No products in the cart.

The Big Brass

At a Backcountry School

By Katherine Wonn Harris

Following is an excerpt from Topping Out, the late author’s account of teaching children in 1916 in the remote Salmon River country west of White Bird, which she did for seven years. Originally appearing in 1971, the book’s second edition was published this year by the author’s niece, Marilyn Allen. Its illustrations are by Chief Joseph’s granddaughter, Bonnie D. Joseph. Some names of places and people have been changed. The “tragedy of the blackboard” in this story refers to a goat eating the school’s canvas blackboard.

Travelers along the Rim Trail averaged two or three a day, usually lone horsemen and occasional pack outfits, the long mule trains of the forestry service being the most frequently seen. Passing by our door, brief amenities were usually exchanged. The olive-green garb and stiff-brimmed felts distinguished the men of the Forest Service, whose role in the early days of their department’s jurisdiction was far from a happy one. Preaching the doctrine of conservation to a people reared to exploit resources resulted in open hostility and, often, vindictive behavior by those whose cooperation with a planned economy was sought.

The native rancher, accustomed to unrestricted use of public grazing, accepted with ill grace the allotting of privileges on the national forest reserve. The written applications, together with oral questions put by the resident ranger, were fiercely resented, for these people were reticent about their personal affairs, their possessions, and their past activities and future plans. Those who asked such questions were unpopular, but the ranger had no choice.

Methods of overgrazing had already destroyed wide areas of the nutritious bunch grass, which was replaced with stands of ragged cheat, worthless as forage. Allowing more cattle or sheep in a given area than the grass could support with any hope of survival was sternly dealt with by the forestry men. It was obvious that the stockmen’s estimate of how many head an area would support was much higher than the rangers’ figure. That argument continues to this day [1970s].

Regular salting at accustomed spots was advocated as a means of keeping stock within their given range. The salvage of springs through simple protective measures, the killing of game only in season—all were rules difficult to enforce, for care of the native forage and wildlife came hard to a people accustomed to employing savage measures against a savage land.

The rangers frequently found it easier to deal with the big cattlemen or sheepmen. To them, use of the high summer range was vital. They were, therefore, more amenable to pressures and could be forced to comply with regulations through threat that grazing permits would not be renewed. The scores of small-fry stockmen and homesteaders whose negligible herds could “get by” multiplied the rangers’ problems many times over. Acting on the privilege of taking two hundred dollars’ worth of timber from the reserve for buildings or improvements, they frequently cut the trees and left them where they fell, thus scarring their ranger’s district and bringing down upon him the wrath of his supervisor for allowing fire hazards to exist.

The killing of deer out of season was also a practice that led to endless altercations, as was the manufacture of various vitriolic messes of moonshine, which came mainly from the homesteaders and found eager purchasers throughout the canyon country. Although the rangers stoutly denied their interest or jurisdiction in the concoction of these unlawful brews, they were nonetheless blamed for having informed the law when a raid was made. This occurrence was so infrequent that it set the whole country agog, for few revenue men possessed the temerity to invade the canyon country, and those who did nearly always found themselves “jobbed” [betrayed]. News of their coming was relayed ahead in sufficient time for the embryo distiller to conceal evidence of his activity.

Some of the men reared in the country found places in the forest service as rangers and packers, and they were tolerated for their understanding of ways and conditions. But the “schooled” ranger or supervisor trained by precept for his job had a rough time of it. He was simply unacceptable, for the natives particularly resented those whom they figured had “learned it in books” and were constantly alerted to catch them in the promotion of impractical ideas.

Such a man was Anthony Stettin, who scaled to greater heights in authority then any department representative who had ever invaded the canyon districts. His spot visitations throughout the West that summer were designed to obtain firsthand knowledge for the edification of the department, and he was out to glean his knowledge the hard way. Unheralded he came, clothed in the regal authority of the federal government, correctly uniformed, and sitting his saddle with the stiff misery of the uninitiated. The first time he passed our camp with Jack Downey, the resident ranger, he accorded us little more than a brief nod accompanied by an incredulous stare at our scarecrow camp and ragged equipment. Ranger Downey paused, as was his habit, for an agreeable word, but his companion rode straight ahead with no backward glance.

Katherine Wonn Harris when she was in her seventies. Courtesy Marilyn Allen.

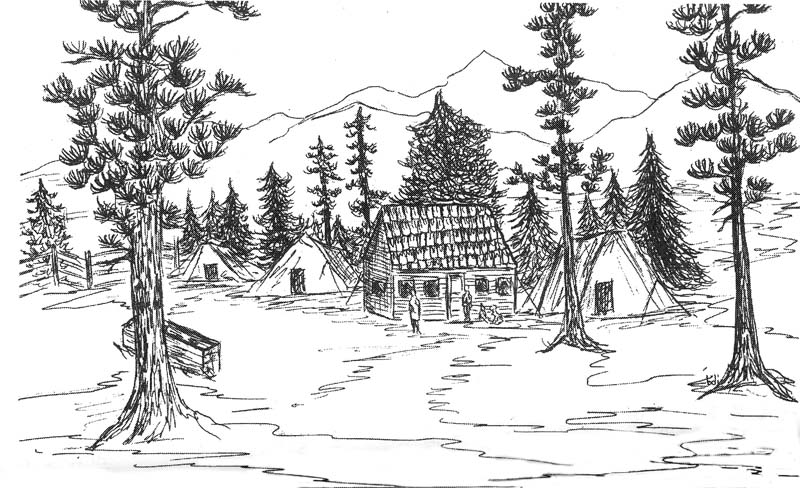

The backcountry schoolhouse. Illustration by Bonnie D. Joseph.

“A government big-bug,” Downey confided. There was awe in his voice and pride in his bearing.

I watched with pleasurable interest as Downey rode in the company of so great a person. Not so the children. Their hostile stares followed the pair as they disappeared around the turn.

“A high mucky-muck, I betcha,” commented Young Jim. “Gar, did you see the polish on his boots?” exclaimed Clem. “Tony-Toes,” shouted Bib. “That’s what he is. Old Tony-Toes!”

“Those smart-aleck forestry men,” observed Maryadee with venom. “Always snooping around. And two years back, one of them took our teacher and never brought her back, that’s what!”

“Maryadee,” I said severely, “no one forced her to go. She went willingly. And we’ll talk no more of it.”

I had heard the teacher-napping tale with embellishments from Mrs. Mac during my first weekend in the MacDeen’s camp; the story was intended certainly to impress me with the horrible example set by a predecessor.

“He was a reckless young rake who packed that summer for the forest service,” Mrs. Mac had said. “Somehow him and this teacher managed to see a good bit of each other right from the start. She’d been here hardly a month mind you, when he came along one morning packing back to Homestead. Had an extra saddle horse. Took her and her things, and off they rode. Never saw hide nor hair of either one again, for you can be sure that caper finished him with the forest service. And that teacher! Left those poor children alone at the camp. A fine thing.”

Knowing the ability of the “poor children” to shift for themselves, I was only passively horrified by the tale. “Must have been quite a blow to Mr. MacDeen.” I envisioned with pleasure his discomfiture at the escape of one of his catches.

“Mac was fit to be tied,” she stated. “Swore he’d do something about it, but he never did. Couldn’t get another teacher that summer either.”

“Serves him right,” I said recklessly. “Getting teachers in here under false pretenses!”

Mrs. Mac fixed me with a stern eye. “No teacher has to stay here if she doesn’t want to, but we do think we might be told of her intentions.”

“Well, I’m staying,” I said. “To the bitter end.”

Returning alone the next week from the forestry office at Joseph, the “Big Brass” rode past the school camp shortly before supper. He stopped, smiled, and raised his stiff felt.

His face was lined with fatigue; the close-cropped mustache looked a little ragged, and he could have done with a haircut. The formerly polished boots were sadly scuffed, and dust lay heavy upon them.

“I didn’t realize when I passed last week with Downey that this was a school. It has none of the ordinary signs. Most unusual. I want to commend you on carrying out such an assignment. I shall mention it in my department reports.”

“Yes,” I said, striving to match his impeccable diction, “ the school is on forest reserve land, I believe.”

“A most worthy use,” he stated pedantically.

“Mr. Downey is not with you?” I felt an insatiable curiosity as to why this greenest of all greenhorns had been left unguarded on this of all hazardous trails.

“Downey has other duties than escorting me about. There is much—much to be done here,” said the Big Brass. I suspected that Downey had received considerable instruction straight from the book, and I felt sorry for him. The man’s lot was already hard enough.

The children gathered beside me in a tight knot. Silently they observed the Big Brass with bright, suspicious eyes.

“You’re not intending to make Homestead tonight surely,” I said, noting the fatigue of man and horse.

“Only to our temporary camp a little past Pan Creek.”

“That’s still nearly two hours from here,” I remarked.

“So strange, measuring distance by hours. But after this trip, it is quite understandable.” He shifted slightly in the saddle, but only his eyes mirrored the pain of movement.

“Would you have supper with us?” I inquired impulsively. “It is nearly ready for the table.”

“I would with pleasure.”

There was no hesitancy in the acceptance.

Painfully he removed himself from the saddle.

Hostile silence and no movement from the group at my side.

“Jim,” I said sharply, disconcerted at their ghoulish behavior, “will you care for the horse?”

Reluctantly Young Jim slouched forward, loosed the cinch, and led the animal up to the water trough.

It was a strange meal, the Big Brass and I carrying the total load of conversation. I tried by every effort known to me to induce these children to show some friendliness, but all ate silently, eyes on plates.

“Such well-mannered young people,” the Big Brass finally remarked. “And this young lady,” indicating Essie who sat at his right, “reminds me of my own little daughter in Washington. Not at all like me, understand, but a beautiful blond like her mother.”

At this, Essie wriggled, and her taut braids vibrated. It was probably the first compliment ever accorded the plain child. Suddenly she flashed our guest one of her rare smiles, and something certainly akin to loveliness transformed her face. That broke the ice, and the tension around the table lessened.

After supper, we all trooped to the schoolhouse for an inspection requested by the Big Brass. In the fading daylight, the room’s scant equipment, its pitiful bareness, was sharply accented. The tragedy of the blackboard was related by Essie, who stuck to the big man’s side like a small, nondescript burr.

“Incredible,” said the Brass.

To me, he remarked in a low tone, “I have never seen a schoolroom—any room—with so little. How do you manage?”

“We do all right,” I said. “We get the job done.”

He eyed me thoughtfully. “I’m sure you do, but still …”

As Young Jim cinched his saddle, I covertly suggested that he and Clem get their horses and escort the Big Brass along his way. “At least through that mean Pan Creek Canyon,” I whispered. “No telling what may happen to him alone, and it’s getting dark.”

“No big loss if something did happen.” Young Jim’s tone was cold. “Besides, his horse will get him there.”

“Offer to anyway,” I insisted sharply.

But the Big Brass would have none of it. He was quite capable of taking care of himself, he said, and so he rode off, stiff and uncompromising in his saddle.

Ten days later, a forest service packer stopped and unloaded at the school a wondrous cargo.

“Orders from the boss to handle with care,” he said, “and an installation job for me.”

Dismantled and packed in four sections was a blackboard that would have added glamour to the walls of any city schoolroom. There were also white and colored chalk and a dozen entrancing books of history, travel, and adventure.

“We’d ought to write him a letter,” said Young Jim.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only