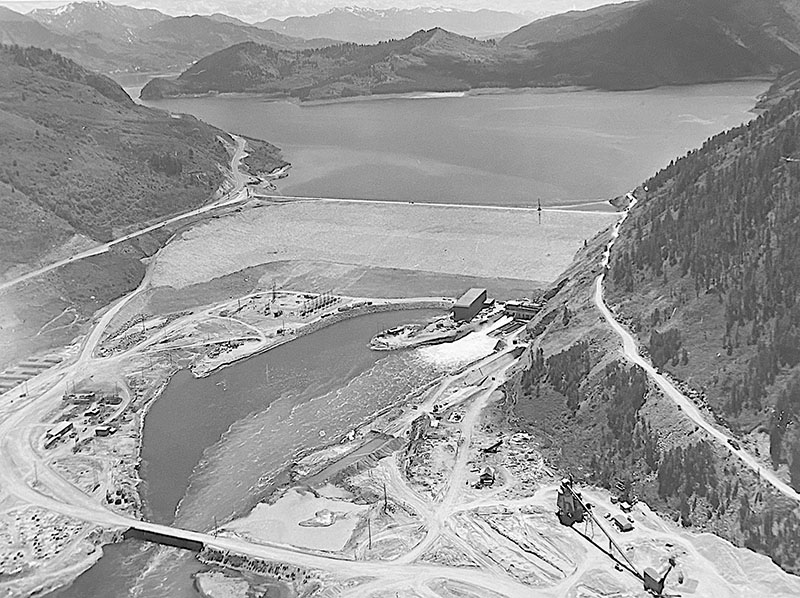

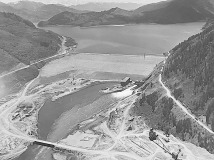

Constructing the outlet tunnel. Bureau of Reclamation photo.

Ethel Masters at the farmhouse. Tom Lopez photo.

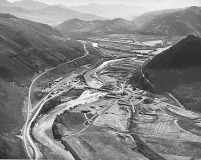

Falconberry Ranch, 1937. University of Idaho photo.

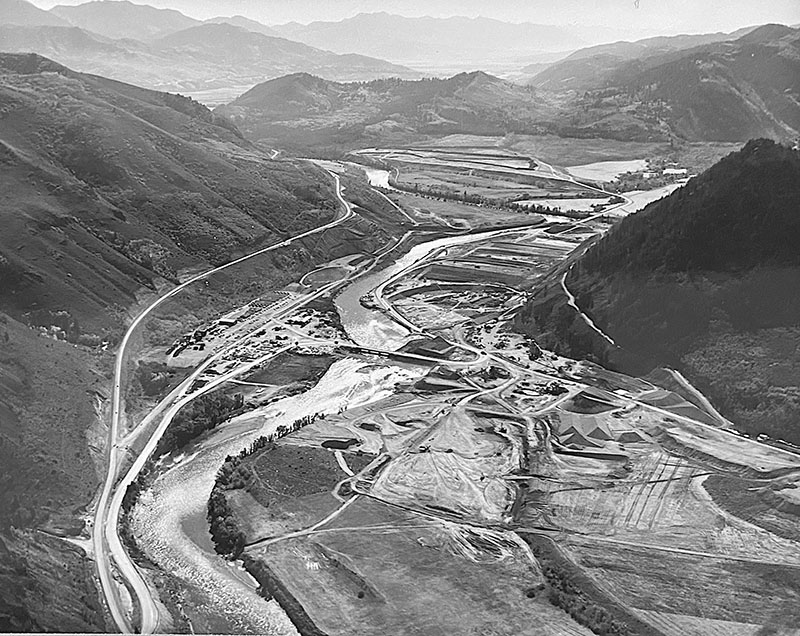

The finished Palisades Dam. Bureau of Reclamation photo.

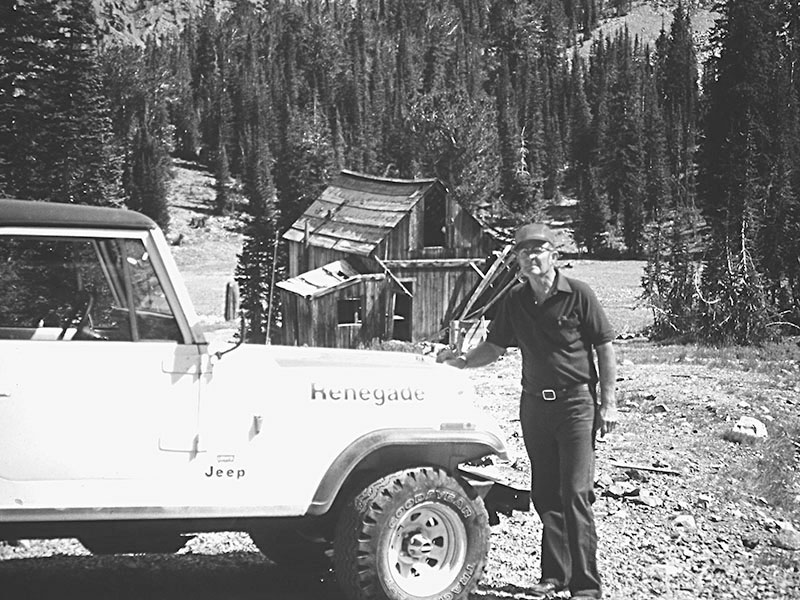

Paul at Boulder City. Courtesy the Masters family.

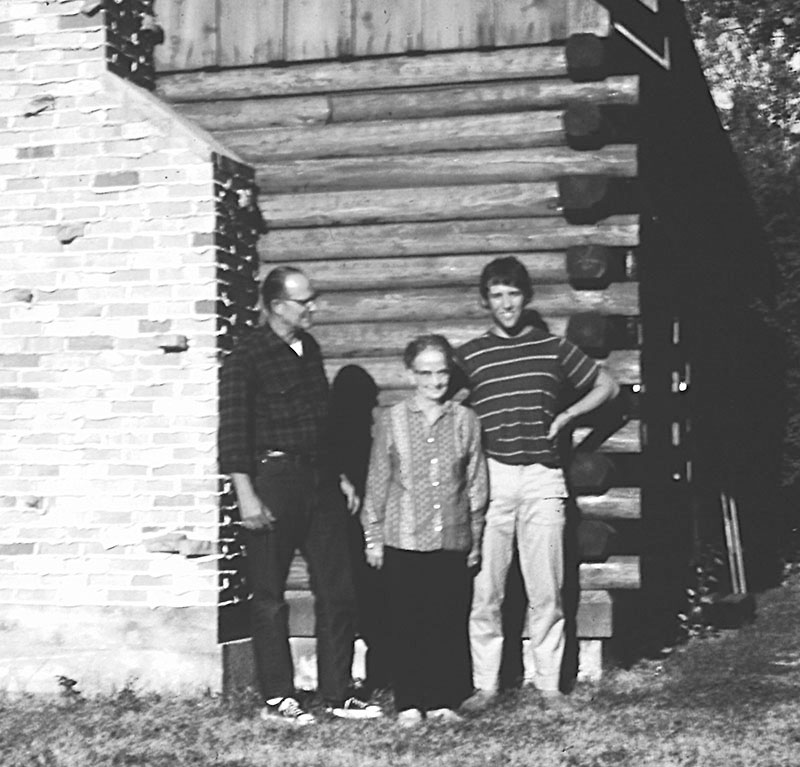

Paul, Ethel and Tom at the cabin, 1972. Judy Masters photo.

The dam construction site. Bureau of Reclamation photo.

I had never met my great-aunt and my mother had not set eyes on her for more than thirty years. That didn’t matter. We were family. For the first time in my journey, I had nothing to worry about. When Ethel’s husband, Paul Masters, arrived home to find a stranger in his house, he was perhaps a bit suspicious. In the entire time they had lived in Idaho, no one from Ethel’s family had visited.

When Ethel introduced me, his response was, “Lopez. What kind of name is that?”

“It’s my name,” I said.

As it turned out, Paul would play a big part in my life for the next fifteen years.

Paul and Ethel had moved to Idaho Falls after World War II. His sister had married a successful Idaho Falls doctor, John Hatch. Ethel, a nurse, worked in Hatch’s office and Paul managed the doctor’s dairy farm and his dude ranch on Loon Creek, in what was then called the Idaho Primitive Area. By 1972, Ethel was retired and Paul was near retirement. Long before I visited, they had built a cabin on a high point above Palisades Reservoir. While the word “cabin” brings up visions of a small, dank structure in the trees, this cabin was anything but. The cabin was a meticulously put together log structure with a large brick fire place, four bedrooms, and a full bathroom. The main living area, centered around the fireplace, included the kitchen and gave mountain views through two large picture windows. There was a two-car garage and an outhouse that Paul had bought on surplus from the Bureau of Reclamation. Like the cabin, this facility was a significant upgrade to a standard outhouse. Paul called it the FDR, in honor of his favorite president.

The two weeks of my visit constituted my introduction to Idaho, during which Paul took over the storytelling duties. Like Ethel’s Christmas cards, each story he told kindled my desire to explore the state my mother had once told me was “no place for you.”

Paul was a master of everything he undertook. He was born in Selma, Alabama in 1908. It was never clear to me how he and Ethel met but no doubt it was while he was traveling for work. Paul was proud of his diverse work history. During the Great Depression, he worked for the railroads, specializing in the management of refrigeration cars. He spent the World War II years troubleshooting transportation bottlenecks, a job classified as essential.

One of his favorite work stories was from the second winter of the Depression, when he was on assignment for the railroad in Twin Falls. He always set up this story by recalling how bad the times were for many people. While he was eating by himself in a restaurant, a rather disheveled man came through the front door. Rather than looking for an open table, the man walked to the wall where the customers had hung their hats and coats. He proceeded to try on the coats and hats. Eventually, he found a coat and hat that fit him and walked out the door. Paul, who had a rather offbeat sense of humor, laughed and ordered dessert. When he finished it and left, he realized that the man had taken his coat and hat. Every time he told that story, he laughed heartily.

When he moved to Idaho after the war, his brother-in-law put him in charge of his Idaho Falls dairy farm and his wilderness dude ranch. Paul became an expert in the dairy farming business. Years later, he still loved to expound on the importance of what a dairy cow is fed. It struck me that he tended to do this right after observing the softening waistlines of his fellow humans. When Idaho Falls grew eastward, it engulfed the farm. Dr. Hatch decided there was more money to be had in subdividing than in farming. Paul and Ethel still lived in the farmhouse when I arrived but the farm was gone and Paul had moved on to working as a fire protection engineer at the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory, today’s INL.

The wilderness ranch, Falconberry, was on land Dr. Hatch owned land along Loon Creek in what is now the Frank Church–River of No Return Wilderness. It was primarily operated as a dude ranch for rich eastern hunters. In 1980, Falconberry Ranch was purchased by the US Forest Service to prevent incompatible development in the wilderness area and to permit public access to about three miles of stream banks along Loon Creek. Hatch, who died in 1996, continued to use two acres and twelve buildings for the rest of his life.

Falconberry was reached by a rugged mountain road that penetrated deep into the wilderness. At the beginning of each summer, Paul would organize transport of horses and mules from the farm to the ranch, hire staff, and open the buildings. There were many stories about the dangerous roads, the cantankerous mules, and the characters he hired over the years. One of his most-admired employees was a cowboy everyone called Shorty, who came back year after year. He loved to tease and harass the dudes, which evidently made him not only Paul’s favorite but also, unlikely as it seems, popular with the dudes.

Each fall Shorty would lead hunters up to ridge-tops to hunt mountain goats, where he would advise them to dismount. One dude boasted he could circle the high-mountain cirque where Shorty dropped him on foot and return by lunch time. Shorty knew the dude wasn’t up to the task but said nothing other than, “Well, you might want to take a sandwich with ya.” Six hours later, Shorty mounted up and rode out to rescue the tenderfoot.

By the time I moved permanently to Idaho in 1978, Falconberry was no longer in operation. One fall I learned that Dr. Hatch was looking for a caretaker to spend the winter alone at the ranch. When I told Paul I wanted the job, he tried to dissuade me. I insisted but he said, “It’s not going to happen. You would go crazy back there by yourself.”

Paul accomplished a lot in his life, but I think his magnum opus was the cabin he built above Palisades Reservoir. The dam had been constructed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation for water storage and power generation in response to droughts that had occurred in Idaho concurrently with the Dust Bowl that punished the Great Plains. Calamity Point, a narrow passage along the Snake River east of Idaho Falls, was chosen as the dam site. According to a Bureau of Reclamation account, “The priorities of World War II delayed all progress on the project until 1945. Workers first built a construction camp for offices and housing. Next came the transmission line to carry electricity from the dam to the users. More than fifty miles of road were moved. Workers continued preparing the site and testing the earthen materials. Progress stopped each year when the harsh winter weather hit. High winds and excessive snowfall in February 1949 isolated the dam site for ten days.”

Despite the preliminary work, Congress did not reauthorize the project until 1950. Work started the following year, it was completed in 1957, and started producing electricity in May 1958. The Palisades Dam measures two hundred and seventy feet tall, twenty-one hundred feet long and twenty-one hundred feet wide from upstream to downstream. The material used, by volume, made it the largest dam built by the Bureau of Reclamation, including believe it or not, the Hoover and Grand Coulee Dams. Sixty-one years after its completion, the dam and generation plant were listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Dr. Hatch and Paul realized that one of the fringe benefits of the dam was the recreational opportunities it would bring. They purchased three adjoining lots on a descending ridge on the north side of the reservoir. Paul took the highest lot. They hired a man with a bulldozer to construct a road from the new highway up to the lots. Three cabin sites were carved out. Paul and Ethel soon started construction of their cabin. When I arrived for my two-week 1972 visit, the cabin was the focal point of their year.

I remember thinking how helpful and friendly people were in Idaho. Reading trumped television. Discussions of diverse topics were a main activity during get-togethers. Everything centered around the magnificent terrain.

In The Idaho Encyclopedia, a Depression-era Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration, the state was described as “a geographic monstrosity.” The authors’ explanation of this conclusion was, “Its shape and size were determined with no regard to what they should have been, but as a leftover area after the limits had been fixed in the states around it. In consequence, of all States in the Union, it has perhaps the least geographic logic and integrity within its borders.” On one hand, the more than sixty-five percent of Idaho’s 83,557 square miles that consist of mountain terrain divided by deep rivers have prevented Idahoans from developing into a homogeneous community. On the other hand, they have led to the creation of communities and regions worthy of a lifetime of exploration.

Looking back at my life of experiences in Idaho, where many of my childish fantasies more or less came true, my memories often unwind like a crazy dream. Vignettes are at once vivid and surreal. Occasionally, these memories seem downright improbable and I ask myself, “Did that really happen?” I also still wonder if the middle of nowhere is an actual location or simply a mythical place. It has been described as the “boondocks” or “rough, remote, and isolated country” and occasionally as “an out-of-the-way area considered backwards and unsophisticated by city folks.” But maybe it’s best to think of it as a place difficult to access mentally. As Bill Nye once reminded us, “We [on Earth] are just a speck on a speck orbiting a speck, in the corner of a speck, in the middle of nowhere.” From that perspective, the middle of nowhere could be anywhere and everywhere.

After nearly fifty years exploring Idaho, my search for the middle of nowhere continues to reward me.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Comments are closed.