No products in the cart.

Rosalie Sorrels

By Kitty Delorey Fleischman

Mellifluous. The word could have been coined especially to describe Rosalie Sorrels’ voice. Whether singing, or storytelling, the word fits. For days I’ve sought other, simpler words, but the search for vocabulary always dissolves to images. For Rosalie, speaking and singing are one. It’s how she communicates.

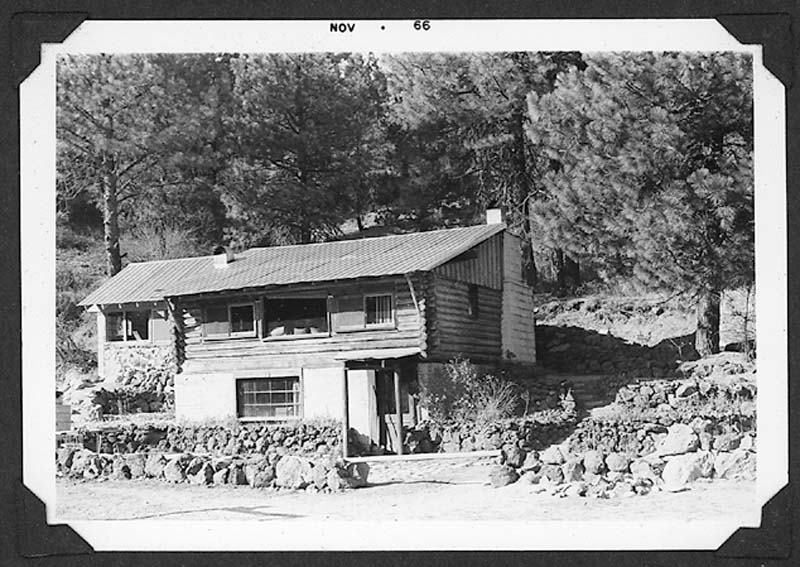

In her voice is the sound of Grimes Creek dancing over rocks and nudging flecks of gold along the course of its laughing waters. Then sometimes you’ll hear the gravel that lines the creek bed. You hear the trilling songs of birds that sail bright skies in her mountain sanctuary, and the shusshing sway of pine branches fluffed by breezes that sing to the cabin her father built by hand early in the last century. Sometimes you’ll catch a momentary glimpse of the sharp edges of rocks lining the canyon walls.

She came by it naturally as part of a well-read family of people who also loved to sing. As she talks, she switches from conversation to poetry to song in a smooth flow. In 1999 Idaho’s songbird also was chosen for a Circle of Excellence award from the National Storytelling Network.

For more than a half-century, Rosalie Sorrels has taken the sounds and stories of Idaho across the continent and beyond the seas. Jim Page, a folksinger from Whidby Island, Washington, once described Rosalie as “the most real person in folk music that I’ve ever met.” Now past her seventieth birthday, her outlook on life is both broader and narrower than it was when she was a younger woman. She has traveled extensively and has seen the world, yet the greatest treasures of her life are her family and her little handmade Grimes Creek cabin.

Her mother named the cabin Guerencia, which means “the place that holds your heart.” It’s a snug cabin with posters of her heroes on the ceiling so she can look up at them when she is in bed. The cabin’s walls are lined with books stacked layers deep on shelves, all of them read and all remembered.

Rosalie at a recent performance.

Rosalie's parents, Walter and Nancy Kelly Stringfellow.

Rosalie's handmade cabin on Grimes Creek.

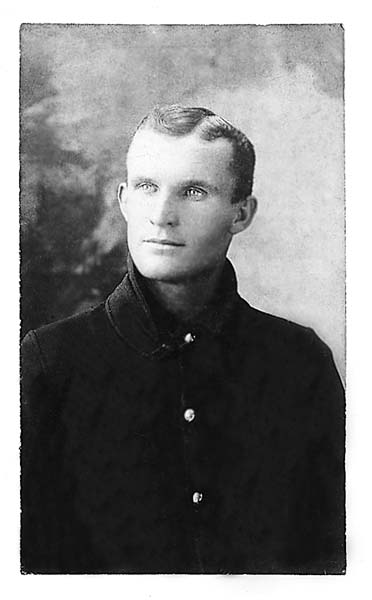

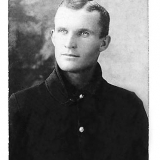

Rosalie's maternal grandfather, James Madison Kelly.

Rosalie during the Woodstock era.

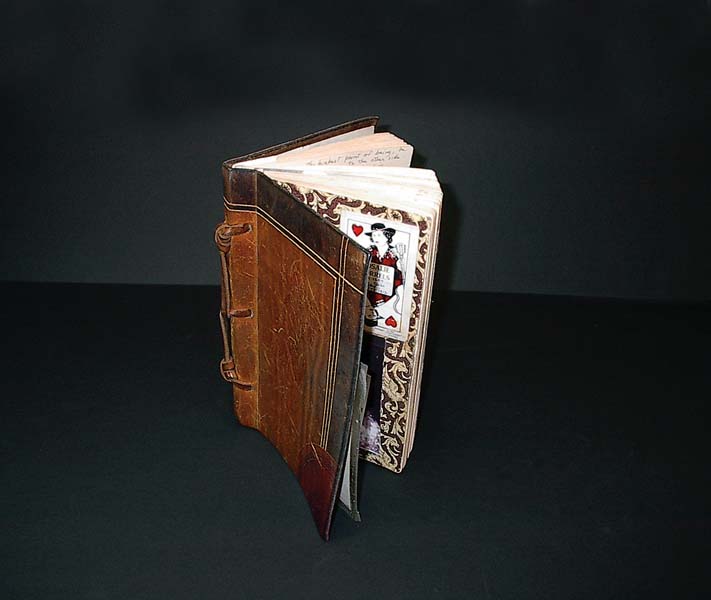

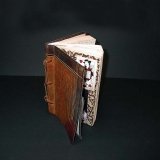

Rosalie's hand-bound journal filled with photos, thoughts and poetry.

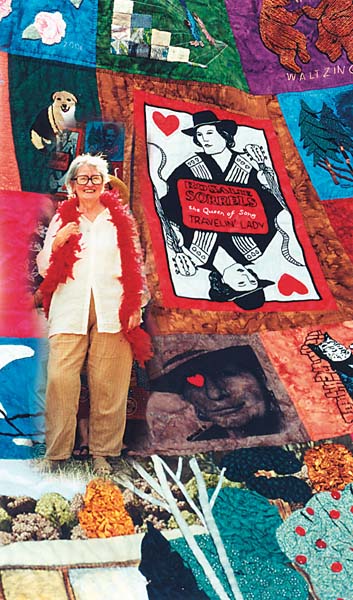

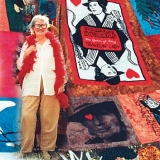

Rosalie in front of the quilt presented to her by the Boise Peace Quilters group.

As a youngster, Rosalie’s father gave her a dollar for each “chunk” of poetry she learned. She earned three dollars for learning Sir Walter Scott’s “Lady of the Lake.” When other youngsters were learning nursery rhymes, Rosalie learned to quote Shakespeare.

Rosalie Ann Stringfellow Sorrels’ parents met while they were going to school in Pocatello at what then was called “the southern branch of the University of Idaho.” She shows photos of the handsome young couple, whose looks compare favorably with a young Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. They were very much in love, Rosalie says, and over time grew to be the kind of couple who finished each other’s sentences until her father died on her parents’ fortieth wedding anniversary.

She was born at Boise’s St. Luke’s Hospital on June 24, 1933, ten years before her brother, Jim Stringfellow made his appearance. As a young child, Rosalie dressed in black because she liked it. She made up a group of imaginary friends, and she had some unusual pets—a snapping turtle, a small bat her father caught for her, and a horned toad.

Her family members were storytellers. Her father had a beautiful light, tenor voice, and he sang as he worked. Her mother managed The Book Shop in Boise for nearly two decades, teaching the people of Boise what to read. The family never had any money, she says, but “we were always making something out of nothing.” She grew up among books and songs, ideas and poetry. Now as she speaks, the names and thoughts of poets, writers, artists and musicians weave themselves lightly through her conversations.

Rosalie’s father was Walter Pendleton Stringfellow, the son of Rev. Robert Stringfellow, an Episcopalian preacher who came to Idaho when the state was in its infancy. While Rev. Stringfellow came with the idea of saving souls, Rosalie’s namesake and grandmother, Rosalie Cope Stringfellow, captured enduring photographic images of her handsome husband and stunning photos of wild, exquisite landscapes. For some time, she worked as a photographer for The Idaho Statesman.

Rosalie’s mother was Nancy Ann Kelly, whose own mother, Arabel Beaire Kelly, grew up in Twin Falls, as a devout Methodist. Nancy’s father was James Madison Kelly, “an Irishman and an atheist.” Rosalie remembers him as a handsome, slightly wicked man with a wild Irish tongue and a devilish sense of humor. “He even cursed at his horses in Shakespearean language.”

On her album “Report from Grimes Creek,” Rosalie retells a story her mother used to share about a day when Arabel was entertaining her gardening club. The ladies were discussing “ways to make dahlias grow as big as their granddaughters’ heads.” One of the ladies was a dear, old Scot with a lilting voice and a very large growth on her chin. It sprouted seven corkscrew curly hairs, Rosalie says, each a slightly different color. “No one would ever have mentioned it but my grandfather. He was wicked, and he couldn’t resist it.” One summer afternoon he came in from the fields, hot sweaty and covered with manure, looking for a cool glass of lemonade. He stood in the doorway of the parlor and regarded the ladies, and according to Rosalie, “In his best Macbethian voice, he said, ‘who are these so withered and so wild, who look not of this earth, and yet are on it? They must be women, but their beards forbid it to be such.’

“My mother said my grandmother cried for hours over the incident, finally sobbing, ‘Oh God…if only I could have told them that he was drunk. But everybody knows Jim never touches a drop.’”

Rosalie says it may have been her deep love for her handsome, roguish grandfather that has made it so hard to find the right man in her own life. He was her ideal, and she’s never found anyone quite like him.

Five generations of Rosalie’s family have lived and worked in Idaho, but as a young woman, she wanted to be off to see the world. At nineteen she left Idaho. Rosalie married Jim Sorrels and they lived in Utah. She became the mother of five. Her husband beat her and her children so, after fourteen years of marriage, she took her children and left. She took to the road and followed her true love, music. She began singing in clubs, and became known as an entertainer. She sang for her supper, and told stories to her audiences.

The world stage has provided an interesting life for the little girl who grew up “Way out in Idaho.” She has met and entertained most of the members of the Beat Generation. They’ve stayed at her homes. She’s cooked for them, and she’s sung with them. Along the way, Rosalie’s friends have included Studs Terkel, Pete Seeger, Hunter S. Thompson, and…well, perhaps it would be easier to list those from that generation that she did not know. Beyond her own generation, she’s been a mentor to those in the generations that have followed.

Although she says she’s never earned more than twenty thousand dollars a year in her life, Rosalie has performed in every major musical festival on the North American continent (and beyond) in the past half century. She sang at Newport in 1966 and at Woodstock in 1969. On the Isle of Wight in 1972 she sang early in the day to a crowd estimated at eighty thousand and she received a standing ovation. “I was scheduled to sing early in the day because back then almost nobody there knew who I was. Later in the day there were two hundred fifty thousand people there. By that time there were riots going on in the crowd and Kris Kristofferson got booed off the stage.”

She loves to entertain at her cabin, and she cooked for a crowd of more than two hundred that came for her seventieth birthday party. She enjoys cooking, she says with a look that begs the question: doesn’t everyone?

Stories flow as Rosalie fingers the well-worn pages of a handmade leather volume plumped with photos of friends and family, dried flowers, airline ticket stubs, and mementos. Its pages are filled with hand-written lines of poetry and thoughts. They’ve been saved over the years, and are shared on stage as she spins her web of stories and songs.

While she sings many songs that have been written by other performers, most of her songs are her own. Even when she sings music written by others, you have a feeling that it has been chosen because it speaks to her heart. Everything Rosalie sings sounds like it came straight from her heart. Many of her songs, many of her albums talk about her heart.

In the song, “Borderline Heart,” from the album by the same name, Rosalie sings:

Rosalie’s songs are often deeply personal. One of her early songs, “Traveling Lady,” tells of her divorce and heading out on the road. When she sings the blues, you can tell she’s done some “hard livin’” herself. She says the road is a tough place for a woman on her own. Also from the Borderline Heart album, the song “Hitchhiker in the Rain” tells the story of the 1976 suicide of David, her elder son. David, she said, often told her it would damage his hitchhiking karma if she didn’t pick people up when she saw them hitching rides. Even after his death, Rosalie continued to pick up hitchhikers despite warnings about the dangers. She told friends she always picked up the ones carrying guitars until someone pointed out that Charles Manson had a guitar. She then stopped picking up hitchhikers.

Memories flow like the songs as Rosalie talks. She has a new CD scheduled for its street release on April 6. It was recorded at a sold-out performance at the Sanders Theatre on the Harvard campus last year. Entitled My Last Go Round, Rosalie says it is her favorite album from among the twenty-four she has made. Recorded live, she says a young engineer has gone through and enhanced the music so it sounds exactly the way she heard it as she stood on the stage the night it was recorded. And more importantly, she says, she performed the concert with many of her old friends.

The last go round, she says, is an old rodeo term used to describe the final (and best) performances, after the crowd has gone home. She’s celebrating it as her “farewell to the road” album.

Rosalie is a virtual encyclopedia of musicology. She collects songs of all kinds. In addition to all of her songs, she also has written three books, including a lovely softbound edition of songs and stories entitled, “Way Out in Idaho,” which was compiled by her and edited with her friend, Jean Terra. It was published by the Idaho Commission on the Arts in 1991 for the state’s centennial celebration, and includes folksongs, poems, legends, and recipes representing the rich cultural tapestry of the state.

A recent visit to Rosalie’s cabin finds her sorting through fragments of her life, boxing things up and sending them off to the University of California at Santa Cruz. The university is in the process of establishing the Rosalie Sorrels Archive, a permanent collection highlighting her life. Why a California school and not one of Idaho’s schools? Although she was presented with an honorary doctorate by the University of Idaho a few years ago, apparently nobody in Idaho has asked for her memorabilia.

“People in Idaho think of me as a nice old lady who collects Mormon songs. People in California know who I am. They consider me a voice of the ‘Beat Generation.’” On Valentine’s Day in 2003, she gave a free concert on the UCSC campus, and at that time she presented the school with the beautiful quilt she was given by the Boise Peace Quilt Project.

A few years ago, after taking part in a class action suit against Green Linnet, which had owned the rights to her music, Rosalie regained control over her songs and started her own recording label, “Way Out West in Idaho.” Her first CD produced under her own label was entitled “Learned by Livin’ Sung by Heart.” The title says it all.

Rosalie has outlived a brain aneurysm in 1988 and she beat breast cancer in 1998.

Speaking of her life, Rosalie quotes, “I won’t know what I’m weaving until I’ve got it made.” Nonetheless, she has everything she wants in life: “I have my handmade cabin, children who like me, and the respect of other performers.”

With seventy years of living and nearly fifty years of performing under her belt, Rosalie’s voice is still as fluid and flexible as it was on her earliest recordings. It is still a mother’s lullaby, mellow and smooth as honey when the song calls for it. It still twangs like barbed wire when tested. It still has a rock hard edge when the blues demand it.

She’s ready for the last go round.

Comments are closed.