No products in the cart.

The Making of Psychiana Man

A Note on the Sources

By Brandon R. Schrand

The following excerpt from Brandon Schrand’s introduction to his new book Psychiana Man: A Mail-Order Prophet, His Followers, and the Power of Belief in Hard Times, is printed here with permission from Washington State University Press. In it, the author describes how he came upon an Idaho mail-order “money-back-guarantee” religion that flourished during the Great Depression, the historical materials he examined, and the method behind his years of research.

It was by complete chance that I learned about Frank Bruce Robinson and Psychiana. In 2014, I had decided to write a letter to the editor of my local paper, the Moscow-Pullman Daily News, about a neighborhood zoning issue. Because I wanted my letter to provide some historical context, I consulted a local history book, Moscow (Images of America series) by Julie Monroe. It was in her volume that I first happened upon the photos and brief description about a strange religion and the man who started it.

The story was so bizarre and baffling that it seemed like bad fiction. But it was not. It was all too real. The more I looked into it, the more fascinated I became. My interest in Psychiana did not hang from a religious or ecumenical hook, however. I am not a religious man, and my curiosity seldom runs in that direction. Instead, it was the human perspective that had hooked my interest. The question I asked then, and that I asked throughout the writing of this book, was simple and endlessly (at least to me) profound: why do people believe what they believe? Especially if something seems by all accounts to be specious or suspect, and even if facts fly in the face of the thing or person believed in, why do people hold fast to their convictions?

Initially, I thought I might write an essay about Psychiana, or a magazine piece about Robinson and his religion as a way of addressing some of these ongoing questions. But in a matter of days, I discovered that the story was far too big for an essay or article. It demanded the space of a book.

Cover of the new book. Washington State University Press.

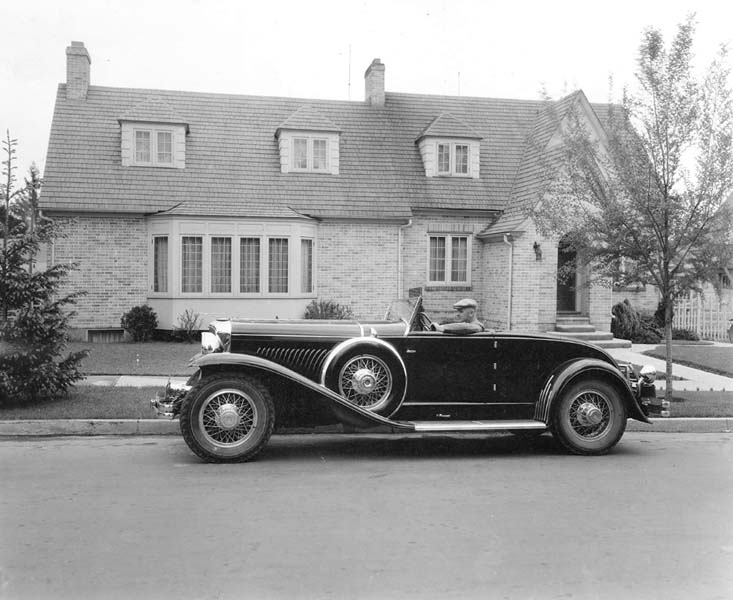

Frank B. Robinson in his Duesenberg. Latah County Historical Society.

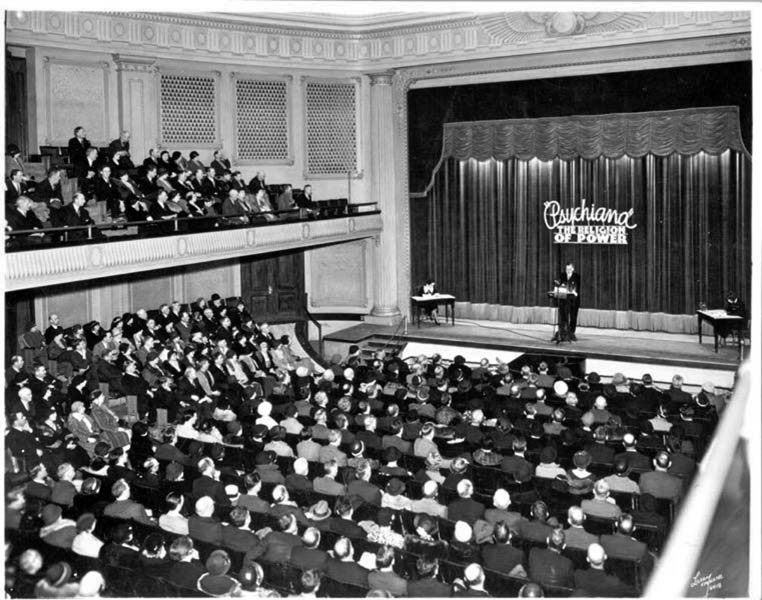

Robinson addresses a crowd. Washington State University Press.

* * * * *

Officially, I had two autobiographies to consult in writing this book: The Life Story of Frank B. Robinson (Written By Himself) and The Strange Autobiography of Frank B. Robinson. The titles alone, however, are enough to put attentive researchers on guard. As artifacts of record, neither of these works is wholly reliable. Their veracity has less to do with the vagaries of human memory and more to do with the calculations of a gifted ad-man. Still, they are valuable to the researcher for what they do not say as much as for what they do; for what they purport as much as for what they reveal. That said, their internal contradictions, obfuscations, omissions, and prevarications presented real and substantive challenges that demanded constant corroboration. Moreover, the entire narrative thrust of Psychiana is so inextricably tied to Frank Robinson‘s life story that all of his written work including the lessons, books, magazines, newsletters, radio programs, broadsides, and advertisements are autobiographical in nature, making the task of writing accurately about his life challenging in the extreme.

Fortunately, I was not the first person who tried to corroborate Robinson‘s life story. His son, Alfred Robinson, wrote A Family Trilogy, an unpublished and thoroughly researched genealogical history and exploration of his father‘s history and movement. Each of the three manuscript volumes contains scores of documents and records, along with the narrative of his journey in tracking down these sources. Alfred had donated several bound photocopies to the Latah County Historical Society. I would not have been able to write this book had it not been for Alfred Robinson‘s steadfast work.

Indeed, one aspect that most aptly characterizes the Latah Historical Society’s Frank Robinson materials is the intimacy of the documents. Their photographs, trove of personal correspondence, financial statements, and family records reveal an unflinching and often shockingly candid portrait of Frank B. Robinson that is not portrayed anywhere else in his voluminous output of writing. The society’s records on Robinson‘s federal trial and legal troubles were invaluable as I pieced together how his alleged criminal acts were always linked to his origin story. Of particular value, too, were the society’s oral histories by Sam Schrager, who in the 1970s interviewed a number of Psychiana employees and individuals who were otherwise familiar with Robinson, his family, and his movement.

The Frank Bruce Robinson Papers at the University of Idaho, on the other hand, are less intimate, perhaps, but are enormously substantive in their scope of operational and organizational materials, including advertisements, publications, flyers, propaganda, books, monographs, promos, audio recordings, company audits, news clippings, draft manuscripts, office memoranda, scrapbooks, telegrams and cables, legal documents, and of course the student letters themselves.

I had spent about a week poring over a fraction of the student correspondence when it became clear to me that I wanted my book to be as much about them and their lives as it would be about Frank Robinson and Psychiana. Taken together, these letters served as a mirror that reflected the perceptions and realities of Psychiana, but also the perceptions and realities of daily life in the Great Depression across America and abroad. Ultimately, I wanted to create a kind of national composite diary, a cross-section of private lives bearing witness to the unraveling of a nation in real time. Little did I realize just how long it would take to read my way through all the correspondence, let alone how difficult it would be to tease out which student letters would best serve the narrative I wanted to write.

Ultimately, I devised four criteria that helped me decide which letters might be included over others. The first criterion was that the student letter had to illuminate some aspect, however small, of Psychiana or Robinson himself. This could entail anything from the mailing process to the exchange of money, lessons, brochures, or other materials. It could also include the tone or tenor of Robinson‘s responses to students (or lack of response), or the difference between a genuinely personal reply and a form letter. It entailed, too, the degree to which Robinson became reliant on assistants to answer the deluge of student correspondence. The second criterion was that the letters had to address the concept of belief either implicitly or explicitly. Third, the student had to be “storyable.” In other words, I had to find enough of a paper trail on the individual student—vital records, census data, newspaper articles, maps, city directories, along with information on his or her community—to create a serviceable vignette that would offer a window not only into that part of the world at that time, but also into why that average person might find solace in Psychiana.

The final criterion was that the letters had to reflect not just the diversity of Psychiana membership, but more generally the religion’s broad appeal during hard times, showing that it was far more mainstream than fringe. It was important to me that readers understood that Psychiana members were not all cut from the same cloth. On the contrary. They ranged from the highly literate and even literary to the barely literate; from atheists to ordained ministers; from the affluent to the destitute; and from cops to criminals. And perhaps most notably, because Psychiana was a mail-based religion, it was truly color-blind, making its membership strikingly racially diverse and all-inclusive for the time.

In the years I spent digging through this trove of correspondence, I expected to read letters from disillusioned students writing in to voice their grievances and demanding their money back, per Robinson‘s vaunted policy. I kept expecting to find a whistle-blower in the reams of pages, some clarion call denouncing the entire operation. But if such a recalcitrant letter existed, it was not kept or has been lost. What I did find, however, was far more telling. The handful of students who did grumble or grouse about the cost of lessons, form-letter responses, mailing delays, and the like, still remained faithful—ardently so. An important text I kept on my desk during the writing of this book was Benjamin Roth‘s Great Depression Diary, edited by James Ledbetter and Daniel B. Roth. So much of what I wanted to capture in this book was the individual‘s voice trying to make sense of the world in incredibly difficult times. Not only did I find that in Roth‘s diary, but I also found a voice I could use to compare and contrast with those of Psychiana students, often on the same day.

Likewise, it was imperative that I immersed myself in the history of the Great Depression. One of the go-to texts I also kept on my desk was Robert S. McElvaine‘s The Great Depression: America 1929-1941. Immensely readable, McElvaine‘s text was instrumental to my work, as it charted the political, social, and economic shifts that tracked parallel to Robinson‘s establishment of Psychiana and its subsequent success. It was incredibly important too in establishing a broader context for what some of the Psychiana students were going through personally, particularly when it came to labor strikes, Relief Rolls, and the fluctuating prices for everyday goods like meat, coal, and wheat.

Morris Dickstein‘s Dancing in the Dark: A Cultural History of the Great Depression was also helpful, especially as I tried to peer into the daily lives of Psychiana students. When I wanted to know what songs or movies were popular (and why), or what books people were reading, Dickstein‘s sweeping work was the one I returned to time and again.

As the Great Depression sowed daily uncertainty in America and worldwide, people began turning to self-help books, lessons, and organizations. (It is not entirely coincidental, for instance, that Alcoholics Anonymous was founded in this period.) Indeed, if any one era can be credited for the rise of self-help, it may have been the Great Depression, a period in which people began to distrust the very institutions they had previously relied on: banks, government agencies, even church. To further understand this cultural shift, I turned to Mild McGee‘s inestimable Self-Help, Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life. McGee shows how movements like New Thought (a “parent” philosophy of Psychiana), founded in the nineteenth century, flourished in the Great Depression. She further points to self-help as not just a byproduct of the Depression-era zeitgeist, but also as an American capitalistic phenomenon. It was her text that provided me with a theoretical framework into which I could ably situate Psychiana.

Her work also alerted me to a number of other writers and thinkers of the period who were working along similar lines as Frank Robinson, many of whom directly influenced him. It was important that I familiarize myself with figures such as Robert Collier (Secret of the Ages); Charles Haanel (The Master Key System); Bruce Barton (The Man Nobody Knows); Ernest Holmes (The Science of Mind); and of course Dale Carnegie (How to Win Friends and Influence People). The sheer proliferation of these writers and works cropping up out of the Great Depression was, to my thinking, markedly suggestive of deeper cultural moods and temperaments of that particular era when people needed, and sought out, advice.

But if Psychiana came of age in the Great Depression, it also fledged concurrently with the steady rise of fascism worldwide. Because Robinson so explicitly lassoed his movement to global news and trends for what were clearly reasons of currency and relevancy, Psychiana became as intertwined with the rise of World War II as it was with the Depression itself. Tracking Robinson‘s movement in the newspapers became a master class in Hitler‘s rise to power and the world‘s ineffectual and tacit response to his and other totalitarian regimes. For help in capturing the simmering mood of this seminal moment in global history, I turned to Erik Larson’s In the Garden of Beasts. By no means an academic or definitive history of Hitler’s ascension, Larson’s book nonetheless provides a chilling window into the daily indifference and acquiescence ordinary people seemed to show toward the march of authoritarianism. And because my book was so grounded in the daily perceptions of ordinary people living in extraordinary times, In the Garden of Beasts was extremely useful in identifying the machinations of that slow burn.

Of course, there was no better body of work to study than Frank Robinson‘s own oeuvre. That he was prolific goes without saying. However, much of his work—particularly his later writings—was largely derivative, recycled from previous publications. Robinson‘s chief talent did not reside in generating original content, but in repackaging extant content in original ways.

That said, Robinson‘s most original and convincing ideas were laid out in his first set of Psychiana Lessons and in his debut book, The God Nobody Knows. In many ways his most cogent work, The God Nobody Knows promulgates the fundamentals on which Psychiana would stand for decades to come: a wholesale disavowal of conventional religion, and the Bible specifically; an embrace for a more universal God power, rather than a God entity; and a reliance on daily affirmations and self-empowerment.

This content is available for purchase. Please select from available options.

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Register & Purchase Purchase Only

Comments are closed.