No products in the cart.

Planting Fish

In Alpine Lakes

By Mary Terra-Berns

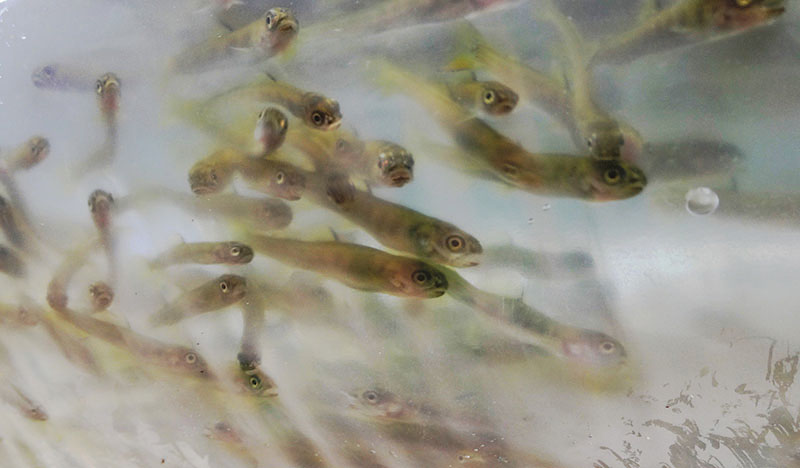

More than a thousand tiny fingerling trout travel in a plastic commercial milk bag full of chilled, oxygenated water tucked into my backpack. I stop on the trail above the lake for a quick breather and to take in the view of the Selkirk Mountains. My husband Tony and I have just released fifteen hundred of the little guys into Pyramid Lake and are on our way to Upper Ball Lake to plant the second group of thirteen hundred. Fortunately, it’s a cool day and the trails to Pyramid and Upper Ball Lakes are well maintained, which allows for quick progress and less time in the bag for the fish as the water warms and the oxygen is depleted.

Idaho has approximately three thousand alpine bodies of water that range in size from ponds to large lakes. The majority of northern Idaho’s alpine lakes were formed about ten thousand years ago when Ice Age glaciers receded. Ponds and lakes that speckle the high-elevation landscape throughout the state were born of melting ice and snow. Their outlet streams, which move rocks and vegetation as they tumble down steep slopes, often create waterfalls that are beautiful but are an impediment for fish trying to move upstream. These steep inclines and obstructions such as waterfalls prevented colonization of this new habitat. Consequently, most of our alpine lakes did not harbor fish before the 1920s.

Idaho Department of Fish & Game (IDFG) initiated a stocking program in that decade to provide additional angling opportunities for the fishing public. Back then, fingerling trout about an inch long were transported to the high mountain lakes in milk cans on pack mules. In the late 1930s, IDFG began to experiment with aerial stocking and in 1941, the first lake stocking by airplane took place in the Sawtooth Range. Helicopters were first used in 1958. From the air, the goal is to have the fish fall with the water, which makes one thousand fish per pound an optimal weight for stocking. Smaller fish may not fall with the water, and can be stunned or injured when they land. Larger fish create space problems in the aircraft. Stocking practices changed with the advent of the Wilderness Act in 1964. Only native species are now planted and the number of fish is based on the zooplankton population of the lake. In some locations, lakes continue to be stocked by airplane but mostly they’re planted with the use of motor vehicles, bicycles, pack strings, or by foot.

About thirteen hundred of the state’s alpine lakes are stocked on a rotating basis by IDFG and not all of them are as easy to get to as Pyramid and Upper Ball. My first time chaperoning tiny trout to their new home was a bit more of an adventure.

A storm building in the Selkirks. Mary Terra-Berns.

Morning view from Smith Ridge. Mary Terra-Berns.

Fingerlings in a bag. Mary Terra-Berns.

The fingerlings released. Mary Terra-Berns.

Taking a break at Pyramid Lake. Tony Berns.

The tiny fish are set free at Pyramid Lake. Tony Berns.

On this maiden stocking voyage in 2012, I accompanied Will Demien to Cutoff Lake. Will worked at the Cabinet Gorge Hatchery in Clark Fork, where the fingerlings are raised. Cutoff Lake is one of the most remote lakes in the Selkirk Mountains, just a few miles from the Canadian border. IDFG employees and a few volunteers from the public stock the lakes but rarely volunteer for Cutoff, mainly because there is no trail. It’s a great trip, though.

Will and I had an early start on this beautiful blue-sky day in early September. Getting there involves driving to the edge of the Canadian border on Westside Road to a hairpin curve where the road changes from Westside Road to Smith Creek Road and heads back south. After about six miles, we turned onto a smaller, rougher logging road and followed it to a wide spot at the end. From there we grabbed our gear, stowed the fingerlings in Will’s pack, and followed an old skid road to the Smith Ridge Trail.

The skinny and rarely used trail of about one mile crests Smith Ridge and heads to Cutoff Peak. In the early 1900s, the fire patrol boundary of long-time Forest Service employee Roy Hawks ended or cut off here, to be picked up by another patrol of the Bonners Ferry District. The creek and peak therefore were named Cutoff. At 6,844 feet, Cutoff Peak had a fire lookout tower and log cabin back then. The tower is gone, but the remains of the old cabin are still there.

Cutoff Peak was the opposite direction from where we were heading, which meant from here we were on our own, with no trail to follow. This was not a problem when we were following Smith Ridge but since neither one of us had been to Cutoff Lake, finding the right spot to drop down off the ridge to the lake was a bit of a mystery. We had some old notes from one of the previous hatchery trailblazers but they were, let’s just say, cryptic.

We picked a likely spot and dropped off the ridge. When I say dropped off, I mean dropped. Will, a foot and some inches taller and years younger than I, had an easy descent. So did Fiona, his chocolate lab. I found myself dangling, thankfully, from a sturdy branch of a well-placed shrub as my feet busily searched for solid ground. After about a minute or so, and assessing my landing options, I let go of the branch and alit on top of a smaller well-placed shrub where I was more closely connected to terra firma. Thankfully, Will was carrying the fish.

From here it was still a steep slope but at least we could sidehill down to something relatively horizontal, which ended up being a boulder field. Rock-hopping across this boulder field was a cakewalk compared to the section of rappelling via shrub. Fiona was not a fan of rock-hopping, so Will carried her to the edge of the boulder field.

Once we arrived at the lake and set our little charges in the water to acclimate, we sat down for some well-earned lunch, which was the critical cargo in my pack. Both of us were looking forward to a little population survey by fly rod and started pulling out our rods when off in the distance we heard what sounded like thunder. Sure enough, our blue-sky day was starting to cloud up. When we stepped out of the shade of the trees, we could see the clouds building.

The fingerlings had acclimated and had been freed of their plastic confines, so we quickly stowed our gear. It was not an option to return to the truck via our inbound route but we looked around and found a much easier and quicker way back up to the ridge. Once there, we were greeted with an amazing view that included seriously dark clouds building over the Canadian border and heading in our direction. We had prepared for the prospect of rain, but this storm looked like it was going to be a wicked one.

We put ourselves in high gear, and made our way across the ridge to the skinny trail and down to the truck with not a second to spare. The wind had picked up and was whipping the trees around and rain hammered the truck. Our smug “we win” haughtiness of beating the storm lasted a few minutes, until we realized we didn’t have a chainsaw. Now our concern was that the wind would start upending trees. We didn’t want to get stuck behind downed trees lying across the road. In the whoo of the wind, I could almost hear, “Ha-ha, I win.” We bumped our way down the switchbacks to the blacktop as quickly as we could on a logging road, breathed a sigh of relief, and then made our way back to town.

I still stock lakes but as a volunteer rather than a paid biologist, usually accompanied by Tony in places like Pyramid Lake and Upper Ball Lake. Most have nice trails but I would gladly trek back to Cutoff—so long as I tripled-checked the weather to make sure a blue-sky day would stay that way long enough to conduct a population survey with my fly rod.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Comments are closed.